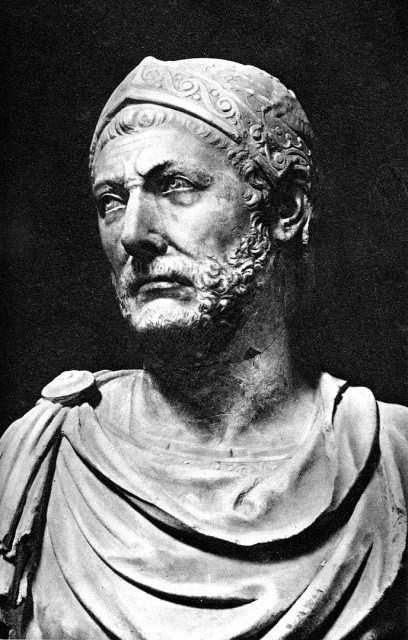

It is dawn, August 2, 216 BC and lightning is about to strike the Roman Republic. On a ridge overlooking the expansive plain, Hannibal Barca watches as a massive Roman force.

Eight enormous legions consisting of 87,000 infantry and cavalry – marches directly, irresistibly toward his troops arranged on the ground below.

Two years before he had led his army over the Alps and descended into Northern Italy to harass and defeat the Romans time-and-again.

Now, led by the Consul Varro, the Romans have assembled a massive force for one purpose only – to destroy Hannibal and his army.

He watches as dust swirls around the approaching Romans, their breastplates glinting in the rays of the rising the sun. He’s been expecting them.

Feigning retreat, Hannibal has drawn the Romans for days across miles of dry, barren land to the small village of Cannae in southeastern Italy, where he now intends to fight.

He has at his disposal at best 50,000 infantry and cavalry, but the dismal odds do not bother him. Near Cannae, he has placed his forward line in a crescent at the mouth of a small valley that rises like the letter V from the plain.

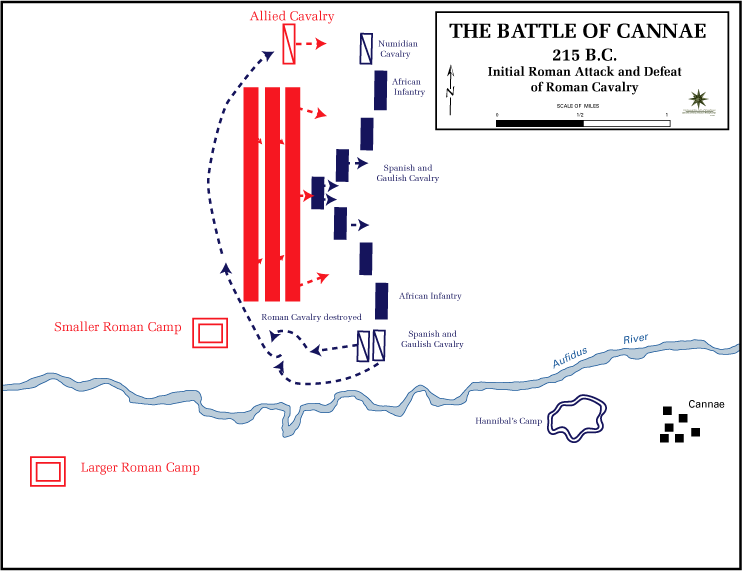

Upon each flank Hannibal has positioned his finest Carthaginian infantry, somewhat detached on small knolls. His heavy cavalry – a substantial force – also waits in hiding on the sloping ground behind Cannae.

The Romans are the greatest military power of the day, their legions well-trained, armed, and led. But Hannibal has studied their methods carefully, and because he knows precisely how they fight, he knows precisely how to defeat them.

Through the swirling dust the Romans march on, a formation stretching over a mile from flank-to-flank, a massive, seemingly unstoppable force.

Finally spotting the Carthaginians arrayed for battle ahead, the Romans press hurriedly forward. At the mouth of the valley, both sides meet in a terrifying collision of flashing swords, flying spears, screams, and horrific bloodletting.

Slowly the Carthaginians give ground, backing into the valley – just as Hannibal has ordered.

The Romans, sensing victory – expecting to overwhelm the center of the Carthaginian line – press ever forward, unaware they are being lured into a trap.

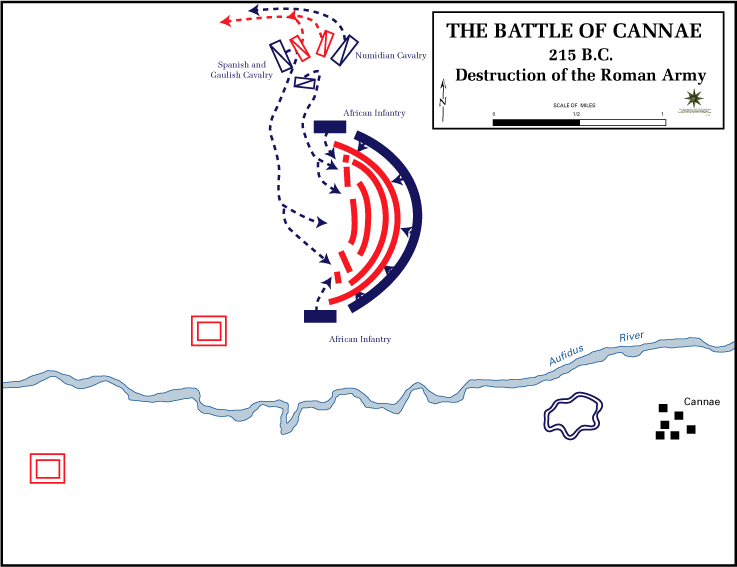

From above the Carthaginian leader watches as the massive Roman formations crush into the ever-narrowing terrain below.

Satisfied, he turns and nods. A smoke signal goes up, and the detached Carthaginian infantry sweep down upon both exposed flanks of the unsuspecting Romans. Hannibal’s cavalry thunders out from hiding, driving off the Roman cavalry then returning to attack the Romans from behind.

Just like that, the legions have been surrounded. Moreover, because of the narrowing constraints of the landscape the Roman units cannot maneuver, change fronts, or even bring their vast numerical superiority to bear.

They have been trapped virtually shoulder-to-shoulder, like cattle in an enormous pen.

All day the Carthaginians hack away at the edges of the Roman formation, reducing it by the hour, until late in the afternoon the Romans are no more.

The historian Polybius writes that on the Valley floor some 76,000 Romans and allies lay dead. Another 10,000 have been captured. The Carthaginians suffer a mere 5,700 casualties. Their victory is unparalleled.

Hannibal’s astonishing victory over a substantially superior foe will go down as perhaps the greatest military victory of all time.

According to military historian Robert L. O’Connell, Rome’s losses that day totaled “more dead soldiers than any other army on any single day of combat in the entire course of Western military history.”

As such, Cannae has cast a very long shadow over Western military thought and traditions, virtually sanctified over time as the “holy grail” of martial brilliance.

Many commanders have tried unsuccessfully to replicate Hannibal’s stunning double-envelopment: Frederick the Great, von Molke, and von Schlieffen, among others.

It is said Napoleon marched his army through numerous Alpine passes just to walk in the great Carthaginian’s footprints, while Dwight Eisenhower wrote that every military leader “tries to duplicate in modern war the classic example of Cannae.”

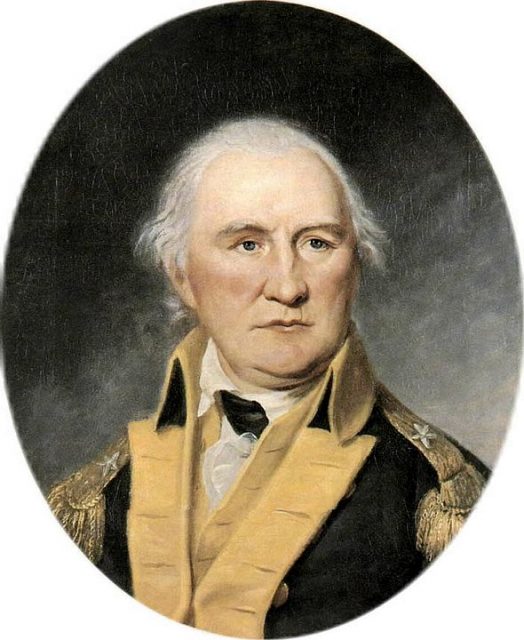

We now fast-forward to January 1781, for lightning is about to strike again. Pursued by a strong British force under command of Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton, American general Daniel Morgan feigns retreat, drawing the weary British ever deeper into the cold, wintery backwoods of South Carolina.

Tarleton has risen to become General Charles Cornwallis’s handyman of choice. Cornwallis, a crafty and hard-driving general, has used Tarleton to impose his will across the rebellious countryside, and in this the young cavalryman has not disappointed.

But Tarleton has made his reputation generally running roughshod over small bodies of American cavalry or backwoods militia; Morgan, a proven battlefield commander, may prove a tougher test.

Moving sluggishly across the wet, freezing landscape, Morgan finally locates ground he likes at the Cowpens, a crossroads where local farmers bring their herds for branding.

The American and British forces are roughly equal in numbers, but the British are pursuing with an elite force, while two thirds of Morgan’s men are rural militia, untrained in the basics of battlefield warfare.

Morgan understands that if he is defeated the American Revolution in the South will collapse, but he realizes his militia will never stand-up to British bayonets.

He also knows that Tarleton is a young, extremely aggressive officer, with a penchant for immediate attack against all odds. What will he do?

Like Hannibal, Morgan devises a plan to turn his command’s deficiencies into pluses, while simultaneously using Tarleton’s over aggressiveness to lure him into a trap.

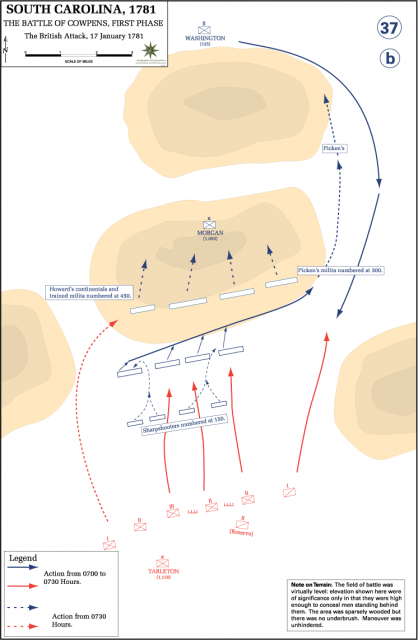

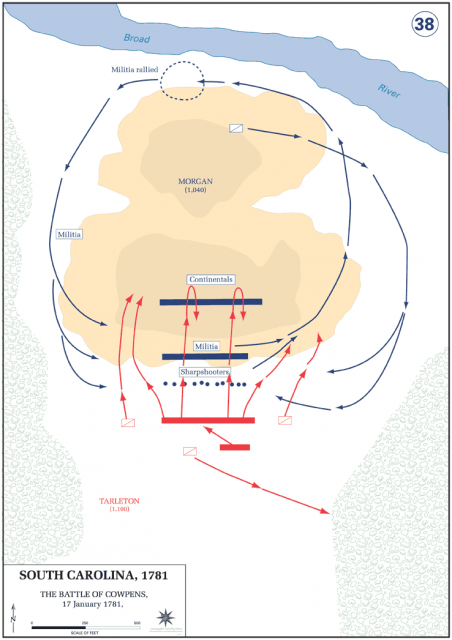

Cowpens is a wooded area of small hills and swales that Morgan believes can be used to advantage. Rather than forming one battle line, he decides upon three, the first a small group of crack rifleman, the last two hidden by the terrain.

The first and second lines will be militia, asked only to fire twice before falling back to the final line of veteran Continentals.

This will spare them from British bayonets, while giving Tarleton the appearance of retreat, thus luring the Redcoats into Morgan’s trap. At the final line both the militia and Continentals will make a stand.

At daybreak, January 17, Tarleton’s detachment marches into Cowpens, 1,100 strong. Initially facing only a small contingent of riflemen, they immediately deploy for combat, as Morgan’s crack shots blast away, felling many Redcoats before falling back, as planned.

Tarleton, noticing the Americans in apparent retreat, leads the British forward even before they are properly formed, only then to stumble headfirst into the second American line, precisely as Morgan had anticipated.

The militia stand and unleash a furious blast of musketry at virtually pointblank range, savaging the Redcoat infantry, before falling back themselves to the waiting line of Continentals.

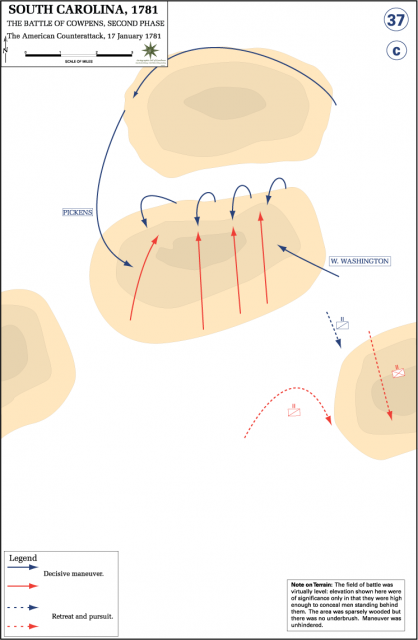

There both sides slug it out before an error on the American side sends the British rushing forward in hopes of victory. But the Continentals recover and fire a volley into the faces of the charging Redcoats, then lower the bayonet themselves.

Stunned, the British turn and run for their lives, Continentals on their heels. American militia and cavalry spontaneously join the pursuit, the militia closing on both flanks of the fleeing British as the cavalry sweeps around, surrounding the Redcoats in a scene eerily reminiscent of Cannae.

Fortunately for American posterity, the British throw down their weapons, and slaughter is avoided. The British have fought with great spirit and bravery, but they have been undone by their commander’s rash decisions. Tarleton, along with a few dragoons, escapes, but his entire detachment has been annihilated. American casualties are trivial.

Morgan’s well executed plan saved the Revolution in the South for the American cause. Moreover, he is one of the few battlefield commanders who has ever come close to duplicating Hannibal’s masterpiece, this in a tactical scheme entirely of his own creation.

While Cowpens was hardly of the magnitude or sophistication of Cannae, I suspect it was a victory that even the great Carthaginian would have admired.

The United States rejoiced wildly upon receiving word of Morgan’s success, but today his dramatic victory seems all but forgotten.

For a full list of his books simply click on: amazon.com/author/jimstempel

Jim Stempel is a speaker and author of numerous articles and eight books on American history, spirituality, and warfare. These include The Nature of War: Origins and Evolution of Violent Conflict, and his most recent, American Hannibal: The Extraordinary Account of Revolutionary War Hero Daniel Morgan at the Battle of Cowpens.