By 1200 Christianity was the dominant religious force throughout almost all of Europe; however, one group of pagans, in the last stronghold of their beliefs, was preparing to make a stand. These were the Samogitians of Lithuania. Today Samogitians are a subgroup of Lithuanians, and some consider themselves to be a unique ethnic group.

In 1236, they primarily lived in what is today Northern Lithuania. In the 1200s they generally did not have any written language, and those who did write were almost universally Christian converts, so there are few reliable sources regarding their culture.

It is known that they were pagan, loosely organized (sometimes labeled “tribal,” although their leadership structure adopted some feudal elements), and remarkably devoted to their religion to the point of being fiercely resistant to conversion and Christian military occupation.

On the other side stood the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. Also known as Sword Brethren, the Livonian Brothers were a Catholic military and crusading order in what is now modern-day Latvia and Lithuania.

Although technically vassals of the Bishop of Livonia, in practice they were essentially independent, to the point where they defied the Bishop and conquered lands in the name of other kings, and lived in their own strongholds.

They had been founded as a part of the Livonian Crusades (also known as the Northern Crusades), first by the Bishop of Riga in 1202; two years later they were recognized by Pope Innocent III.

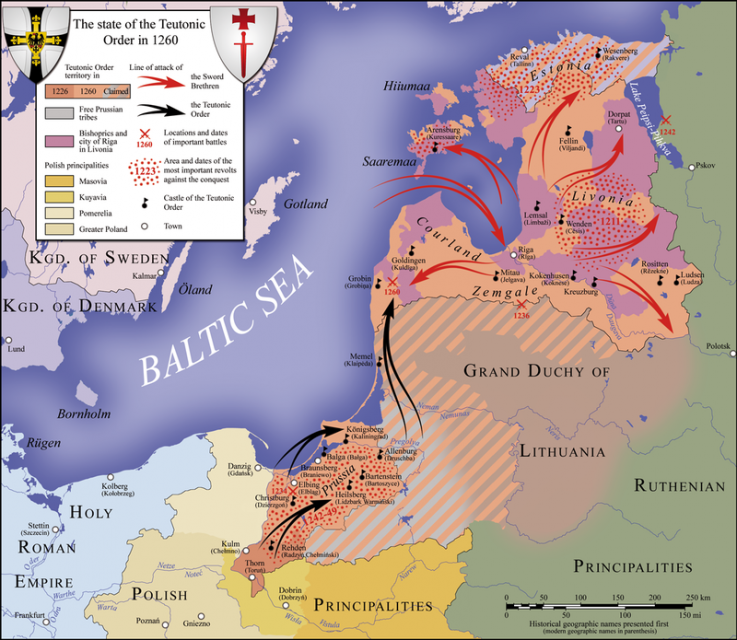

Although perhaps less well known than the Middle Eastern Crusades, the Northern Crusades took place throughout the Baltics between 1193, when Pope Celestine III called for a Northern European Crusade, and 1290 when the last battle was fought. By 1236 the Crusaders had turned their eyes towards the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the last pagan polity in Europe.

When Pope Gregory IX declared a Crusade against Lithuania in early 1236, it did not take long for German knights to arrive and join up with the Sword Brothers. They did not take long to demand action.

The Sword Brothers seemed to have little to fear from the loosely organized pagans in Lithuania. After all, the Sword Brethren had, in only a few decades of existence, managed to conqueror many similar pagan peoples, including the Semigallians, Selonians, Oeselians, and Curonians.

The Sword Brethren gathered a significant force to invade Samogitian land, including at least 50 knights and a large number of locals as foot soldiers. They were under the leadership of their Master, Volkwin von Naumburg zu Winterstätten, who had been elected from their own ranks. All-in-all their force totaled around 3,000.

However, the Samogitians were not going to back down so easily, and raised over 4,000 troops themselves, including light cavalry. Although it is not definitively known who their leader was on this occasion, it was most likely Vykintas, the Duke of Samogitia and a staunch pagan. On September 22nd of 1236, these forces would clash in the battle of Saule.

Crusader forces had encountered essentially no resistance up to that point, and had been raiding and looting settlements for several days before the pagans could muster a force. The knights, temporarily satisfied, began to return north but found part of the Samogitian forces at a river crossing in a swampland.

Rather than attempt to force their way through the Samogitians, they decided to make camp for the night. When the sun rose, the Crusaders found a much larger Samogitian force had arrived. The Samogitians soon attacked the Crusader camp, and the battle quickly turned in the pagans’ favor.

The heavily armored and mounted knights were ill-equipped for fighting in a swampland and were soon bogged down. In contrast, the Lithuanians were lightly armed and could maneuver much more easily.

The Lithuanian light cavalry found significant success in the battle, especially in the use of light javelins that could pierce armor at short range. Soon many of the Crusaders had fallen, including Master Volkwin, and their native allies began to flee. Ultimately, as many as 60 knights, all noble born, were slaughtered in the battle, along with the vast majority of the Livonian Sword Brothers’ native allies.

During their broken retreat, some sources report that even more of the Crusading forces were killed by other pagans before they could reach Christian lands. Samogitian causalities are known to have been significantly lower than the Crusaders’ losses.

The result of the battle was devastating to the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. Master Volkwin would turn out to be the last Master the Brothers would have as an independent order, as the Order was so decimated by this loss that they were forced to fold into the Teutonic Order, although they were allowed to exist as an autonomous sub-order.

Renamed the Livonian Order, they would never again approach the power they had in the early 1200s, although they would continue to play an active role in spreading Christianity at the end of a sword throughout the Baltics.

This loss not only devastated the Livonians but also inspired massive uprisings by pagans they had previously subjugated. It would take until 1290 for Christianity to regain control over the last of these tribes.

Although the Battle of Saule perhaps only delayed the inevitable Christian conquest and conversion of the Baltic, reverberations of the battle can be felt even to this day. There is still a Samogitian dialect, and to some degree an ethnic identity, in Lithuania.

Additionally, the battle plays a significant enough role in the cultural consciousness that multiple towns compete to claim to be the site of the battle – Šiauliai in Lithuania and Bauska in Latvia are the most commonly cited locations, although others also claim to be the battle site.

Read more stories like this – Knights Hospitaller: The Great Siege of Malta

The anniversary of the battle is recognized as “Baltic Unity Day” in both Lithuania and Latvia. Although the majority of Samogitians have been Catholic since the end of the Livonian Crusade, a small number of Lithuanians identify their religion as Romuva, a modern re-creation of ancient Baltic paganism, to this day.