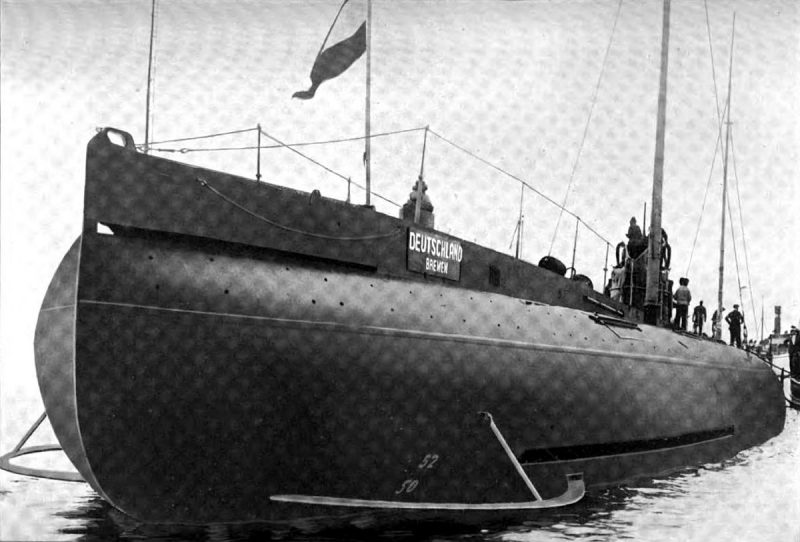

100 years ago this month, the U-Boat Deutschland, a German submarine, visited Baltimore on an alleged business venture. It spent a couple of weeks in South Baltimore’s Locust Point during the peak of World War I.

The country was watching when the German Unterseeboot arrived while Germany was at war with England and France. “The U-Deutschland was something of a celebrity during World War I. To German citizens, she was Germany twisting the [British] lion’s tail and making a mockery of the [the British naval] blockade,” wrote historian Dwight R. Messimer in his 2015 book The Baltimore Sabotage Cell.

Baltimore in 1916 had a large German-speaking population that cheered the ship when it arrived and prayed for its safe arrival home when it left. At the time, the U.S. was neutral. It didn’t declare war on Germany until April 1917.

The captain of the U-Boat, Paul Koenig, became a celebrity in Baltimore. When he entered the lobby of the Hotel Belvedere, the house band played The Watch on the Rhein. While dining at a Baltimore Country Club banquet, Koenig was approached by Lois Marshall, the wife of U.S. Vice President Thomas R. Marshall. She demanded a tour of the Deutschland and received it.

Hundreds of miles away a New York harbor with a munitions depot, known as Black Tom Island, exploded. Tons of gunpowder, shells, and bullets intended to be delivered to Britain and France blew up. Later, it was found that there was a connection between the explosion, the Deutschland, and a Baltimore resident.

While Koenig was the public face of the Deutschland’s visit, Paul Hilken, a businessman in Baltimore with German heritage, was the person behind the scenes. Hilken was the chief of the Baltimore division of the North German Lloyd steamship company with an office building downtown. He graduated from City College and lived in Roland Park. He was a pillar of Zion Lutheran church.

After the war, a post-war reparations commission found that Hilken was acting under orders of the German government when he set up the shipping firm to receive the Deutschland and its cargo, which was supposed to be dyes used for fabrics.

Messimer writes in his book that Hilken had been on an earlier trip to Germany when he was recruited by the German secret service, Sektion Politik, to sabotage munitions bound for England, France, and Russia – enemies of Germany. Hilken’s office downtown was the headquarters for the secret operations.

Hilken paid thousands of dollars to operatives from the Deutschland to take care of Black Tom Island. It worked – the explosions killed at least five people and shattered windows in Manhattan across the Hudson. After the explosion, the FBI traced his involvement in the operation, so Hilken left Baltimore. He was called to testify before the reparations committee but faced no legal action. He died in New London, Conn, in 1959.