“She wanted to disturb the British supply lines like a wolf breaking into the sheepfold; doing as much damage as she could while avoiding superior enemy naval forces.”

– Official German archives on the SMS Emden

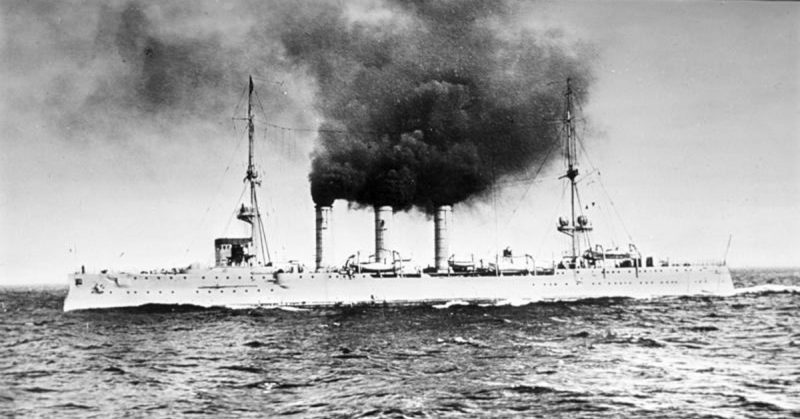

In 1906, the German Imperial Navy commissioned a second Dresden class light cruiser and named it the SMS Emden. Under the command of Captain Karl von Muller, the Emden went on a defiant, “piratical” streak throughout the outbreak of hostilities against the Allied forces, a few weeks after WWI was declared.

The Emden dislodged Allied power by first intercepting the Greek Pontoporros, which carried supplies and ammunition. It took the capture of a steamer and 25 civilian vessels, and more than 30 Allied ships set ablaze for the cruiser to earn notoriety, a fearsome reputation, admiration, and respect.

Although the expedition was short-lived, the extraordinary feats accomplished by the lone cruiser successfully commanded the war in the South’s attention, and then eventually the whole world’s.

Remarkable Exploits

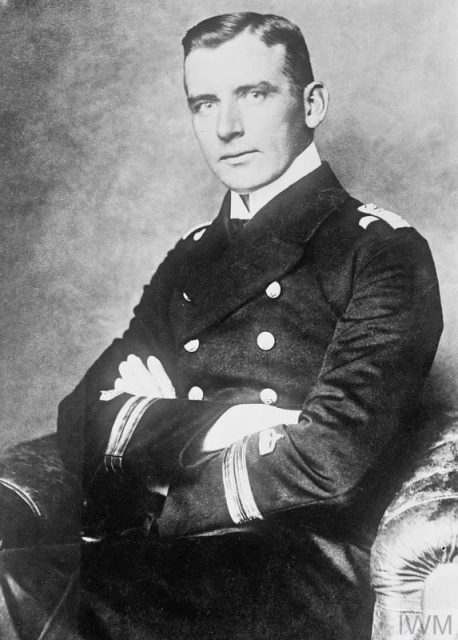

Karl von Muller, along with 17 other officers and a crew of 343, manned the Emden throughout her journey. An underdog in terms of weaponry, defense, and design – she baffled enemies by “striking out of nowhere” and quickly disappearing before they could react.

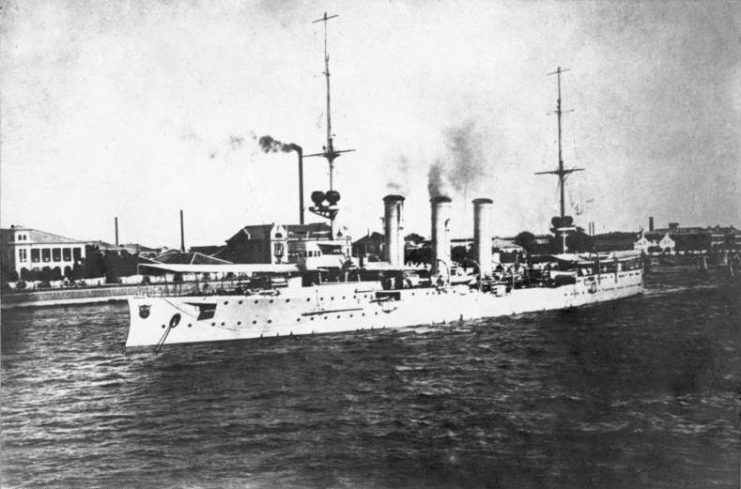

Size was obviously no deterrent to war. Von Muller’s expertise and tactical genius, which largely helped the Emden to evade capture, was due to his being a seasoned naval officer. His gallantry and fair treatment of all, even his prisoners, earned him respect among his men and his enemies. The Emden, however, only came under his command in 1914, just as it was assigned to a Chinese territory called Qingdao, then leased to the Germans.

Von Muller’s cleverness was already evident prior to the outbreak. When the war between the great powers became inevitable, he pulled out the Emden off the Qingdao base, smartly averting the joint Anglo Japanese assault on the Germans.

After the war broke out, Von Muller charted a course for the Mariana Isles, where the whole German East Asia Squadron under Admiral Maximillian von Spee was preparing for their trip to South America. He suggested to Spee that the Emden stay behind to disrupt British shipping. The admiral agreed.

Remarkable Exploits

Before the interception and seize of the Pontoporros when the war was only a week old, the Emden captured and acquired the Russian mail steamer Ryazan and overhauled it. This was Germany’s first captured ship in the war. While escorting it back to Qingdao, the Emden managed to avoid a fleet of French warships. Although relatively small in the grander scheme of the war, this accomplishment is seen by experts as an ominous sign of the cruiser’s remarkable defiance.

Beginning September, the Emden had already plundered 15 British trading ships in just a few days. Panic gripped the Indian ocean and even civilian voyages were halted for fear of being captured or looted. Muller used this to the Emden’s advantage, and then began widening the expedition to include shore targets.

Soon they entered Madras harbor in India and bombed the massive oil tanks of the Burma Oil Company with a 125-round barrage, setting them ablaze and destroying a vessel in the harbor. This naturally fueled more panic. The Emden, by this time, was considered more than just a cruiser commissioned for war. Enemies, neutral parties, and civilians treated it as a pirate ship, but not always so negatively.

The British were stunned by the attack, and before they could react, the Emden disappeared. Von Muller was also keen on minimizing civilian or unrelated casualties, a fact testified by several captured or imprisoned parties he encountered.

Still, the Brits were embarrassed, and as a result, reduced the number of ships in the region to prevent destruction or capture. During that time, the Emden’s impact reduced the shipping in the Indian Ocean to an estimated 60% – impressive for a single, light cruiser.

Not long after, the Emden made her way to Diego Garcia, a British colony administered by Mauritius and situated 1700 km off the tip of India. Von Muller again ran with the risk of initiating a battle, thus preparing to attack the unsuspecting enemy.

To his amazement, the Emden was welcomed, for no news of the war had reached its shores. Repairs were done, coal was restocked, the men rested and fed. For his gratitude, von Muller put his crewmen to work by fixing a local’s boat. Repainted and reinforced, the Emden left the harbor bolder than ever.

Towards the end of October 1914, von Muller’s major encounter was in the Battle of Penang in Malaysia, still under the control of the British colony. The Russian warship Zhemchug was there, docked for repairs.

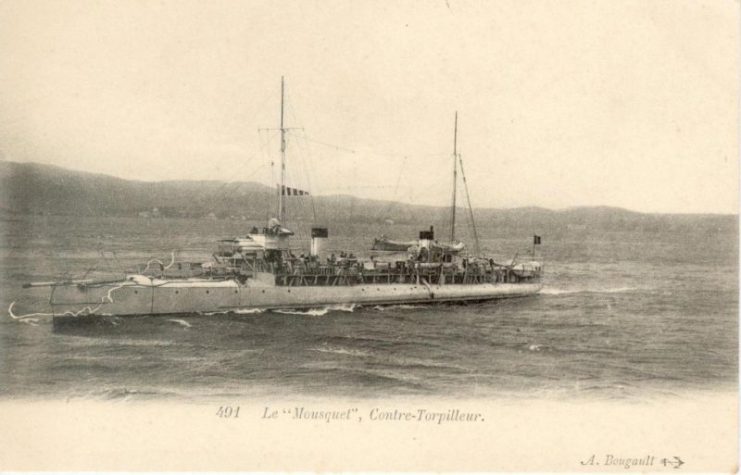

The Emden entered the harbor disguised as a British cruiser, complete with a fake smokestack – a recurring tactic von Muller enforced throughout encounters and evasions – and sank Zhemchug with her torpedoes and broadside guns. Before leaving Penang, the Emden also sank Mousquet, a French destroyer.

Von Muller didn’t believe luck could hold out forever even after the victories, but he pushed the Emden through to her next goal.

She is Finished, But She Does Not Sink

After Penang, the Emden set sail for Direction Island in between Australia and Sri Lanka. Von Muller’s next objective was to disable a British telegraph station vital to the strategies of the Allies. Upon arrival, he sent a shore party under first officer Hellmuth von Mucke to bring down the radio mast and disable the communications. There was no resistance; the locals refused to interfere upon knowing von Muller was behind the instruction.

Gallant as ever, von Muller promised to spare a nearby tennis court. Unknown to him, a distress call had already been sent out. Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney was nearby and would arrive at the scene three hours later.

Von Muller abandoned the shore party and directed his focus to the Australians. The Sydney was far superior in strength and defense, but was amazed at the Emden’s initial barrage, not expecting her to be capable. However, one round was all she could do before the Sydney tore into her.

By sunset, von Muller ordered the severely damaged Emden onto a sandbar to avoid sinking. She had already been hit more than a hundred times during the first 90 minutes of the battle. Naval warfare rules prevented the Australians to ceasefire, not until her colors were out of sight. Von Muller then instructed the flag to be hauled down to stop the battle.

With his remaining men, Von Muller surrendered.

Things Take a Turn: The Shore Party’s Journey

It wasn’t quite the end for the Emden’s sons. Von Muller was held as a POW in Malta until he was exchanged and returned to Germany. His crewmen were taken to a POW compound in Singapore, run by the Brits and were later given the chance to escape by a mutiny started by the 5th Indian Light Infantry.

Von Muller was promoted to full captain, awarded the Iron Cross 1st class along with his other officers, and was hailed a war hero. His crewmen were also awarded Iron Crosses 2nd class when they returned.

His shore party’s journey back to Germany, however, wasn’t as easy. Von Mucke, the first officer, assumed command and prepared the others for a landing party after the attack of the Emden, but it never came. The Australians left.

The men then went aboard the last vessel ashore – a very old schooner named Ayesha. Loading Ayesha with food and other supplies, the Germans sailed for the high seas again. They relied on the rainwater they could save for hydration and on the shifting winds for propulsion. They eventually anchored on Padang, Indonesia on December 27th. Indonesia was a Dutch colony, which by then was neutral.

They left the following night and sailed once again to their unknown fates. They avoided Allied steamers and persisted through harsh weather across the Indian ocean, until they luckily caught up with the Austrian streamer, Choising. The sailors were welcomed aboard. Von Mucke would later say,

“The loss of the brave little ship touched us deeply. Although our life on board had been anything but comfortable, we nevertheless fully realized that it was to the Ayesha we owed our liberty. For nearly a month and a half she had been our home. In that time, she carried us 1709 nautical miles. We all stood at the stern railing of the Choising and watched the Ayesha’s last battle with the waves.”

The sailors were then informed that the Ottoman Empire had joined the war and were their allies. The Choising went for the Bab-el-Mandeb strait, guessing and hoping that the Ottomans still had control over Southern Arabia.

They arrived near Hodeida and made their way through the desert. Soon, they encountered a group of armed nomads, whom they desperately tried to suggest their alliance to. Von Mucke recounts pointing to the eagle, and when that didn’t seem to mean anything, he pointed at the head of the Kaiser, which was met with loud response. The men eventually made out the words “Aleman” from the nomads, which they enthusiastically shouted back.

They were escorted safely straight to Hodeida, where the Turkish governor fed and supplied them. They marched out onto the desert again but were forced to return when some of the men acquired illnesses. The only other way for them to get to Europe was to get to the Red Sea, which was blocked by the English.

After running through the blockade, they made it to Al-Qunfudhah, from where they started their journey towards Jeddah. By this time, it was already March. Through their journey, a British-paid Bedouin group besieged them for two days. The men had to hope for the best by taking cover behind dead camels or makeshift sand trenches until a Turkish group from Mecca saved them.

They soon followed the Hejaz railway to Damascus, then Aleppo, and finally to Constantinople. They arrived home on May 23rd and was announced by Admiral Wilhelm Souchon in typical military form, “I report the landing squad from the Emden, five officers, seven petty officers, and thirty men strong.”

Small Foe, Big Admiration

Hong Kong, the place the Emden mostly frequented during her expedition, found it difficult to regard the Germans as the enemy after the war forced them apart. Months before, the Emden had anchored on the Victoria Harbor, warmly welcomed by both local dignitaries and fellow German expatriates.

This silent film titled “Sea Raider” was even made in Australia about the Emden’s exploits.

Perhaps it was the same reluctance that allowed Hong Kong to herald the Emden throughout her journey. Citizens were undeniably enjoying her daring exploits across the hostile waters of the Indian ocean. Even British seamen merchants, who were aboard the captured Indus and were sent safely back to port, could not resist advertising how the Emden crew was using their soap, after recovering their cargo.

The fiasco the Emden left behind for her enemies were entertaining for those who regarded the Germans as friends. As a result, Hong Kong news outlets were littered with cheap propaganda against them. And, although Hong Kong funded and reinforced the war, a noticeable affection for the Emden remained among the public.

Von Muller’s humane reputation and gallantry, alongside the victories of the Emden and the persistence of Von Mucke’s landing party, made headlines across the world for a time. The word “Emden” has since been included in two languages. In Tamil, “endema” is used to describe someone clever or sneaky. In Malayalam, “emendem” means great.

The China Mail, in a prolonged November editorial, expressed admiration for Von Muller in a time of war, saying “He is making history because he is doing what hardly anyone thought could be done.”

Read another story like this one – CSS Alabama – Best Commerce Raider in History

The remains of the Emden were looted and prized for trophies. The rest went to scrap. Naturally, there are now movies about her journey.

Von Muller died of malaria complications in 1923.