Despite the deaths of thousands in the First World War, and the disappearance of centuries’ old empires, the “war to end all wars’ was transformative. U.S. civil liberties, the appearance of wristwatches and global politics, were all a result of that war.

As the centennial of American’s entry into the war is this month, Ernie Freeberg and Vejas Liulevicius, two experts from the University of Tennessee (UT), look back on how the conflict continues to exert influence today.

Many of the current events today, such as strife in the Middle East, is owed to decisions made after the war, said Liulevicius, the Lindsay Young Professor of History and director of the UT Center for the Study of War and Society.

The borders determined at the time are the ones causing strife today, he said.

The assassination in June 1914 of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, successor to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, started the war, which would drag on for four years. His death triggered the Ottoman Empire and Germany, Ferdinand’s allies, to enter the fray and make war against Great Britain, Russia, and Austria.

The war caused the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Russia, Germany, and Austria.

The regions they had controlled earlier came under French and British control with political borders redrawn.

New countries such as Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Yugoslavia appeared on maps.

France and Britain divvied up the Middle East along random lines and created borders for today’s Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and Kuwait. Tribes were divided, or ethnic groups were squeezed together that for centuries had engaged in feuds.

American president Woodrow Wilson had hoped to have the United States remain a neutral arbiter of the war, but over time America entered the conflict on April 6, 1917, to lend some support to allies.

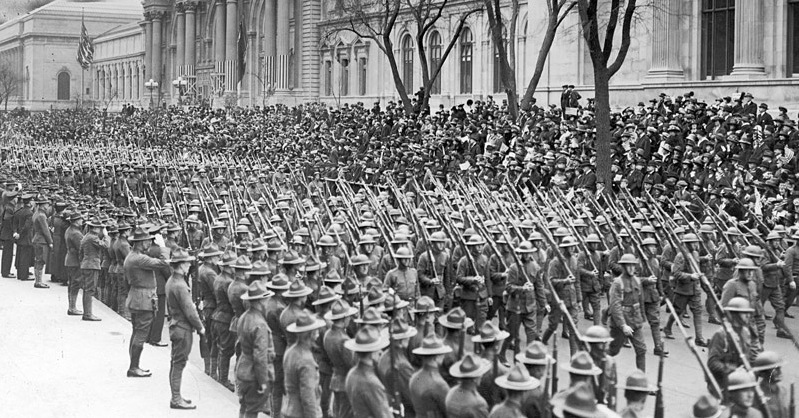

People have strong recollections of victory parades and patriotism concerning World War I, but what is forgotten is how strongly the disagreements were, said Freeberg, head of the Department of History. Many felt the war in Europe was not an American problem to remedy, and the sympathies of American immigrants such as Jewish, Irish, and Germans were divided. They were disinclined to support the Allied Powers.

Wilson’s plan to generate support for the war by encouraging public opinion prompted the rise of propaganda.

Out of this emerged stylized ‘I Want You for U.S. Army’ Uncle Sam promotional posters, Liberty Bonds, and films starring actors such as Charlie Chaplain. Wilson also started the draft, which conscripted almost three million men for the army.

But Wilson’s efforts had a negative side, Freeberg explained. There was a pronounced move to stifle dissent, which spawned the Sedition Act. Over 2,000 dissenters were charged.

The American Civil Liberties Union came out of this to try to maintain the rights of conscientious objectors and then attempted to free them from jail, Freeberg said, adding citizens have more freedom now compared to then. The organized defence of free speech continues today.

Wristwatches taken for granted today had their genesis in World War I, invented to replace weighty pocket watches men wore on chains, which were too awkward to synchronize attacks on the enemy’s front lines.

When the war started, many in European cities embraced the conflict, eagerly signed up for a fast and wonderful adventure, but became disillusioned as it dragged on, Freeberg said. They worried it had been about nothing; this lead to an ‘America First’ desire and isolationism, which prevented Franklin Roosevelt from reacting to fascism’s rise.

It also influenced America’s tardy and muted response to the Second World War as news of atrocities and the Holocaust were publicized.

By the end of the conflict, 10 million people lost their lives; the stage had been set for the rise of communism in Russia, fascism in Italy, and World War II, started by Germany.

Some positives did emerge, such as the ideas of self-determination and diplomacy. The League of Nations, forerunner of the United Nations, was created to encourage the concept of collective security for countries and open diplomacy instead of understandings made behind closed doors, Freeberg said.

To ensure that people do not forget the lessons of World War I, the UT Centre for the Study of War and Society has arranged a number of events this spring. The centre recently was given a $1,200 grant from the Library of America to assist the effort, Tennessee Today reported.

The programming started in February with a lecture concerning the role of 380,000 black soldiers who labored and fought in the US Army during the war. It drew attention to the legacy and struggles of the servicemen off and on the battleground, abroad and at home.