The first impression was being in an infinite desert of ice…. There was nothing but a flat patchwork maze of ice floes in every direction.

Navies for centuries have been interested in operating in Arctic conditions. Whether it be in search of the northwest passage or whether to maintain a supply line to the Soviet Union during World War II, there has always been a desire and need by those afloat to conquer the frozen north.

Surface ships had tried, and inevitably failed, to reach the highest latitudes. But after the advent of submarines, people began to imagine that perhaps the North Pole was attainable from below the surface. It was only well into the 20th century that this notion became a practical reality.

Operating a submarine under polar ice caps is simple in concept but highly dangerous. The ice below is uneven and often very thick. In the early days of submarines, there were no sonar systems that could detect where the ice was in relation to the boat. If there was an emergency that required an emergency surfacing, it was likely that the vessel would crash catastrophically into the ice.

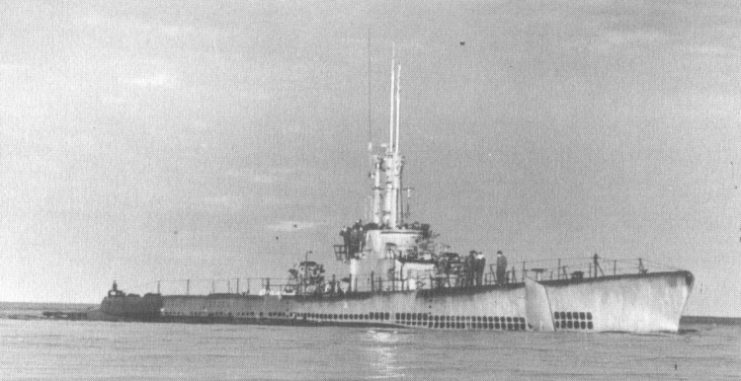

By the 1930s, technology had improved enough to make the dream of polar submarine operations plausible, albeit still dangerous. In August 1931, the first submarine expedition to operate in the Arctic launched. The Australian explorer and geographer Sir Hubert Wilkens acquired the submarine O-12 from the U.S. Navy and refitted it as the Nautilus.

The submarine’s new design was specific for ice operations, complete with an escape tube topped with a saw to cut through the ice pack and a mechanical probe to gauge the depth of the boat relative to the ice. Both were not fully tested. The expedition, however, was cut short by damaged diving planes.

Still, the submarine ran successfully under ice, even reaching 82 degrees north. It was obvious that with improved technology, submarines could reach the Pole.

The next major submarine polar expedition was the U.S. Navy’s Operation Nanook in 1946. While the mission was not meant specifically to reach the North Pole, its contributions were significant toward the development of Arctic naval operations. New equipment was tested, and ice-sounding gear was improved which enabled a watershed moment in submarine history 12 years later.

In 1958, the U.S. Navy’s first nuclear-powered submarine, also named Nautilus, was given a secret mission code named “Operation Sunshine.” Its purpose was to reach the North Pole.

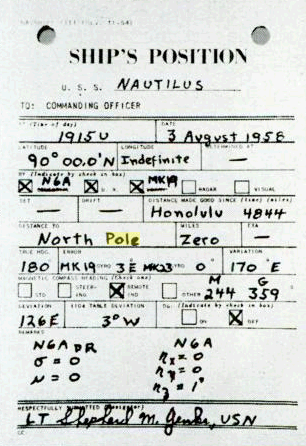

The submarine left Pearl Harbor on July 23, 1958 and sailed to the Bering Straits. From there, Commander William R. Anderson gave the order to dive and make for the Fram Straits, crossing the Pole en route.

One hundred and sixteen men sailed on into unknown waters until at 11:15 p.m. on August 3, 1958, Anderson announced to his crew, “For the world, our country, and the Navy – the North Pole.”

Their secret mission was soon not so secret. For the deed, the submarine received the first peacetime Presidential Unit Citation. The submariners of the Nautilus were feted in New York City with a ticker tape parade. One crewman recalled feeling like a rock star. Today, the Nautilus has been preserved at the Submarine Force Museum in Groton, Connecticut.

Several months later, the U.S. Navy made another mark on naval history. On March 17, 1959, the submarine U.S.S. Skate managed to surface through gaps in the ice at the North Pole.

It was a terrifying moment since the submarine had to negotiate between ice floes that could easily sink the craft. James F. Calvert, the commanding officer of Skate, was relieved when his boat emerged safe and sound. He then exited the submarine.

Later, Calvert recalled the awe of the moment. “The first impression was being in an infinite desert of ice…. There was nothing but a flat patchwork maze of ice floes in every direction. Directly before us the slender black hull of the submarine contrasted with the deep blue of the calm lake water and the stark white of the surrounding ice.”

He and his crew were met almost immediately by a polar bear, which had probably never seen a nuclear-powered submarine before.

Skate’s crew planted the American flag and scattered the ashes of Sir Hubert Wilkens into the Arctic winds.

In the decades that followed, other countries followed suit – the Soviet Union in 1962 and the United Kingdom in 1971. By the early 21st century receding ice caps had led to the emergence of new waterways and access to resources, placing the region into greater geopolitical significance.

Joint allied operations organized by the United States Navy have become a biennial occurrence. Dubbed ICEX, the five-week exercises feature under-ice weapons testing, the collection of scientific data, and diving operations.

The 2018 exercises were conducted out of a temporary base named Camp Skate. The base, which is multinational in flavor with representatives from several NATO countries, contains kitchens, a medical bay, lavatories, and warm storage for items that cannot be exposed to the polar environment. The base is also equipped with a diving shelter.

Diving is perhaps the most punishing of all the Arctic exercises. In the 2018 operation, divers from the Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit Two, Underwater Construction Team One, and Coast Guard took dips below the ice to recover training torpedoes which contain important testing data.

The divers are specially trained for the work since the ice and water temperature, which is just below 29 degrees, make it especially dangerous.

But the highlight of ICEX is the thrill of watching massive Los Angeles-class and Seawolf-class fast attack submarines surface through desolate ice fields.

Videos of the event are wildly popular and reveal that some cold weather maintenance tasks, like scraping ice off your vehicle, are common to submariners and suburbanites alike. But instead of plastic ice scrapers, such as the ones you might use on your Ford, the crews of these submarines use large steel crowbars to clear ice from their conning towers.