When we think of war, many of us envision images of their fellow citizens suffering. We think of soldiers who are hurt or killed overseas. We think of veterans who come home with life-changing injuries trying to recover. We think of the families of the young men and women lost at war.

However, it was not always like this. Prior to the Vietnam War, most Americans didn’t get to see these images. American journalists, the government, and the military didn’t want Americans to think of the war in this way. It was not until the 1960s and 1970s, during and after the Vietnam War, that things started to move in a different direction.

Today, with war in the Middle-East at times dominating the news, Americans are flooded with information and images depicting U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan and Iran. We are exposed at least weekly to the major news networks’ stories highlighting American military war heroes.

We see hour-long documentaries covering the perspective of families of the troops, both stationed overseas and killed in action. During Vietnam, rarely did journalists broadcast these intimate stories. Nor did they personalize the stories of our troops who were killed or injured while stationed abroad.

To put this into perspective, during the Vietnam War, the New York Times published the names of only 726 out of the 58,220 American soldiers killed in Vietnam. Only 16 biographical references were made, and only 14 photos of military servicemen found their way onto the pages of the Times.

After searching all of the newspaper’s articles from that period, only five articles expressed the reaction of family members who had lost sons, fathers, and brothers in the Vietnam War. And only two articles talked about the suffering of soldiers posted in Vietnam.

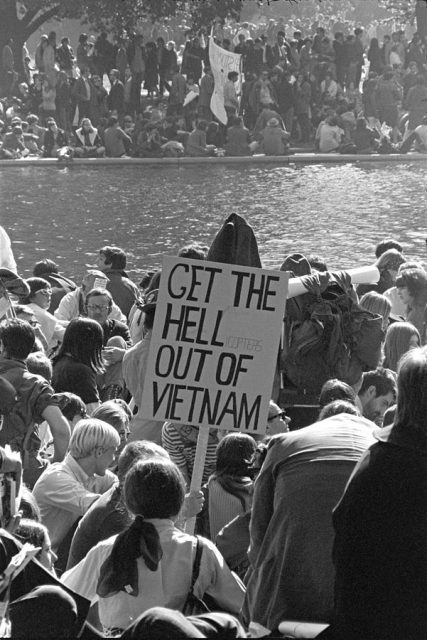

The United States suffered major casualties throughout the Vietnam War. Americans were reacting to the news of these devastating casualties in ways previously unseen by the government.

In order to avoid a long-term lack of domestic support for the war effort, the US needed to find a new way to honor the troops. The chances of victory in Vietnam were quickly dwindling, and it was important to find a way to honor those fighting for our country.

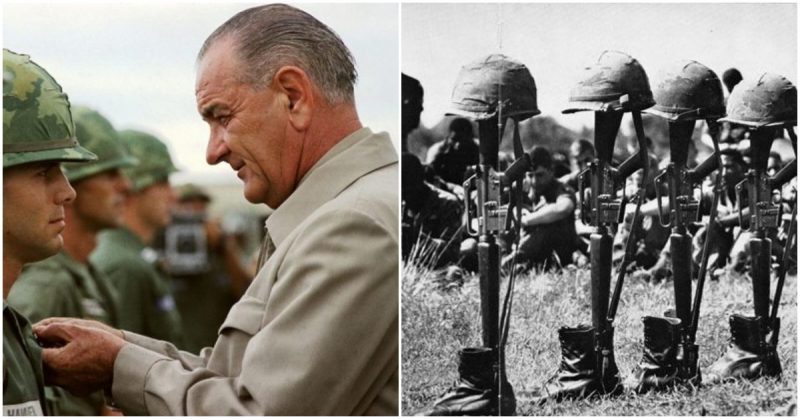

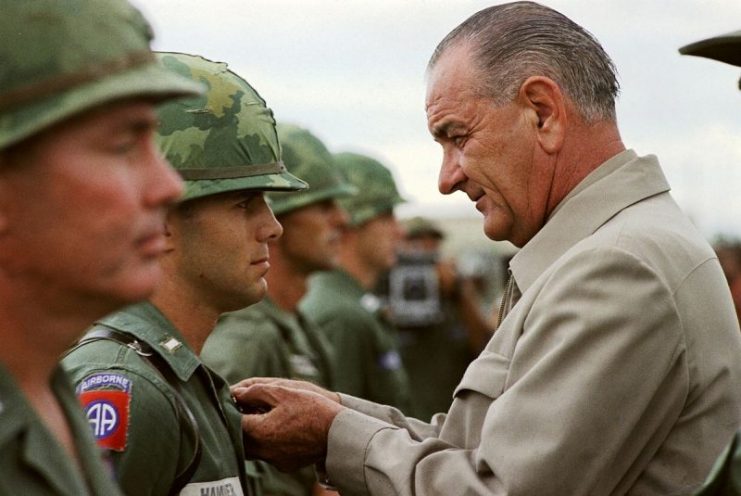

The US changed the way they approached honoring their military service members in a few major ways. First, they changed the basis on which they awarded the Medal of Honor. Prior to Vietnam, the Medal of Honor was typically awarded to soldiers who had excelled offensively in war.

In other words, if a certain soldier killed a large number of enemy troops, and thereby contributed to victory, he may be awarded the Medal of Honor. During and following Vietnam, the criteria for awarding the Medal of Honor changed. The medal was now being awarded to men who performed acts of heroism in defending or saving his fellow soldiers.

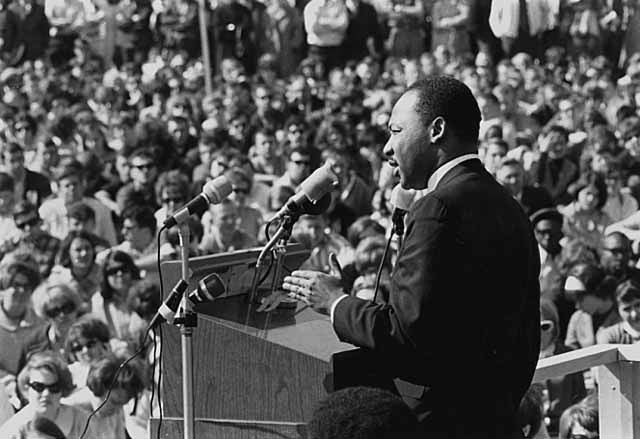

Another way in which the US changed its honoring of US troops was in how the military handed down discipline. Prior to the Vietnam War, military leaders were renowned for their harsh discipline of new recruits and enlisted men. The 1960s and 70s, however, were a time of individual autonomy and self-expression.

The military had no choice but to embrace these values by allowing their own men to enjoy the same expressive freedoms US civilians did. Journalists began publishing photographs of soldiers wearing buttons proclaiming “Love” and “Ambushed at Credibility Gap.” Never before had soldiers had this sort of expressive freedom.

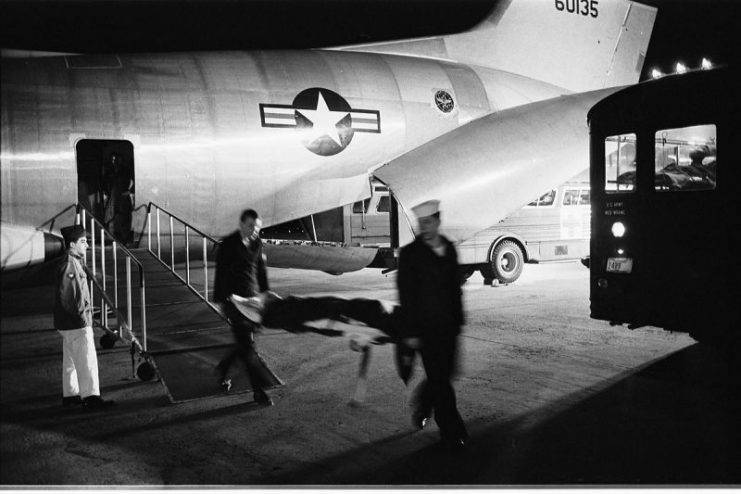

Finally, the government and military changed the way in which the families of fallen soldiers were treated. Prior to Vietnam, when a soldier died in combat, an impersonal telegram was sent to the family’s home.

As a response to America’s reaction to the high number of casualties in the Vietnam War, the US Military changed this policy and started sending a representative of the military to the home of the family instead. Families were notified, in person, of the death of a loved one rather than by a telegram.

It was not only the families of the fallen who were honored. The US changed the way in which they treated and handled prisoners of war. Families of POWs started to band together and demand respect and honor for their loved ones.

For the first time, military personnel and journalists began to meet with the families and loved ones of soldiers who became prisoners of war. They wanted to show America the emotions felt by the families of these heroes.

The cultural changes in how we view war and honor our troops have persisted up to today. The ways in which the US fights wars has changed. Casualties are much lower today than they were in Vietnam. One of the reasons for this is that the US military has changed its approach to war in foreign lands.

Instead of the ground troops we saw in Vietnam, the military now uses high altitude bombing, drones, and heavily armed vehicles. Although this does lead to much fewer US casualties, it does typically increase the number of civilian casualties abroad. It also reduces the amount of interaction the US troops have with the locals which, inevitably, can reduce local support for the US cause.

Vietnam did not make Americans pacifists. It did, however, make us more concerned with the well-being and safety of our troops. The end of the draft following the Vietnam War led to an all-volunteer military force.

Because of this, new recruits have to be treated with much more respect today than they did decades ago. As a result, America will continue to honor their military troops for protecting each other even during coflicts in which American does not fare so well.

While Americans have most always respected those who serve, following the Vietnam War the ways in which we do so have changed significantly and in many different areas including the press and the military itself.