The first group of assassins to be found in the historical record is that of the Hashshashin who operated in Persia, Syria, and Turkey, eventually spreading throughout the Middle East. They assassinated their political and financial foes until the organization met its own demise in the middle of the 13th century.

When we think of an assassin we see a figure lurking and waiting in the shadows, killing for dark political reasons, with little thought for passions of the heart or interest in money. And that isn’t far off from how the actual assassins operated in the 11th through 13th centuries.

The origins of the name “Hashshashin” or “assassin” are shrouded in mystery. The common belief is that the name comes from the Arabic word “hashishi” which means “hashish users.” People writing about the group reported that they committed their deeds under the influence of hashish and the name naturally flowed from that.

It is possible that this explanation developed after the fact as a convenient way to lend credence to an original story but we have no way of reliably verifying this. In truth, the group strictly adhered to the Koran when it forbade the use of intoxicants. There is another, perhaps more compelling explanation in the Egyptian word “hashasheen” which translates to “noisy people” or “troublemakers.”

When the fortress of the Assassins was conquered in 1256, their library was destroyed so there are no written historical accounts from the sect itself available to us. Accounts of their existence that have survived into our times come in the form of the recollections of their enemies or European accounts, which were surely embellished as they were passed along.

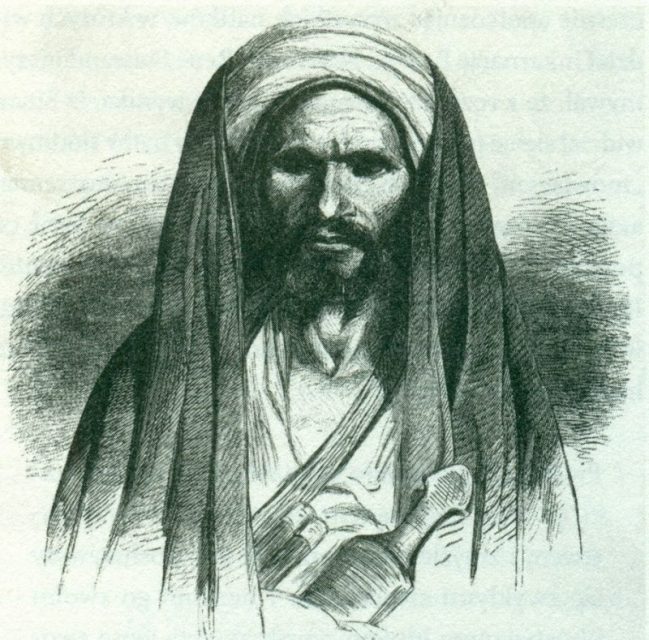

We do know that the Assassins were an offshoot of the Ismaili sect of Shia Islam. The founder of the group was a Nizari Ismaili missionary named Hassan-i Sabbah. He led his followers into the castle of the king of Dayam and successfully pulled off a bloodless coup in 1090.

Based out of a fortress on a mountaintop, Sabbah and those who followed him developed a network of strongholds and challenged the Seljuk Turks, who were Sunni Muslims in control of Persia at the time. This is when the group first becomes known as the “Hashshashin” – Assassins in English.

The Assassins carefully studied their targets, learning their language and culture. They would then plant a spy in the inner circle of the intended victim. The spy sometimes spent years gaining the trust of the victim and their advisers. When the opportunity arose, the assassin would stab the unsuspecting sultan, vizier or mullah.

An assassin martyred for the cause (which typically happened shortly after the attack) was assured a place in Paradise. Assassins were typically merciless in carrying out their missions. This caused panic among the leaders of Middle Eastern countries, and many of them began wearing chain mail or armor under their clothes for protection.

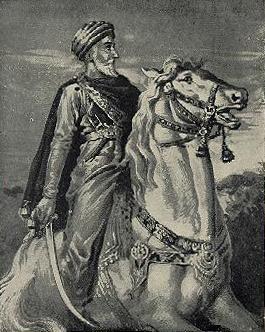

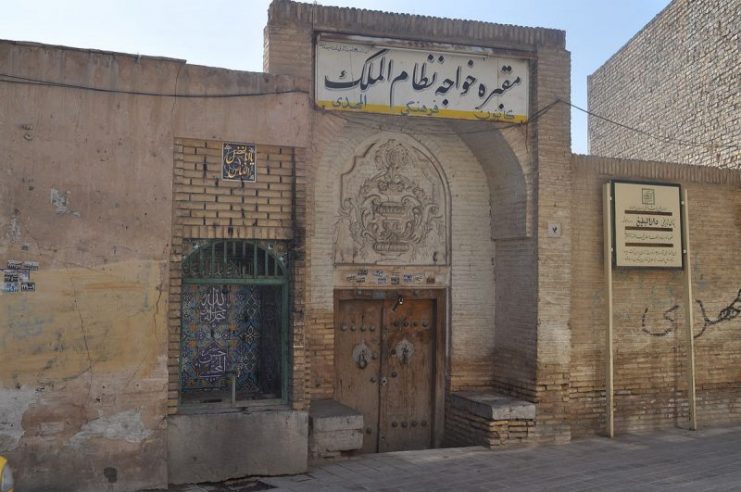

Typically, the Assassins focused their attacks on Seljuk Turks or their allies. The first known victim was Nizam al-Mulk, a Persian who served as a vizier in the Seljuk court. An Assassin disguised as a Sufi mystic killed him in 1092. In 1131, a Sunni caliph by the name of Mustarshid was killed during a dispute over succession rights.

The Sharif of the holy city of Mecca had his cousin killed by the Assassins in 1213. He was convinced that he was the actual intended victim due to his close resemblance to his cousin. He reacted by taking all Persian and Syrian pilgrims as hostages until a rich woman from Alamut paid the ransom.

Shi’ites in Persia had a long history of being mistreated by the ruling Sunni Muslims that ran the Caliphate for centuries. As the Sunni’s power waned in the 10th and 11th centuries and as Christian crusaders attacked in the eastern Mediterranean, the Shi’a were empowered to seize the moment. The Assassins were no match in a direct confrontation with the Sunni Seljuks. Instead, they chose to carry out their terror missions from their mountaintop strongholds throughout Persia and Syria.

The ruler of Khwarezm (part of present-day Uzbekistan) made a major tactical error in 1219. He murdered a group of Mongol traders in his city. This infuriated Genghis Khan who led his army into Central Asia to get his revenge against Khwarezm.

The Assassins aligned with the Mongols, which left the strongholds of the Assassins as the only areas in Persia that were not under the control of the Mongols. It is estimated that the group controlled as many as 100 fortresses at the time.

The Mongols were occupied with battles in other areas and for the most part, left the Assassins alone. The grandson of Genghis Khan, Mongke Khan, however, was determined to rule over all of the Middle East and attacked the seat of the Caliphate, the city of Baghdad. This enraged the Assassins and they formulated a plan to kill Khan.

Their plan failed and Khan now distrusted the Assassins and decided to destroy them and end their threat to his reign. The Mongols attacked the Assassins with everything they had. The leader of the Assassins at the time surrendered and was paraded before all of the Assassin strongholds and, one by one, they surrendered as well.

The Mongols razed all of the fortresses so that the Assassins had nowhere to regroup. Eventually, the Mongols executed the leader of the Assassins and his retinue, bringing an end to Assassins once and for all.