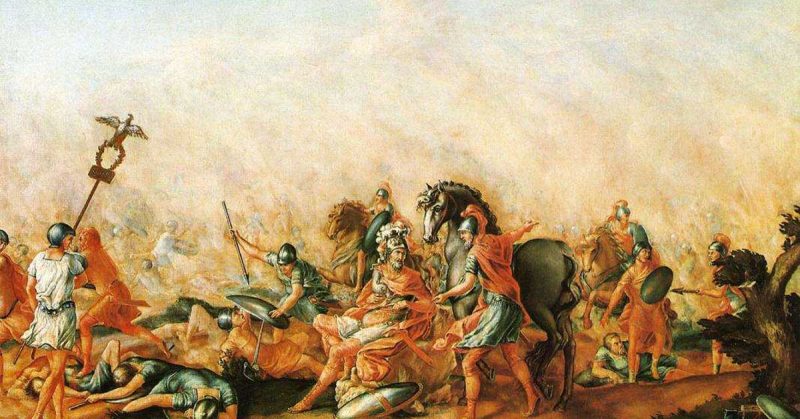

The battle of Cannae was an almost perfect tactical victory for Hannibal Barca. Facing a Roman army almost twice the size on a level field, Hannibal was able to efficiently command a force that stretched well over a mile and secure a dominating victory.

For some background, the second Punic War started in 219-218 BCE as both Rome and Carthage were growing in power and Hannibal decided to get the ball rolling by sacking a Roman-allied city in Iberia (Spain) known as Saguntum. Once war was declared Hannibal made a surprising journey over the Alps and into Italy.

Once in Italy, Hannibal won a victory at the Trebia River by concealing some elite units in the brush near the river crossing and having them ambush the Romans once the main lines met. At Lake Trasimene Hannibal successfully hid well over half of his force and ambushed a Roman force in marching order, pinning them up against the lake and decimating their force. Hannibal followed up that victory by ambushing the 4,000 cavalry on their way to reinforce the Romans near Trasimene.

Following the Trasimene ambush the Romans elected Fabius Maximus as dictator for a year. Using delaying tactics, Fabius kept Rome safe while Hannibal travelled throughout Italy seeking to turn Rome’s Italian allies to his side. After a year, Hannibal was still in Italy and the Romans were getting restless. As soon as Fabius’ dictatorship expired two new Consuls were elected, Aemilius Paullus, and Terentius Varro.

In an effort to defeat Hannibal with brute force the Consuls joined up to create an army of eight legions, usually Consuls went separate ways with a four legion army. In addition these legions, normally around 4,000 infantry and 200 cavalry, were increased to 5,000 infantry and 300 cavalry. These numbers were approximately matched by the Roman allies making up a total Roman force of over about 80,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry.

Hannibal’s force was a multicultural mix of specialist units from all over the Western Mediterranean. At Cannae a core of fierce Gallic warriors made up the center. These Gauls were largely recruited from areas of Northern Italy that the Romans had not yet conquered. Generations of warring had bred into the Gauls a burning hatred of Rome and they would be counted on to hold the center if only through sheer refusal to run from the Romans.

On either side of the Gauls were Iberian (Spanish) light infantry. These tribal warriors fought with light armor and small shields but were armed with a lethal falcata sword. Built with a slight bend inwards and a sharp point, this short sword could stab as easily as it could slash or bludgeon. Iberian infantry were renowned for their athleticism in combat.

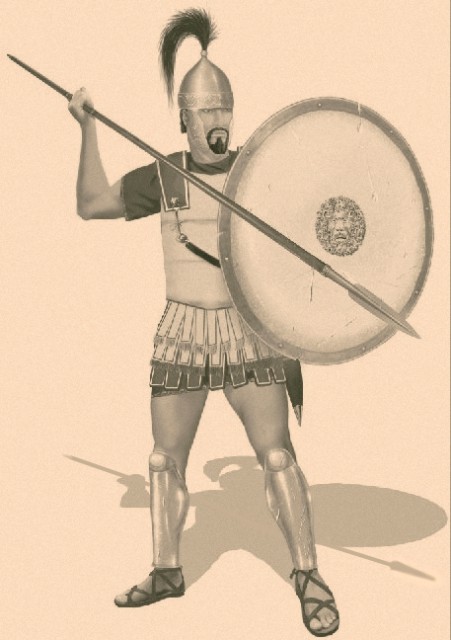

Holding the flanks of the infantry were the elite African infantry from Carthage. These infantry fought in a phalanx style, utilizing long spears in a packed formation, though it is debated if these troops adopted Roman arms and armor from past Italian victories, it seems most likely that they still fought in a style close to a Greek or even a Macedonian phalanx.

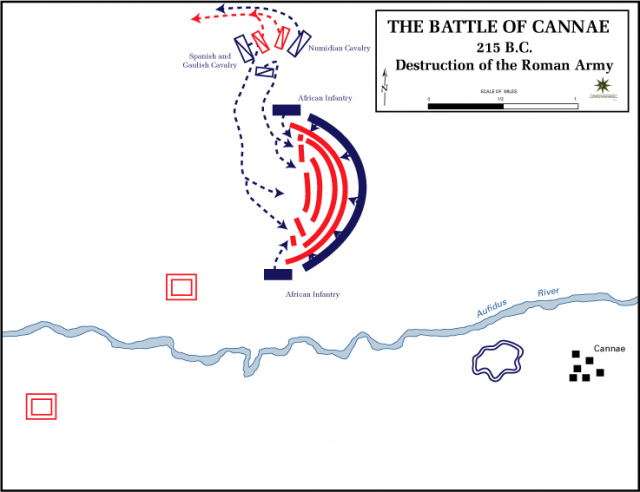

Hannibal brought out his army in a most unusual fashion, by placing his Gauls forward in the center having each unit align farther back as they reached the wings, Hannibal created a crescent shaped formation with his Gauls exposed to the full brunt of the Romans. Hannibal did have an advantage in cavalry, but spread it unevenly, placing 6,500 heavier cavalry on the left side of the formation under Hasdrubal while Hanno commanded the 3,500 light Numidian cavalry. The Numidian cavalry was extremely light, but expert cavalry; they rode bareback and controlled their mounts with a simple loop of rope rather than reins. They fought with a cluster of javelins to throw or fight melee with. Most other cavalry during this time fought in the old Greek manner with varying levels of armor, spears and swords.

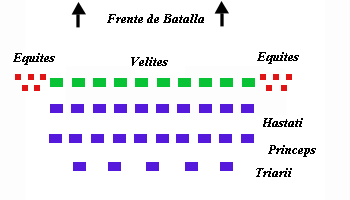

Facing the much smaller Carthaginian force, The 80,000 Roman infantry was arranged in four main lines. The front lines were the youngest and poorest Velites, skirmishers who exchanged missiles before the main lines engaged. The front line of heavy infantry was the Hastati. These were young and unproven men, put in the front because they had the youthful strength to make an early impact while guaranteeing firsthand fighting experience. The middle line of Principes was comprised of fighting men in the prime, with a blend of experience and youth being around 30-40 years old. The last line was the Triarii, the most battle-hardened men tasked with holding the flanks and providing a final forward push if needed. Though composed of hardened fighters, the Triarii were the smallest of the infantry groups.

The Romans often fought in their trademark checkerboard formation with each maniple of men leaving a maniple-sized gap between other maniples. That was not the case at Cannae; the infantry were instead arranged in a wide block of infantry with little to no gaps between the maniples. The cavalry were evenly divided with about 3,200 cavalry on either flank.

Though the Roman commander for that day, Varro, has been vilified for his defeat, his plan was actually quite sound in theory and there is every indication it was planned in conjunction with Aemilius Paullus. Based on past battles it was clear that the Roman infantry was effective when it was allowed to do what it did best and churn through enemy infantry, at the battle of the Trebia River, several thousand infantry ploughed right though the enemy center despite the rest of the battle crumbling around them. With 80,000 men the hope was that they would overpower the Carthaginians doing what Romans did best.

As the Romans marched to engage the young Hastati were eager to fight and gravitated toward the Gauls in the center. As more Hastati on the wings heard and saw the fighting in the middle, more and more men inched inwards creating a funnel shape directed on the exposed Gauls. The Gauls absolutely refused to break, aided all the more by Hannibal who had taken position directly behind them. Though they didn’t run the sheer pressure of the focused Roman attack pushed the Gauls back until they moved past the Iberians allowing them to engage.

While the Roman infantry were turning the Carthaginian convex formation into a concave one, Hannibal sent his unbalanced cavalry to attack the Roman’s cavalry. On the Carthaginian right the fighting was more or less even, with the agile Numidians simply holding the Romans as long as they could. On the Carthaginian left the 6,500 cavalry quickly overwhelmed the smaller Roman force and sent them from the battlefield. In a move much easier ordered than followed in the ancient world, the Carthaginian cavalry were able to efficiently break away from the chase, swing around to the right flank and combine with the Numidians to break the rest of the Roman cavalry.

While the cavalry fled behind them, the Roman infantry focused their efforts on breaking through the center causing a compact ball of Romans with more Carthaginian units engaging. Finally the African infantry utilized their phalanx formation and spears by swinging like a gate on either side of the Romans and pinning the sides. At this point the Romans were surrounded on three sides, but still had vastly greater numbers. In no time, however, the 8-10,000 Carthaginian cavalry slammed into the rear of the Roman formation, completing the encirclement.

Once encircled the forward momentum of the Romans faltered and they became so tightly packed that they could hardly swing their swords. A group of around 10,000 Romans were able to push through and escape, likely by exploiting a gap between the different Carthaginian units. The rest of the Romans were completely trapped and the battle turned into a slaughter. As many as 70,000 Romans were killed including Aemilius Paullus, over 80 men of senatorial rank or higher and a previous Consul. Varro returned to Rome in shame but was actually applauded on his return for not fleeing from Rome.

The aftermath of Cannae was almost as impactful as the actual battle. Countless southern Italian cities defected to Hannibal and the Romans were in such a panic that they reverted to human sacrifice to appease the gods. The immediate survivors gathered in small villages and debated leaving to sell their services overseas. At this point the young Scipio, later known as Scipio Africanus, reaffirmed his and everyone else’s commitment to Rome.

Hannibal seems to have had a clear path to march on Rome, but his victorious army was not without damage. A battle that large took a huge toll, with about 8,000 casualties but even the psychological wounds would play a factor here. Livy describes a scene while Carthaginians were looking for survivors. A living Numidian soldier was found pinned down by a dead Roman. The Numidian had severe lacerations on his face and nose. As the Roman was dying he lashed out with his hands and teeth to do as much damage as he could.

The Battle of Cannae was a brutal struggle and one of the largest melee focused battles in history with no archers and few skirmishers most of the fighting was decided on a hand to hand basis. Though there were other disastrous defeats for Rome; they lost Germany after the Battle of Teutoburg forest, Adrianople saw an emperor fall for the first time but when looking at the battle itself, none was a worse defeat than that suffered at Cannae. The second Punic War was a monumental conflict for Rome and the way they refused to quit and bounced back after suffering a string of horrendous losses to eventually win the war was a testament to their strong character. This fight to the death personality combined with the experience gained through the war allowed the Republic to go on to become a Mediterranean superpower.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online