Historically there are very few military forces that can feasibly live up to the standards set by the cliche of ‘live fast, die young and leave a good looking corpse,’ but the Russian Hussars are one of them. Their bravery was without bounds, often launching into the thick of the fighting to ignite the battle. They were the first to involve themselves in counterattacks, first into quick onslaughts.

They were human and despite their fearlessness and ferocity, they rode into battle with few protections and suffered heavy casualties. That’s why their reputation for playing hard during peacetime is well warranted. They defended their honor and were always ready to fight to their dying breaths. These were truly the variety of men who required the high adventure life to uphold their spirit.

The first Russian Hussar regiments did not last long. The eighteenth century brought significant developments for the Hussars in the Russian army. Catherine, the Great’s Ukrainian Cossack army was reformed into five hussar regiments, including one regiment of royal guard hussars. Entry was simple – a young man could go to the cities of Minsk or Mogilev (now Belarus) where the drafts took place.

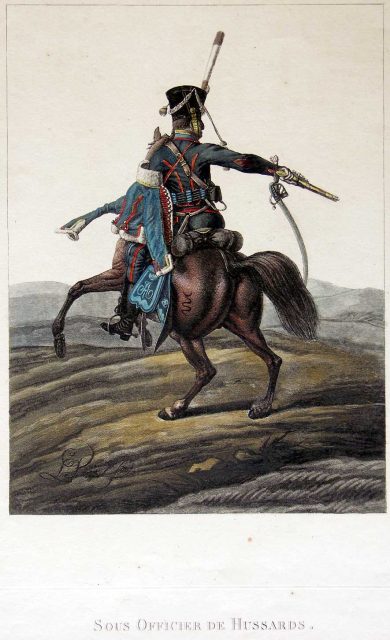

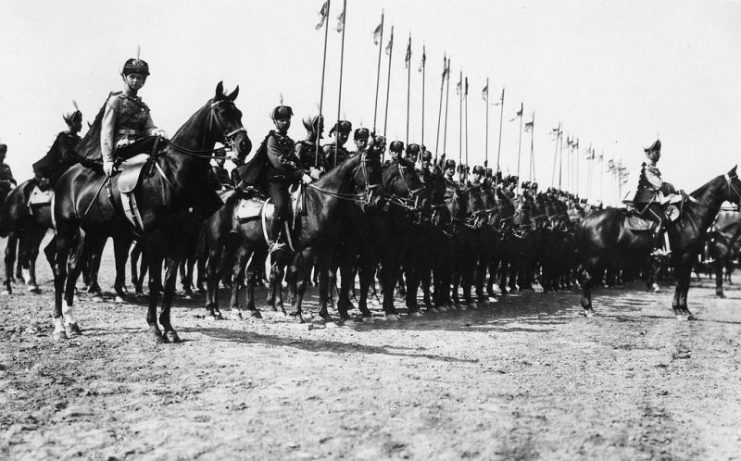

Armed with sabers, carbines, and pistols, the Hussars were light cavalry. Their uniforms were bright, with a different set for each regiment, and were initially inspired by the uniforms worn by the early Hungarian hussars. Requiring a surfeit of bravery and recklessness, the distinctive feature of the hussars was the speed and abruptness of their attacks. A hussar required elite physical fitness, attained and maintained through relentless drilling.

The point of endless drilling was to build the muscle memory required to be able to perform the task at hand without failure, and without the requirement of conscious thought, under any circumstance.

Hence, the Hussars were trained to load the hand pistol, for example, so they could do it at dusk, during pouring rain, and while mounted on a moving horse. If they failed in their drilling or were slow in loading, they faced severe punishments such as two hundred hits on the back with an iron rod.

The rest of their lives of service were similarly demanding, including a 5 a.m wake-up to feed their horses and then themselves, before the endless drilling and horsemanship training, which ended at 6 p.m.

Everything from time to signals to change formations, directions to attack or retreat, were handled by trumpeters, who were thought to be the aristocracy of the Hussars. All together, they had over fifty trumpet signals, each of which would be difficult to perform mid-gallop, but Hussar trumpeters would still manage to play.

But the peculiar rituals didn’t stop there. The Hussars had an unusual internal culture, including the consumption of alcohol.

“It looked very soldierly: the floor is covered with carpets, in the center is a pot, sugar is burning soaked in rum; around, in rows, the feasters are seated, holding pistols in their hands… When the sugar has melted, the champagne is added, and the ready zzhenka (a drink made of rum, champagne, and melted sugar) is poured into the pistols – that’s how the bender starts,” Count Osten-Sacken wrote.

Drinking alone was considered lewd, and among their beverages of choice were champagne, rum, punch, and mint vodka. It was proper comportment to drink a choice beverage for a month or two, and then swap it out for something else.

Read another story from us: Key Developments in the History of Cavalry

Naturally, the drinking culture of the Hussars celebrated their own escapades. These were the drunken escapades of elite soldiers seeking moments of raucous fun with the full philosophical fatalism of the career soldier who knows that there is a distinct probability that the next deployment may be his last.