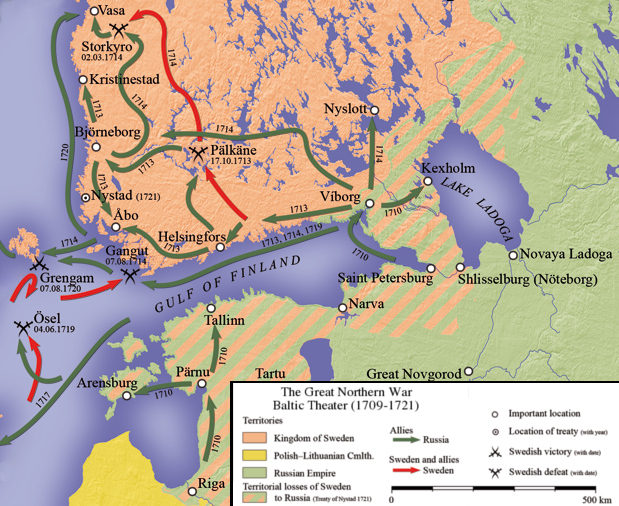

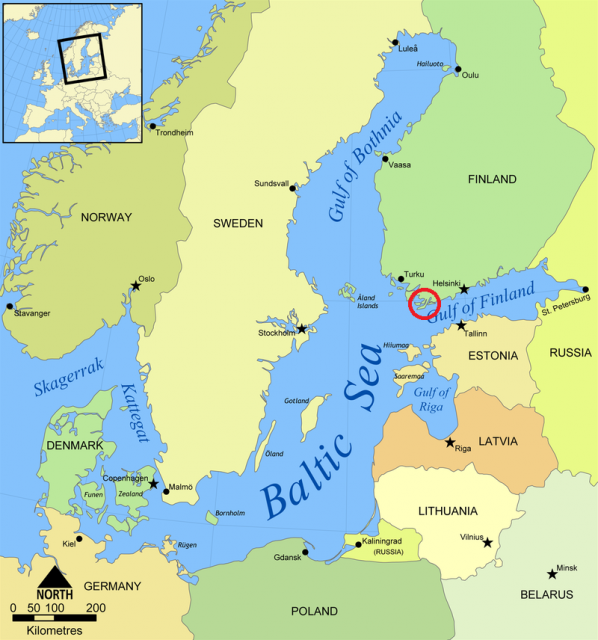

The Great Northern War (1700 – 1721) pitted two great warrior leaders against one another for over 20 years – Peter I of Russia and Charles XII of Sweden. The results of the war vastly increased the size of European Russia and allowed Peter the Great’s ambition for a modern navy in the Baltic Sea to come to fruition. The first significant step in that process was Russia’s defeat of the Swedish Navy in the Battle of Gangut off the Southern tip of Finland near Hanko.

Background

Following the victories by his army in the region now known as St. Petersburg and the area of Lake Ladoga, the Russians had established a port that provided them access to the Baltic Sea. Just as important, it allowed the flow of trade and goods from the very north of Russia to the very south of the country, located on the coasts of the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea, through a system of rivers.

Peter I immediately began fortifying the mouth of the Neva River by creating the Peter and Paul Fortress and the Kronstadt Island fortress. Additionally, he began the construction of a modern navy. Within a few years and following a decisive land victory against Charles XII at Poltava, the Russian naval strength had increased significantly. Furthermore, victories in the Baltic countries of what are now Finland, Estonia, and Latvia, gave Peter increased access to the Baltic.

His most troubling problem was in keeping his army and ports in these areas supplied and that required naval access through the Baltic, which was still controlled by the powerful Swedish Navy. Charles’ navy included some of the most modern ships of the line and frigates as well as galleys. Whereas, Peter’s navy could still only call on a smaller force of ships of the line and some frigates. However, the Russians had an extremely large force of the flat-bottomed galleys.

Precursor to the Battle

In late July of 1714, Peter finally set sail from Helsinki with a significant naval force and the intent to break the Swedish blockade that was guarding the narrow paths between the southern edge of Finland and the northwestern edge of Estonia. Most important was the area of the peninsula near Hanka.

It consists of a series of skerries that make up the Aland Islands. From there the Russian galleys, with their low drafts loaded with men, could raid and even invade parts of Sweden. Standing in the way was a blockade of ships under the command of Gustav Wattrang. The Swedish blockade force boasted 15 ships of the line, 3 frigates, and some rowed vessels including one pram under the command of Rear-admiral Ehrenskiold.

The complete Russian force that left Helsinki consisted of 9 ships of the line, 5 frigates, and 99 scampavias (small galleys). They also had a complement of 15,000 soldiers, and the plan was to occupy the peninsula and the Aland Islands from where they could launch attacks against the Swedish mainland.

In the course of the journey, Peter split his force taking the larger ships south to Reval (modern Tallinn) and leaving the 99 scampavias and troops under the command of General-Admiral Apraksin. The first task was for Apraksin to land troops on the peninsula and carry the scampavias over the isthmus to the northern end in order to bypass the blockade. He was not to engage without the support of the larger ships under Peter’s command.

Unfortunately, the sailors were beset with an epidemic upon reaching Reval. Peter was not willing to risk a major engagement with less than a full complement of sailors. Apraksin was left to his own devices in breaking the blockade.

The Battle Begins

When Apraksin arrived at Hanko, he immediately began preparations to move his galleys overland. His galleys were relatively safe from the larger ships that couldn’t traverse the shallow areas near the coast with its many shoals. However, Wattrang observed Apraksin’s intentions and sent his force of lighter ships to the north end of the isthmus to intercept any overland delivery.

This force, under the command of Ehrenskiold, entailed 1 gun pram, 6 galleys, and 3 skerry boats with a total of 67 guns many of which were large caliber. Ehrenskiold positioned his ships in a line between the peninsula and an island with his flagship, the gun pram Elefanten, positioned to engage with a broadside.

Seeing that the smaller Swedish vessels could block the shallow approaches and take advantage of windless seas, Apraksin immediately sent his fleet to run the blockade along the coast and to turn north to engage the Swedish fleet. His goal was to take his larger force and overwhelm the small Swedish ships while the large sailing vessels were forced to pull their ships by oar due to the lack of wind.

Two things went Apraksin’s way in the engagement. First, the Swedish capital ships feared being overwhelmed by the large force of galleys because they couldn’t maneuver. Therefore, the larger ships set the rowing drags to set out farther to sea. Second, with his entire force able to break the blockade, he would be able to overwhelm Ehrenskold’s smaller force by getting in close and boarding.

Despite his larger numbers, Apraksin was still outgunned as the Russia galleys typically carried only two 6 pound guns. His chance lay in his ability to swiftly close the distance between the two groups of ships and board them with his superior numbers of men (Russian galleys typically held about 200).

His first and second attempts failed, but on the 3rd attempt, he focused his attack on one of the Swedish galleys on the far left of the Swedish line and the Russians boarded it. It sank quickly, creating a gap in the line that the Russians swiftly exploited and effectively using only 23 of their scampavias to accomplish the task.

With the line broken and no support from the large guns of the capital ships under Wattrang, Ehrenskold’s squadron was boarded one after the other by the Russians, eventually getting to his ship. Each of the ships was now in Russian hands, and he was taken captive aboard his flagship.

Consequences

The Russians took all but one of the Swedish ships as prizes including their guns. The Swedes lost a total of 361 men killed and over 500 taken prisoner. The Russian losses were minimal with no ships lost and 125 men killed and 341 wounded.

The losses of the small vessels by Sweden were not nearly as big a consequence as losing the choke point into the Baltic. The Swedish fleet was therefore forced to move west of the Aland Islands to protect the Swedish coastline. The defeat and the occupation of the area by the Russians also allowed for transport ships to gain access to the Baltic coastal cities and to support Russian operations west of the Hanko.

Apraksin moved first to Abo and then onto the Aland Islands and occupied them almost without incident as the Swedish forces evacuated. The Russian navy would hound the Swedish coastline for years as a result, leading to an even larger battle at Grengam exactly 6 years later on July 27, 1720. The Russians would again deal a great blow to the Swedish Navy and a peace between the two Baltic powers would result.

Peter the Great had accomplished what no Russian ruler had ever dreamed of: A Russian navy that could support its empire and protect trade to Western Europe. This would pay large dividends for centuries to come as Russia became a major player in European affairs thereafter.

“The state which possesses only land forces, has only one hand, the state which also possesses a fleet, — has both hands” – Peter I