As Remembrance Sunday neared, poppies, the flowers that came to symbolize the fallen of the Great War, once again doted the lapels of many in Britain, Canada, Australia, US and other countries. But how did these flowers came into that status?

The Beginning

Poppies grew abundantly in the fields of France and Belgium, the same lands where the front lines of the Great War were located. This may be the reason why Canadian poet John McCrae used poppy imagery in his short but famous poem about the futility of war, In Flanders Field.

However, the wearing of poppy pins as a symbol of remembering the fallen started in the US. American professor Moina Michael was so inspired by McCrae’s short verse that she penned a piece of her own in response to it in 1918. It was entitled We Shall Keep the Faith. She, then, arrived with the idea of wearing poppy flower pins as a way of remembering the soldiers of WWI as she taught disabled servicemen.

She brought her idea with her in a conference in Paris, France in 1920 even going as far as distributing some poppy pins to other delegates. Anna Guérin, a Frenchwoman and one of the delegates, copied her idea and made poppy pins of her own which she sold in London in 1921. That same year, the Royal British Legion founder and British Expeditionary Force commander in the First World War, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, adopted the symbol.

Canada, New Zealand, Australia and even the US followed Haig’s adoption of the flower and so, the lowly poppy became the official symbol of those who feel in the Great War.

The poppy pins produced then on were used to raise monetary funds for soldiers and their families.

The ‘Red Sea’ in the Tower of London’s Moat

This year, in commemoration of the centenary of the outbreak of the Great War, artist Paul Cummins along with his team has filled the moat surrounding the Tower of London with ceramic poppies. In all, he and his team made 888,246 ceramic versions of the flower, one for each British serviceman who died during the Great War. The installation, officially named Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red, has attracted a large crowd ever since it was started.

Nevertheless, it isn’t without criticisms.

Just this month, the Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones censured the project as something ‘inward looking’ — overseeing and remembering only the dead within the British country while ignoring those who fell from the other nations involved in the Great War. Jones even posed a question of why not also commemorating the dead of Germany.

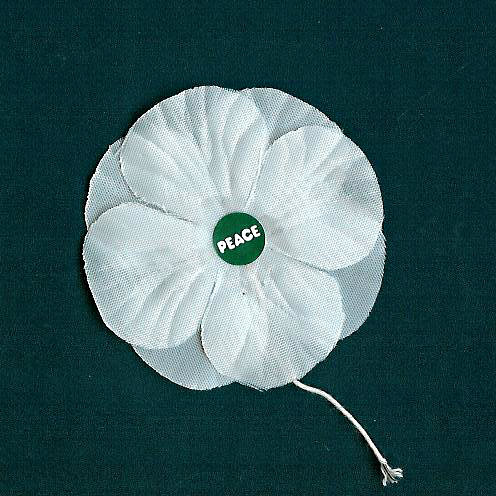

White Poppies and the Great War

Red poppies aren’t the only ones used during Remembrance Day. Some lapels bear white poppies as well. The latter is worn in favor of a pacifist view about wars — it commemorates the dead but objects battling in general. But their use oftentimes spark anger. Some people, including Margaret Thatcher, see hem as a disrespect to those who fell during the war.

The Women’s Guild, a cooperative in Britain, was the one to invent the white poppies way back in 1933. They are currently sold by the Peace Pledge Union.