War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

When his draft notice arrived in 1969, Ron Bogg was attending Lincoln University and close to graduating. There may have been an opportunity for him to delay his induction into the military through an educational deferment; however, Bogg explained, he chose to enter the service and perform the duty for which he was called.

“It’s basically patriotism,” Bogg said. “I didn’t want to go (to Vietnam)—I know very few people that did.” He added, “It was our duty to go and some never came back home.”

On February 11, 1969, the draftee traveled to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, where he spent the next few months completing his basic training followed by advanced training to become a heavy equipment mechanic.

“When I took the testing prior to my induction, the scores, I was told, indicated that I was highly proficient in mechanical abilities while my worst scores were the ones related to infantry, which was a relief,” Bogg chuckled.

Upon graduating from Army mechanics school, the newly trained soldier received orders for Vietnam and “about a week or so later,” was on an airplane bound for his new overseas assignment. Within days of his arrival in Vietnam during the summer of 1969, Bogg received orders for a unit near Phu Cat, but sought the assistance of the Red Cross to get this appointment changed.

“I told the Red Cross that my brother, Carey (Bogg), was serving with a unit in Vietnam and he was scheduled return to the states in a few weeks,” said Bogg. “The Red Cross was able to help me get orders for Company D, 864th Engineer Battalion located near Ban Me Thuot—my brother’s unit.”

Bogg soon met up with his brother, who spent the final days of his service in Vietnam introducing him to the operations of the unit. Prior to his brother’s departure, his brother gave him his M-14 rifle to carry in addition to his flak jacket and other equipment.

Their compound was located near Montagnard villages—an indigenous people of the Central Highlands of Vietnam. According to an article by Amy Fabry accessed through the Defense Media Network, “It is estimated that 40,000 Montagnards served with the U.S. military as soldiers, scouts, and interpreters, and roughly 200,000 Montagnard people perished by 1975.”

Bogg said, “They were super good people, in my opinion, and whenever you went into one of their villages it was like stepping back in time.”

As part of the duties he assumed for his brother when he left Vietnam, Bogg began transporting the Montagnards back to their villages in the evenings after they had spent all day working in various capacities on the Army compound.

Additionally, Bogg explained, he performed duties that included repairing and maintaining the company’s vehicles and was afforded the opportunity to engage in activities ranging from cutting pylons for bridges to learning how to weld.

“We were out in the middle of the jungle and the Vietcong could have overrun our compound anytime they wanted because we were down to around 80 soldiers, but fortunately that never happened,” he said. “It was a pretty laid back bunch in our company but we did our jobs and did them well,” he affirmed.

After nearly 11 months near Ban Me Thuot, Bogg and the soldiers of Company D closed the compound, loaded their equipment on trucks and began a convoy to join the remainder of the 864th Engineer Battalion on an outpost called “Whiskey Mountain”—a “large hill surrounded by rice paddies and jungle”—near Phan Thiet. It was at this new location, Bogg said, that the enemy “really bothered us.”

During the convoy to their new duty location, the veteran explained, his company encountered enemy resistance that would essentially define the remainder of his stay in Vietnam.

“On the convoy, I rode on a truck with a friend of mine, David Marine,” said Bogg. “I took a picture of (David) with my camera and he asked me to take some more. I told him there would be plenty of time for that later.” With faint hesitance, he added, “We were ambushed shortly after that and David was shot … he died in my arms.”

On another occasion, Bogg was with a group of soldiers on a 5-ton truck traveling in a convoy down a road on Whiskey Mountain when they were hit between the rear wheels with a rocket-propelled grenade. As the veteran recalled, the truck’s driver was able to “hang onto the steering wheel all the way to the bottom of the hill,” making it to a safe location where the vehicle could be repaired.

“That explosion is the reason I wear a hearing aid today,” Bogg noted.

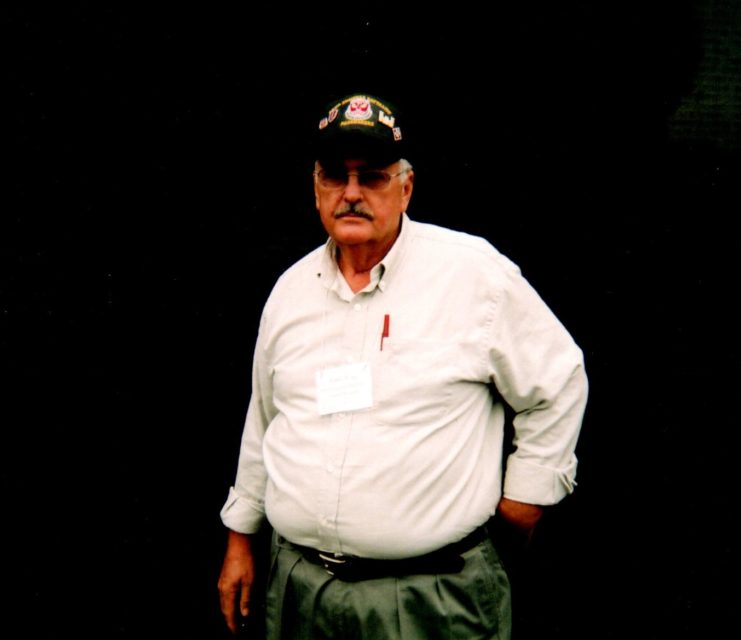

His tour of duty in Vietnam ended in September 1970, at which time he returned to Mid-Missouri. In the years after the war, he married, raised children and enjoyed a lengthy career as the owner of Bogg Steel and Stove. Though now retired, he is a life member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and serves as senior vice-commander of the local Disabled American Veterans post.

When asked about the most profound moments of the time he spent in the Army during the Vietnam War, Bogg affirmed that his thoughts frequently center on David Marine, and his efforts to provide a sense of closure for the young soldier’s family.

“Several years ago, I was able to track down David Marine’s mother in Tennessee,” Bogg explained. “When I talked to her on the phone, she said that she was in bad health but I remember her asking if her son had suffered when he was killed. I told her ‘no,’ that he had went fast. I then sent her the last picture I took of him but never heard from her again.”

He gently added, “This is the kind of thing that happened to us (in Vietnam) and it just stays with you.”