In May 1940, and over a year before the US entered World War II, a group of Pittsburgh citizens offered a reward of $1 million to anyone who captured Adolf Hitler.

Samuel Harden Church, at the time the president of the Carnegie Institute, led a group of 50 men and women who pledged to provide the money to anyone who delivered Hitler “alive, unwounded and unhurt” to the League of Nations to be tried for his “crimes against the peace and dignity of the world.”

The reward was only available for one month. No one claimed the money, worth almost $18 million today. It did, however, generate international attention.

The idea came from discussions that had taken place over a two to three month period at Downtown’s Duquesne Club.

In an article published in the New York Times on May 1, 1940, Church said that he thought that there was power in the idea, especially because it did not reward assassination.

He said that he had received word that Hitler intended to launch an attack on the Western front, even if it were to cost 500,000 lives. Church and the other Pittsburgh citizens that were willing to fund the plan were hoping to save a lot of lives by arranging to have Hitler removed from the picture before the bloodshed began in earnest.

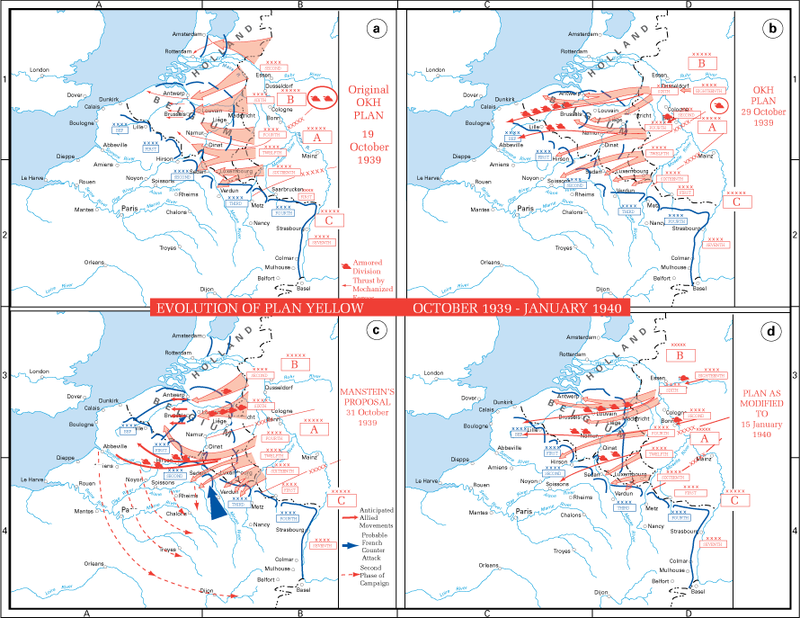

When the Pittsburgh plan was announced, Hitler was chancellor of Germany and the leader of the Nazi party. Eight months earlier, the Germans had invaded Poland, thus beginning World War II. On May 10, 1940, just as Church’s group feared, Hitler attacked France, thus opening the Western Front. 150,000 Germans and 360,000 French died or were wounded before France surrendered to Germany.

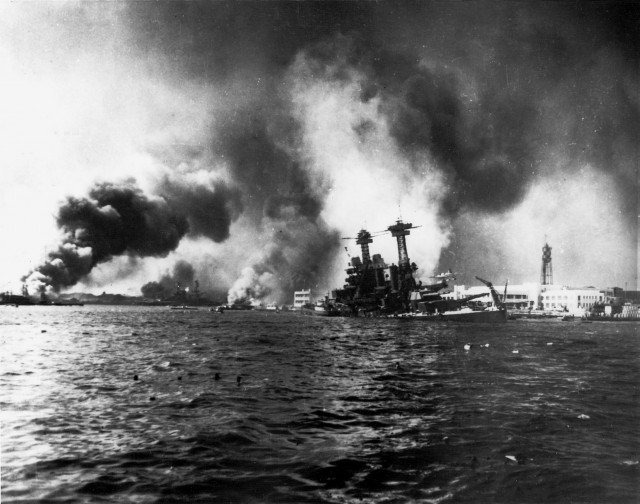

The United States would not join the war until after being attacked by Japan at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

On May 2, 1940, a follow-up article in the Times stated that the reactions to the Pittsburgh plan ranged from anger to ridicule and seriousness.

A group in Blowing Rock, North Carolina, wrote to the Times to call the idea ridiculous. “We hung the Kaiser in 1917. Now they propose to hang Hitler on the same trumped-up charges,” the group wrote.

In the years leading up to America’s involvement in World War II, US citizens were very divided about whether the country should enter the war. Charles Lindbergh, the famous aviator, became the de facto “leader” of the isolationist movement. Many politicians were also against American involvement in what they saw as a European problem.

The isolationists saw the oceans as impenetrable barriers preventing any European or Asian nation from attacking US shores. Lack of technology prevented news from those continents from reaching the US, and a lack of transportation options prevented most US citizens from traveling to Europe or Asia. They were seen as exotic, far-off locations that could not directly affect the US.

Furthermore, Lindbergh and others agreed with the Nazis that some races were superior to others. While acts like Kristallnacht unnerved Lindbergh, he publicly blamed minority groups, such as the Jews, for trying to drag the US into a war he felt was none of America’s business.

It was against this backdrop that the Pittsburgh group offered their bounty. In equal parts an attempt to prevent the US from needing to enter the war by eliminating the main cause of the conflict and an attempt to show the isolationists the moral degradation of the Nazi leadership, the bounty was above all an attempt to get people talking about the problem rather than just taking sides.

However, Hitler remained the leader of the German forces until they surrendered to the Allies following his death by suicide in his bunker on April 30, 1945.