In 1944, the Allied forces defeated the Japanese in the southern Philippines. That done, they began landing Allied troops on the central Philippine island of Leyte, leaving only a few destroyers behind to protect the landing. But it was a trap, so all seemed lost till an Amerindian captain decided to go kamikaze on the Japanese.

After the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, they continued their spree in the South Pacific. They captured the Philippines (then US territory) and other nations until they acquired Papua New Guinea at Australia’s doorstep.

Since America’s original focus was on the European theater, its attitude toward the South Pacific had been one of Japanese containment. This changed in 1943. By June, they captured some of the Solomon Islands, isolated a major Japanese base at Rabaul, and secured their access to Australia and New Zealand.

That done, US and Australian forces began capturing the other islands till they reached the Philippines in mid-1944. They first took the southernmost island of Mindanao, then made their way north. But first they had to get past the central island of Leyte, which they reached on the morning of October 23.

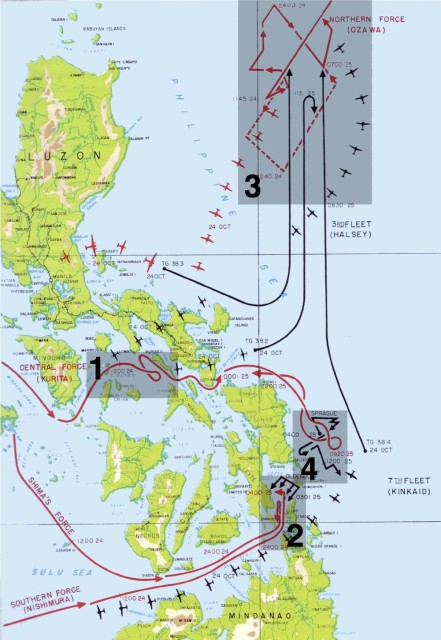

But then their submarines detected a Japanese fleet coming in from the South China Sea. Fleet Admiral William Frederick Halsey, Jr., was also known as the “Bull” because his policy was simple: sink as many Japs as possible. And that’s exactly what he did, destroying the Center Force under Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita. Or so he thought.

On October 24, 150,000 American troops began landing on Leyte, but as they were doing that, they received intel of more Japanese carrier-battleships heading their way. Instead of staying to protect the landing, the Bull went after the Japanese, leaving behind only a few small escorts and destroyers.

Though taking on some damage, Kurita wasn’t headed back to Japan for repairs. He had simply turned around and was headed back to Leyte. To make sure he made it, the Japanese Northern Force sent out several carriers as decoys to lure the Bull’s 3rd Fleet away from where the real action was about to happen.

Only the Philippines and Taiwan stood between the Allied forces and the Japanese home islands. The Japanese High Command couldn’t possibly let go of the Philippines, so the Americans had to be stopped at Leyte. If they got passed that island, then Luzon (the main island where the bulk of Japan’s occupying forces were) was next.

Off Leyte, Task Unit 77.4.3 (Taffy 3) was under the command of Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague. It only had a few destroyers, slow destroyer escorts, and escort aircraft carriers, most armed with 5 inch 38 caliber guns and torpedoes. Among these was the USS Johnston (DD-557), a small Fletcher-class destroyer under the command of Lieutenant Commander Ernest E. Evans.

Evans was part Cherokee and part Creek, and had seen combat at the Battle of the Java Sea. He served as a junior officer aboard the USS Alden which had to retreat from battle, something he had never forgotten. When given command of the Johnston, he announced that he intended to get into harm’s way, so if any of his crew didn’t like it, they could get off.

At 6:45 AM on October 25, Ensign Bill Brooks was doing a routine aerial patrol when he had a virtual heart attack. Bearing down on the landing team was Kurita’s fleet with four battleships, eight cruisers, and 11 destroyers. The only thing protecting the landing force were Taffy 3’s 16 small unarmored escort carriers and some destroyer escorts. Completely outgunned, the Americans were sitting ducks.

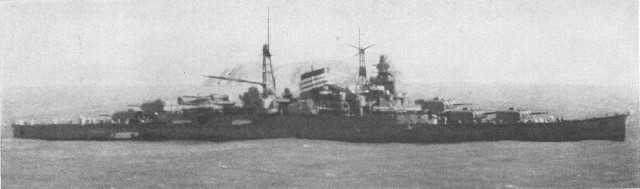

The USS Johnston was the closest to the oncoming Japanese fleet, so Evans ordered his men to attack. Measuring 376’ 6” in length, it was armed with only 5-inch guns and 10X21-inch torpedoes. Its target? The Kumano cruiser, stretching 661’ 5” in length and armed with five triple 6.1-inch dual purpose guns and Type 93 torpedoes. But Evans intended to keep his vow about getting in harm’s way.

Almost half the size of the Kumano, the Johnston charged ahead in a zigzag pattern. It emitted screening clouds of smoke, careful not to lay it on too thick to avoid giving away its position. Evans wanted to sink the cruiser with his torpedoes, but they only had a range of five miles.

To buy time, Senior Gunnery Officer Robert Hagan opened fire when they were 10 miles away. Wherever he pointed his telescopic sight, all five guns would follow by using the analogue fire control systems to automatically compensate for lead angle, azimuth, and ship’s roll.

Knowing his rounds couldn’t penetrate the Kumano’s hull, Hagan carefully aimed at the bridge, blasting it with a 200-round bombardment that rocked the cruiser with some 40 hits. The other destroyers took Evans’ lead, while planes took to the air to harass the Japanese.

The Johnston took on heavy fire, but managed to fire its first torpedoes at five miles. It hit the Kumano, but return fire blasted the Johnston’s bridge, burning Evans and killing other crew members. At 7:25 Lieutenant JG William Gallagher fired the Mark 13, America’s first aerial torpedo from his plane onto the Kumano, which sank at 7:27. To this day, no one’s sure if Gallagher or Evans was responsible for the sinking. Possibly both.

The Suzuya cruiser tried to rescue the survivors of the Kumano, but Evans sank the Suzuya with another volley of torpedoes. The Yamato scored three direct hits on the Johnston, but despite heavy damage and a high casualty rate, it continued fighting. By 9:45, however, the Johnston was a complete wreck, and Evans gave the order to abandon ship.

It sank at 10:10 AM, and of the 327 men aboard, only 141 survived.

Though they outgunned the Americans, the Japanese were so harassed by US destroyers and planes that they couldn’t coordinate their attacks and lost far more ships and men than did the Americans. With so many of their ships destroyed at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the Japanese resorted to more kamikaze attacks from ground bases, most of which missed their targets at sea.

As for Evans, he went down with his ship and his body was never found, but he was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor, having saved the invasion fleet from near certain destruction. He is remembered on the tablets of the missing on the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial.