Every year, thousands of re-enactors from all over the world descend on Normandy for the first week of June. They fill up campsites and town squares, and they are seen at nearly all of the events and commemorations. Re-enactors are now firmly part of the anniversary landscape along with the Veterans’ Associations, the tour groups, the parades, and the pageantry.

In 1989, 1994, and 1999, I was in Normandy as a re-enactor myself, wearing the scratchy wool of the British soldier of D-Day. Then, a few years later, I gave up the hobby when my age and waistline started making me feel uncomfortable.

Since then I have been at the anniversaries in different capacities. I have been a tour guide in Normandy since 2002 and have organized commemorative events both large and small. I have witnessed the number of re-enactors increase each year.

How are they perceived, these re-enactors, from outside of their hobby? This is a question I think I may be qualified to answer because of my background. It may be hurtful to say but, from outside of the hobby, re-enactment is often viewed with bewilderment and confusion. In some cases, people are actually offended by what they see as “dressing up.”

What can be done to change this perception? That is quite simple: talk about and improve the standards of re-enactors at events. Because I am regularly embarrassed, shocked, and even offended by the behavior and appearance of some of the re-enactors who attend these ceremonies.

As such, I want to begin a dialogue within the re-enactment hobby about accountability, how standards matter, and, more generally, about what a re-enactor’s role is as a participant at these events, both now and in the future.

The WW2 veterans will not be coming forever, and the re-enactors with their jeeps and tanks will draw more and more attention. So it is important that re-enactors attempt to address how they are viewed by the general public.

Here’s the bottom-line: the minute you put on a WW2 uniform in Normandy (or at any of the other battlefields) you are essentially assuming the role of a young person who actually fought and may have died there 75 years ago. This is a very different scenario to, for example, a works party in England where people dress up in Dads Army costumes for fun.

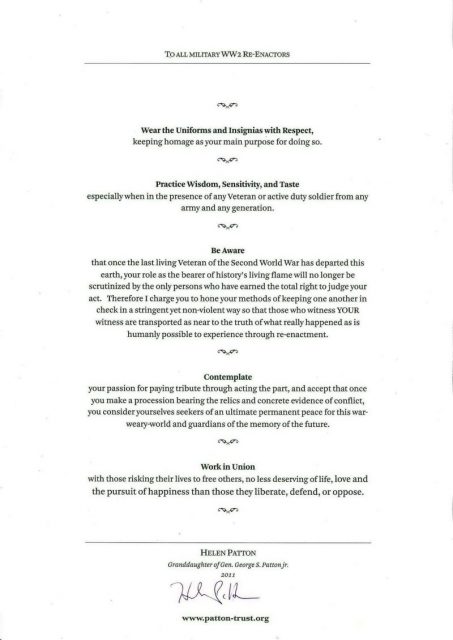

Recently, I have been discussing with my friend Helen Patton (the General’s granddaughter) the Re-enactor Charter she wrote a few years. It looks at the role of re-enactors and how they become a “bearer of history’s living flame.”

I am currently trying to organize a public event in Normandy next month. With Helen Patton’s participation as well as that of re-enactors, tour guides, museum owners, and others, I want to start a discussion about what can be done to improve standards. It may not be much but it’s a start, and I believe it’s important to start somewhere.

There will be some things that are difficult to tackle. The average age of re-enactors will, of course, be older than that of the actual participants. So, try and choose a role befitting your age – there is nothing wrong with portraying airfield mechanics, drivers, cooks, and rear-line troops. Not everyone can be an “Easy Company” Paratrooper.

Try a more obscure but important unit. Waistlines expand, hair goes grey, and we are generally taller and wider than our wartime predecessors. But, some things are easy to achieve – hair length and style, for example. Cut your hair to a wartime length and shave your beard. Press your uniform, remove modern jewelry, and cover modern tattoos.

Then, there are things you can improve with regards to your demeanor and behavior.

Keep your hands out of your pockets, and don’t stand around drinking. Be respectful at monuments and memorials, and generally comport yourselves in a military manner.

What annoys me the most is when I see the “half and half” uniforms. By which I mean (for example) the wearing of jump boots and pants, but combined with a modern t-shirt and baseball cap. Either wear a uniform or don’t. “Do or not do, there is no try” to quote a small green alien!

Beyond the 300lb, 60-year-old and above American paratroopers, the worst examples I have seen include a man sporting dreadlocks, British battledress, and a beret pulled down to the wrong side together with US jump pants.

I’ve seen someone dressed as Field-Marshal Rommel complete with modern motorcycle goggles and a desert uniform converted from a white dinner jacket.

I’ve seen hipster beards on Grenadier Guards, face-tattoos of English football teams on German WW2 soldiers, and home-made uniforms with insignia drawn on with a Sharpie. But it is the behavior that is the most upsetting.

I saw a Jeep owner trying to take the chains down at the entrance to a CWGC cemetery so that he could get a photo of his pride and joy in front of the graves.

I’ve seen people drinking from beer cans during National Anthems, urinating in the streets, and re-enactors walk around supermarkets with sub-machine guns.

This needs to stop.

I urge re-enactors to read Helen’s charter below and consider what you can do to improve. Not only will you improve your own look and feel great satisfaction about that, but you’ll be adding to the atmosphere and authenticity of such events, and that’s going to result in more fun for everyone — you included.

Above all, let’s start talking. You can find me on Twitter, and I can be reached by e-mail.

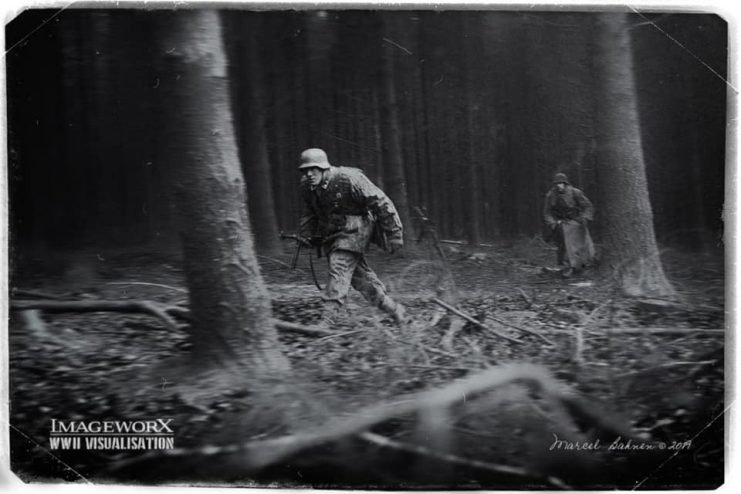

I will end by saying: I still love living history re-enactment and the amazing photos I was sent by friends while writing this article (some of which are displayed here) are proof that there are many great people out there honoring the WW2 generation.