Stinky and the Emergency Part 1

Wouldn’t it have been a terrible thing if, in the middle of WW2, the people responsible for training and equipping the US Army’s armored force were taken prisoner? Well, they were.

There are probably going to be a couple of interesting surprises for you in this article. One of the less interesting surprises is that there was a B-17 named “Stinky.” Stinky was a B-17E. 41-9045, to be more specific. The aircraft was lost as a result of an in-flight emergency. In charge at the time was Cpt Thomas Hulings.

You’re probably wondering why I’m writing about a B-17 on the Tanks portal. Bear with me.

Ireland had a fairly lengthy disagreement with its nearest neighbor, the UK, which was only settled less than 20 years before WWII. That disagreement was only finally resolved after a rather nasty civil war barely fifteen years prior, and de facto independence had come only a couple of years in the past. Despite the long-term ties between Ireland and the UK, given this recent turbulent history and the large death toll of Irishmen the last time the UK got involved in Continental Europe, it was fairly difficult for the Irish government to climb onto the United Nations bandwagon. That said, Ireland certainly leaned more towards the Allies than the Axis, so if an alliance was out of the question, neutrality was going to be the next-best-thing.

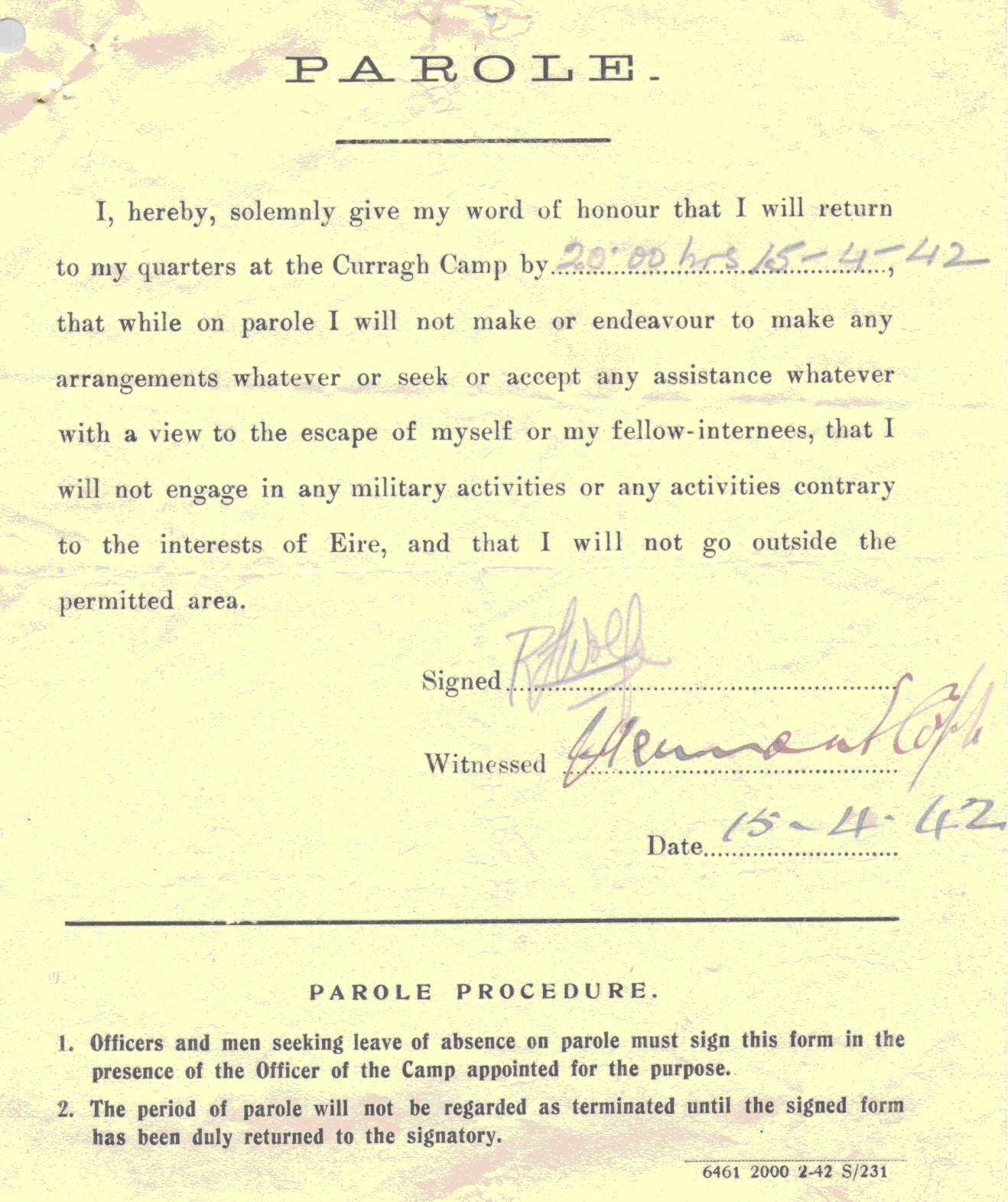

As part of this neutrality, Eire started a policy of internment. Any combatant from any side who found themselves in Ireland was to be taken prisoner and detained for the duration. The place of detention was known as the K-Lines Internment Camp, located in the Curragh.

It looked pretty much like you would expect any military prison to look like. Barbed wire fences, guard towers, and armed personnel guarding them. Cheap barracks buildings, raised up off the ground so as to make tunneling attempts impossible. It was located in the Kildare countryside, near a military base for reinforcements should the tenants become restless. With one minor detail of note in this particular instance. Allies and Axis were kept in the same camp. It didn’t seem efficient to build two camps, it wasn’t as if the Irish were expecting to take battalions of prisoners.

As you can imagine, however, having servicemen of both sides in close proximity was liable to result in some issues which needed to be resolved. The solution was to let the prisoners out on day passes. If the prisoners were out having fun and enjoying life, they’d feel less inclined to cause trouble, which might find them losing their privileges. So, they signed a promise to be back by a certain time, make no trouble, and out they went, to town to go to the cinema, the races, the pub, and what have you.

Now, one may ask, “what stops a prisoner from signing the form and just escaping to the embassy or North across the border”? After all, it’s every combatant prisoner’s duty to escape back to friendly forces. “The belligerent governments” is the answer. By stroke of geographic luck, Ireland was at the gateway to the Atlantic. Even if Eire was unwilling to allow a combatant the use of its ports for the Battle of the Atlantic, the belligerents were fairly desperate to not induce Eire to consider giving the –other- side the use of its ports. As a result, the interned prisoners on both sides were explicitly told “don’t break the parole rules, and don’t piss off the Irish.” Frankly, I think “don’t piss off an Irishman” is pretty good life advice anyway, but that’s beside the point.

Of course, a ‘legitimate’ escape was still fair play. If you managed to break out of the camp, through the wires, the guards etc and then made it to friendly grounds (not an easy task), then fair’s fair, it wouldn’t be held against the nation.

An enterprising barracks lawyer by the name of Bud Wolfe, an Nebraskan who joined the RAF to fight the Nazis, and not being particularly interested in spending a life of (paid) luxury in Ireland, thought he had found a way around this system. He signed out on parole, walked out the gate to a waiting taxi. Then said “Damnit, I forgot my gloves”, walked back in. Picked up his gloves, and walked back out the gate again. As far as he was concerned, he had signed out, returned by the deadline as promised, and then effected a legal, blatant escape out the gate. After he made it to Northern Ireland, he was arrested, the British decided that he had at least broken the spirit of the parole process, and sent him back to Ireland. His reception in the camp was not a happy one, the rest of the Allied prisoners were not best pleased at having lost their parole privileges for a week. A second escape attempt failed, he was recaptured shortly after breaking out.

We’re not in Kansas Nebraska any more

By a bit of a coincidence, Wolfe’s story actually ended in 2011: The wreckage of his aircraft was dug up from the peat bog in which it crashed, with various bits and pieces very well preserved. They even got a machinegun working again.

This somewhat unusual state of affairs could lead to some fairly abrupt introductions. One Canadian aircrew crashed near the Curragh, and, thinking they were in Scotland, decided to seek help at a pub that they found. Upon entering the saloon bar of the pub, they discovered it was full of Germans celebrating a birthday. This caused a little confusion. Their confusion was compounded a bit when the Germans forcefully instructed them that Allied party crashers were not welcome and that they were to go to their own bar (actually, at the public room in other side of the pub).

Wilkommen, have a beer, your colleagues are waiting. Oh, and you are now under arrest.

This story formed the basis of a rather execrable movie by the name of “The Bryllcreem Boys”, which you can watch for free on Hulu, at least if you’re in the US. Although the general plot is a terrible love triangle showing off Riverdance star Jean Butler (complete with dancing), it is partially redeemed by Gabriel Byrne as the camp commandant, and the depiction of the camp and its rules is reasonably close to the truth. For a more serious assessment, find a Canadian book (now out of print) named “Grounded in Eire.”

Going on another brief tangent, you may be aware of the fact that what we know as “World War II” (incidentally, there’s a Presidential Directive to the effect that that’s the conflict’s official name in the US) is not known by that name universally. Over on the former Soviet side of the house, it’s “The Great Patriotic War”. (Well, OK, they do distinguish between WWII and TGPW, but not in everyday conversation). The Soviet Union wasn’t the only country to give the conflict a less common name: In Eire, (Ireland), it was known as “The Emergency”

The background to this is that the Irish government wanted to enact emergency powers due to the unusual state of affairs which obtained in Europe in September 1939. The Irish Constitution granted the government such emergency powers in case of war, but it wasn’t entirely sure if the war in Europe counted. So the First Amendment to the Irish Constitution was approved, to add, in effect, that “state of war” could include “wars of which Ireland is not a part if the government thinks it’s important enough.” Once that little clarification was made, the Oireachtas (Parliament) passed its declaration of a state of emergency with the Emergency Powers Act. As a general rule, the Irish ruling bodies were not fans of the concept of acknowledging that there was a war going on which they had chosen not to be a part of. It went so far that when the son of a notable member of the Irish gentry in Malahide was killed when HMS Hood was sunk, his death was noted in the Irish Times as being due to a boating incident. As a result, the entire period 1939-1946 is known as “The Emergency.”

Leinster House, home of the Oireachtas

Now, this is all very interesting, but you’re probably wondering why I’m writing about Irish internment procedures on the Tanks portal. Bear with me.

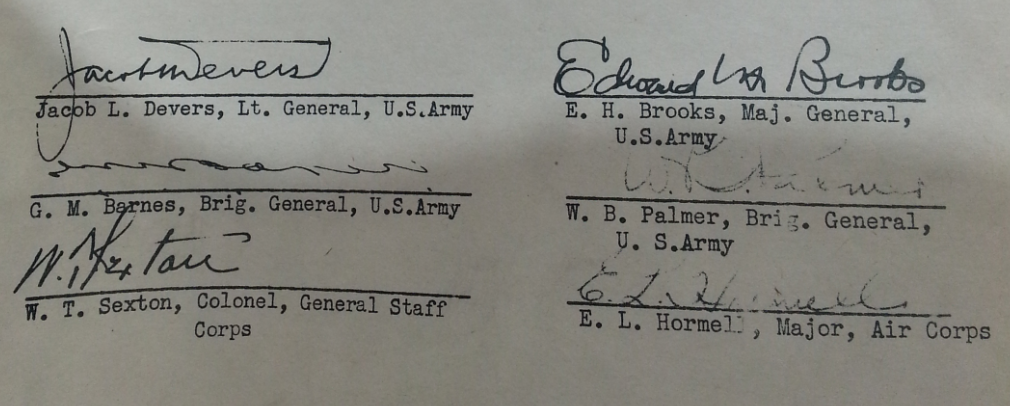

In December of 1942, Lieutenant General Jacob Devers, head of the Armored Force, decided to go on a fact-finding mission to the European Theatre of Operations to see how the tank units were holding up. Well, actually, it was mainly the North African Theatre of Operations, as European tank combat hadn’t really gotten off the ground. So he took with him a couple of colleagues, including one Major General Edward Brook, two Brigadier Generals named Gladeon Barnes and William Palmer, a Colonel William Thaddeus Sexton, and to carry the baggage, a Major Earl Hormell. They set off on December 14th, going south to Brazil, Ascension, The Gold Coast, Nigeria and Sudan, arriving Cairo five days later after a distance of 11,140 miles. After spending a little time with the British, they hopped over to Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. At the end of trip, they went to Gibraltar for a week to consolidate their findings 7-14 January. The result of all this flying around and taking people away from their jobs for a month was one page and a quarter of conclusions, and one half-page of recommendations (the other half is six signature blocks).

The conclusions of the fact finding mission were as follows:

- The M-4 Medium tank (General Sherman) is the best tank on the battlefield. [Chieftain’s note: Yes, they actually say “General Sherman” in the document. This is a nearly two years before Ordnance officially names the vehicle]

- The self-propelled 105mm howitzer is the best supporting light artillery weapon on the battlefield.

- The same tactical principles and doctrines taught by the Armored Force are today being successfully employed by the British Eighth Army. The British have evolved, independently in battle, methods of tank gunnery similar to latest Armored Force teachings.

- The present war is definitely one of guns. The attack is built around air, tanks, and artillery. Defense is built around air, concealed anti-tank guns, and artillery.

- In order for ground forces to advance, hostile aircraft must be rendered ineffective.

- To achieve success all combat units must be able to repel tanks and low flying aircraft with their own weapons. They must have 75mm antitank guns and .50 calibre anti-aircraft weapons organically assigned. Also 37mm antitank guns should be provided liberally to artillery trains and similar units.

- The separate tank destroyer arm is not a practical concept on the battlefield. Defensive anti-tank weapons are essentially artillery. Offensively, the weapon to beat a tank is a better tank. Sooner or later the issue between ground forces is settled in an armored battle – tank against tank. The concept of tank destroyer groups and brigades attempting to overcome equal numbers of hostile tanks is faulty unless the tank destroyers are actually better tanks than those of the enemy.

- A higher standard of discipline of American troops must be attained.

Five recommendations were put forward.

- That each infantry battalion include eight self-propelled 75mm anti-tank guns, that all battalions include four AA vehicles each mounting four .50 calibre machine guns.

- That 37mm anti-tank guns be provided liberally to artillery trains and similar troops.

- That the training facilities of Camp Hood, Texas, be used to produce and train anti-tank artillery personnel for all troops equipped with anti-tank guns of 75mm and larger caliber; surplus production, if any, to be sent to tank units.

- That “Tank Destroyer Battalions” be redesignated as “Anti-tank artillery battalions”, and their number limited to those sufficient for divisions and larger units.

- That better battle uniform including waterproof shoes be provided.

Their duty from their trip being completed, they took advantage of the fact that they were already on the other side of the Atlantic to go to the UK to check in with the goings-on there.

So they boarded their aircraft, a B-17 converted to a VIP transport role, departed Gibraltar, and set off North up the Atlantic’s Eastern edge, looping around to the West of France to avoid German interception. Their B-17 was named “Stinky”.

You can probably guess where this is going.

The daily diary of the Devers mission reads as follows:

“At 2:00pm, January 15th, departed from Gibraltar, weather splendid. At approximately 10:00am, just after daylight, sighted land which navigator described as Lundy Island. From the map, this island appeared to be 100 miles north of the point at which the plane should have turned east towards Port Reath. Retracing south, the contour of the coastline did not correspond to that on available maps. Searched for approximately two hours without finding a familiar landmark. The radio operator was unable to contact any stations. The navigator admitted that he was lost. The ground consisted of small grass fields traversed by stone walls. With the gasoline supply nearly exhausted, a crash landing was made near Athenry at 11:50am. The size of the field was such that after hitting the ground, the plane crashed through a stone wall at approximately 70 miles per hour. Although the plane was wrecked, the members of the party were uninjured. The plane was immediately surrounded by Irish civilians and members of the Home Guard. The local inhabitants were very friendly, offered food and any medical assistance necessary. Shortly thereafter, representatives of the Eire Army arrived and took charge of the situation”

So, we now have the interesting situation that on 15th January 1943, the General in charge of all US tank doctrine and training, the General in charge of developing all the equipment used by the US Army, the General in charge of evaluating the merit of future armored vehicles (The head of the Special Armored Vehicles Board), the Commanding General 11th Armored Division (tapped to command 2nd Armored in Normandy), and their advisors, are detained and facing internment for the duration of the war with a bunch of Germans. One can only speculate what would happen to the future of the US military’s armored vehicle development.

The end is, as you can imagine, a little anticlimactic. After all, most of you will have never heard of this incident, so obviously not much came of it.

In reality, though Ireland was officially neutral, it was ‘neutral in favour of the allies’, most famously allowing the Donegal Corridor which cut a lot of flight time off RAF Coastal Command aircraft transiting to partake in the Battle of the Atlantic. A quirk in the policy was that though Ireland in early 1943 was still interning combatants, it had by 1942 decided to define the term a little loosely. If the belligerent personnel had ended up in Ireland as the result of a combat operation, they were interned. If, however, it was decided that they were not undertaking a combat mission at the time, they were sent North. And thus, after determining (over lunch in an Athenry hotel), that Stinky was just doing a ferry flight and not a bombing raid her passengers and crew set off by car at about 20:30, crossing the border into the UK from Sligo at about 2am.

Pilot Officer Wolfe and his colleagues, however, had to remain in the K-Lines until they were released in October 1943. By that point, the Irish had decided that it was a bit of a bad lot, there were more Allies crashing in Ireland than Axis (understandably, given the geography), so the K-Lines were closed. About half of the 260 or so Germans declined repatriation, probably not least because some of them had found girlfriends during their evenings out. There were still some internments later in the war, but they were brief, small in number, and in a different camp under different rules.