From spiked German helmets to steampunk-looking body armor, World War I saw its fair share of strange uniform choices. The conflict was fascinating, as it was essentially a meeting point of new and old, with horses charging into machine gun fire and pilots in aircraft throwing objects at each other. Similarly, the way troops were dressed was more appropriate for this new era of unromantic devastation, yet it still incorporated principles from the past.

Popularizing the trench coat

The trench coat was a useful and practical piece of clothing that was optionally worn by officers during the Great War. It was adapted from the greatcoat, which was found to be too heavy and impractical in the wet conditions of the trenches.

Trench coats were constructed from a lighter, yet water-repellent material to keep officers dry, and they featured large pockets to store maps and documents. As well, adjustable wrist straps kept water from running down one’s forearms while using binoculars.

The supply of the more practical trench coat was made possible by civilian tailoring firms.

Over one million civilian suits were given to troops returning home

When World War I ended, the British Army gave almost 1.5 million suits to soldiers who were returning home. Why? By law, a soldier wasn’t permitted to wear their uniform for more than 28 days after they were discharged.

Those returning home were given a plainclothes form, which they used at dispersal centers to receive either a suit or a clothing allowance. They were also given a pay advance, a ration book that was good for a fortnight and a train ticket home.

Turbans were a common sight on the Western Front

During World War I, Britain’s colonies – namely India – made huge contributions to the war effort, but this is often overlooked.

At the end of 1914, a third of the British forces fighting on the Western Front were from India, as part of the Indian Expeditionary Force. Sikh soldiers wearing turbans were a common sight, and while this was a proud tradition, it signaled their “lesser” colonial status, given racial attitudes at the time.

Khaki was first used in India

World War I saw an emphasis on remaining hidden from the enemy, rather than going toe-to-toe with them in brightly-colored uniforms. Camouflage and smokeless guns were used to help troops stay out of sight.

However, did you know khaki camouflage actually originated in India? In the late 1840s, Harry Lumsden took his Corps of Guides to a riverbank with a supply of white cloth purchased from the market in Lahore. The fabric was soaked in mud, allowing them to blend in with the dusty environment.

Britain sourced khaki dyes from Germany

Ironically, the dye used in khaki uniforms was secretly imported from Germany during the First World War.

Prior to the conflict, Germany was a leading manufacturer of synthetic dyes. By 1913, the country was exporting over 20 times more dye than Britain.

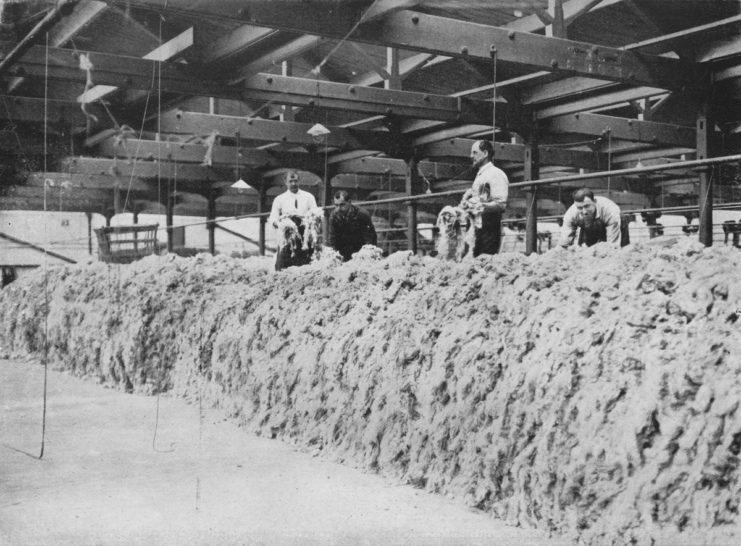

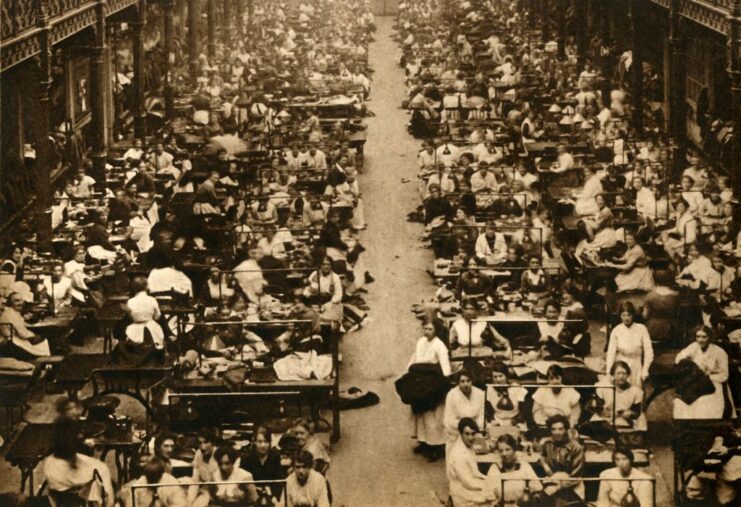

Contracting civilian firms to produce uniforms

Logistically, Britain wasn’t prepared for a conflict on the scale of the Great War. In the first few months, the War Office only had enough uniforms to cloth existing service members and frontline troops serving with the Territorial Force. The recruitment of a quickly increasing number of soldiers overloaded the military’s own factories.

This problem was solved by contracting civilian tailoring firms to produce uniforms on an enormous scale – an arrangement that benefited both the military and suppliers.

An allowance was given to officers who couldn’t afford a uniform

At the start of World War I, officers were usually recruited from the upper class, which meant they could easily pay the expenses associated with a new uniform. However, as the conflict dragged on, the losses of these servicemen forced the military to recruit from progressively wider social classes.

Many of these men were unable to pay for their uniforms, so the British Army subsidized the costs, to maintain sufficient recruitment. Unsurprisingly, a gap developed between the officers of different social classes.

Official knitting patterns were introduced to regulate designs

The War Office’s own supply of uniforms was supplemented by civilians, who knitted items of clothing and creature comforts for the men serving on the frontlines. However, this well-meaning practice quickly started running out of control, with increasingly garish items arriving to the troops.

The government was, understandably, worried about this, so it introduced official guidelines to be followed by knitters. The variety of garments sent across the English Channel centered around official knitting patterns.

‘Kitchener blue’ supplemented khaki

Supply issues caused by Germany’s aforementioned dominance in the production of khaki dyes forced Britain to turn to some less than ideal options. The War Office began supplying soldiers with anything it could, including 500,000 blue Post Office uniforms and 500,000 greatcoats. In addition, the War Office also ordered a huge amount of clothing from the United States, meaning that a few poor souls were dressed in scarlet and blue parade uniforms – not exactly inconspicuous.

These filler uniforms were collectively called “Kitchener blue.”

Conscientious objectors were forced to wear uniforms against their will

After being conscripted into military service, conscientious objectors often refused to don a uniform. As they were regarded as enlisted men, they could be punished by law and were commonly subject to violence and humiliation.

More from us: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Experiences During the Battle of the Somme Influenced ‘The Lord of the Rings’

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

Conscientious objectors used different means to protest against the military – some refused to undress for medical examinations while others refused to wear a uniform. In these instances, it wasn’t uncommon for them to be pinned down and forcibly looked over or dressed.