“Sometimes you wonder if it had been better if you had been killed instantly rather than suffer the agonizing pain caused by severe burns to the whole of one’s body.”

That statement, made by a British Spitfire pilot whose aircraft was shot down over the English countryside in 1940 gives some idea of the horror endured by those who were burned when their aircraft were attacked.

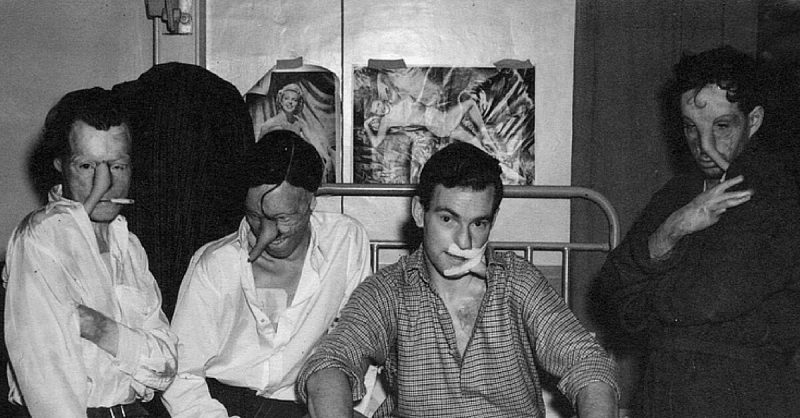

Those who survived the agony of severe burns often had to endure the mental torture of the resulting disfigurement if their burns were facial. Many of these men must have felt that their lives were effectively ruined, and they dreaded looking in a mirror.

Archibald McIndoe was appointed as consultant plastic surgeon to the Royal Air Force. A New Zealander, he worked in America before moving to England, and at the outbreak of war he took up a post at the Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead, Sussex

McIndoe was a brilliant plastic surgeon, and he pioneered many advances in surgical techniques, but he realised that apart from treating the physical consequences of severe burns it was essential to deal with the psychological effects on men who, severely disfigured by their injuries, would have to spend long periods in hospital. Some patients would undergo more than a dozen operations in the course of their recovery.

Introducing a previously unheard of degree of informality, McIndoe did away with hospital gowns in the wards, encouraging patients to wear their military uniforms. He started the famous ‘Guinea-Pig’ club for serving aircrew who had more than two plastic surgery operations. The club’s members were mainly British, but there were representatives from Canada, New Zealand and Australia, and later in the war from America, Poland, France and Russia.

McIndoe recognised that his patients needed to regain a degree of self-confidence, and he encouraged them to make excursions into the outside world. The townspeople of East Grinstead became used to seeing badly disfigured patients on the streets – it became known as ‘the town that didn’t stare’.

The lack of formality in the wards even extended to having barrels of beer available. Inevitably, some of the young men flirted with the nurses, and McIndoe turned a blind eye – it was all part of his policy of treating the person, as well as the burns.

Later, many of the men also served in other capacities in RAF operations control rooms, and occasionally as pilots between the surgeries. Those unable to serve in any capacity received full pay until the last surgical operations and only then were invalided out of the service. McIndoe also later loaned some of his patients money for their subsequent entry into civilian life.

At the end of the war, the Guinea Pig club had 649 members. In 2003, there were around two hundred survivors; by 2007 there were 97 (57 in Britain; 40 elsewhere in the world), their ages ranging from 82 to 102.

The last annual reunion was held in 2007, and attracted over 60 attendees, but in view of the frailty of many of the survivors the decision was then taken to wind the club down. By April 2015, there were believed to be 29 survivors.