One of the most formidable military infantries from the Middle Ages was the Swiss pikemen. Despite being a small contingent with little in the way of weaponry, these soldiers defeated their opponents with speed and ingenuity. They were both feared and respected across Europe, and they brought warfare back to the people, as opposed to the nobility who had taken it for themselves.

Living outside of noble rule

The origin of the Swiss pikemen dates back to the 1300s, when Switzerland split from the Holy Roman Empire. Its cantons declared the Swiss Confederacy, wherein each person was free to live outside the rule of an overarching leader. At the time, they were the only European enclave to have such a distinction.

The split angered Leopold I, Duke of Austria. In 1315, he sent the Hapsburg Army into Switzerland to force the cantons to return to the Empire. He thought it an easy victory, as the Swiss were peasants without much in the way of armor or weaponry. However, he was greatly mistaken.

On November 15, 1315, the peasants of Schwyz, Uri, and Unterwalden attacked Leopold’s army, charging toward them with pikes. This tactic made up for their lack of defense. Their resulting victory allowed for the consolidation of the three cantons, which would form the core of the Swiss Confederacy.

The attack, known as the Battle of Morgarten, is credited with changing the way warfare was fought during the Middle Ages. It also allowed the Swiss to begin making a name for themselves as the fiercest fighters in Europe.

The Battle of Arbedo

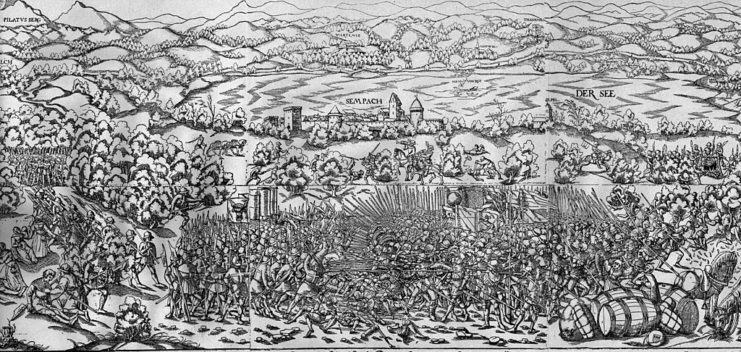

The Swiss would go on to use pikes alongside other weaponry during battle throughout the 14th century, including during the Battle of Sempach on July 1386 against Leopold III, Duke of Austria. However, they didn’t opt to make pikes their weapon of choice until the 1422 Battle of Arbedo against the Milanese.

The Swiss were outnumbered five-to-one. After several advances, the Milanese dismounted, held their lances like spears, and charged toward the Swiss contingent, which had formed a defensive circle. The lances outreached the halberds used by the Swiss, and the result was a victory for the Duchy of Milan.

In the battle’s aftermath, it was decided the halberdiers would guard the banners and dispatch any enemy forces that broke through the preliminary pike infantry. The overall formation would start with the vanguard (vorhut), followed by the body (gewaltshaufen) and the rearguard (nachhut).

The Swiss pikemen

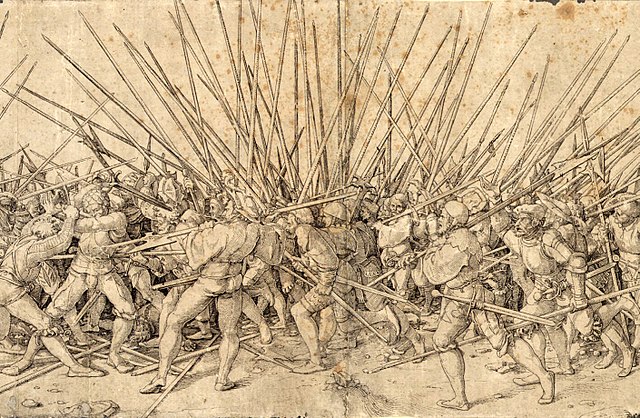

The force consisted of approximately 8,000 men. Each column in the formation was interspersed with pikemen, with halberdiers and double-handed swordsmen at the center. The contingent was covered by crossbowmen and hand-gunners, who did the double-duty of distracting the enemy’s artillery and protecting against attack.

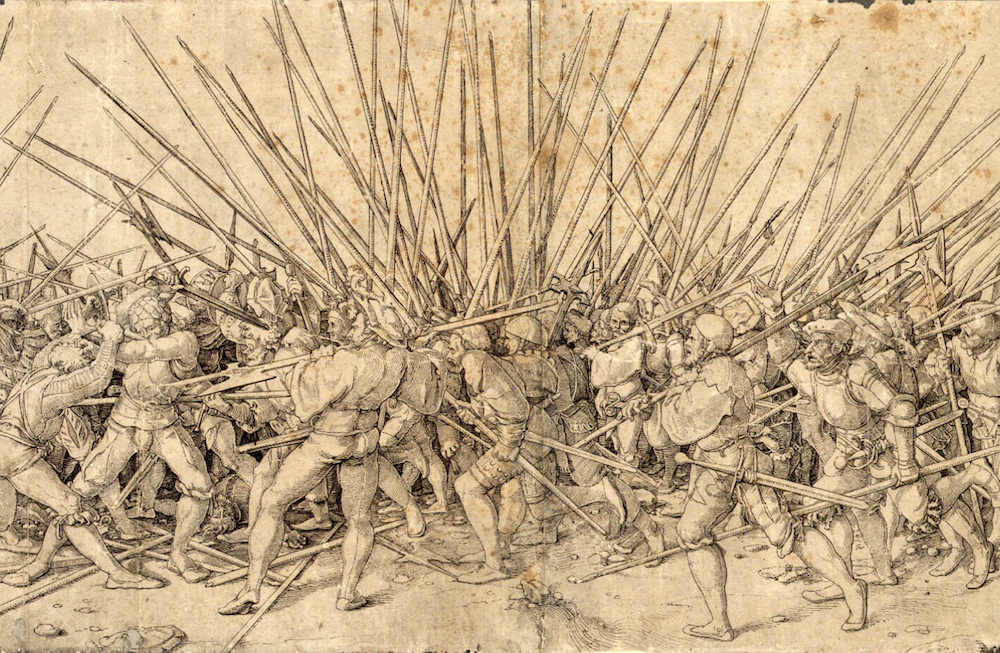

These formations provided support for the entire infantry, in case one column fell to enemy fire. If they needed to stop for any reason, the columns quickly converted into a hedgehog formation, creating a compact square of pikes before charging forward.

If the enemy didn’t back down, the pikemen were positioned to attack and break their lines. They were an impenetrable wall no one could overcome, similar to the Hoplite shield of Ancient Greece. Using their swords and daggers, they would then work to overwhelm their opponents and win the battle.

Success in battle

The key to victory for the Swiss was to constantly advance, regardless of what they faced along the way. This method afforded them many victories. They saw two successes against the Burgundians and many against the Holy Roman Empire. The most notable was the aforementioned Battle of Sempach, which led the Hapsburg Dynasty to sign a 50-year peace treaty with the Swiss Confederacy.

In August 1444, the Hapsburgs again tried to assert their dominance. The emperor teamed up with King Louis XI of France, who sent 30,000 men into Switzerland. The army ran into a unit of between 1,200 and 1,600 pikemen. While Louis won the battle, he called off the invasion, retreated back to France, and made an alliance with the Confederacy.

The way in which the Swiss pikemen attacked was incredibly brutal and without mercy. While much of their success is attributed to this, it’s also the result of their use of land. Swiss generals would use their knowledge of the terrain to their advantage, allowing them to surprise enemies. This often meant rolling boulders down hills in a surprise attack, before charging in on foot.

Swiss mercenaries join European army ranks

Before long, word of the Swiss pikemen spread across Europe. Rather than fight against them, most rulers opted to hire them as mercenaries. This was especially prevalent in Italy and France during the 14th and 15th centuries.

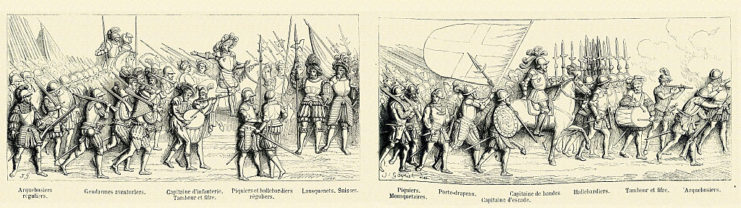

The makeup of Swiss mercenary units was different from their cantonal counterparts. They typically opted to form two columns, as opposed to the cantonal three. They also stood side-by-side, forming the center of the infantries they served.

While the majority of Swiss mercenaries were pikemen, the term was used as an overarching catch-all term for the troops. It referred to Swiss troops using all sorts of weapons, including crossbows, handguns, and other artillery weapons, though these were used far less than pikes and halberds.

Mercenary involvement allowed for numerous victories, including the 1494 conquering of Naples and the 1525 conquering of Milan by the French. Their lack of mercy on the battlefield instilled fear in those they fought against, so much so that the Valois King of France believed it impossible to enter combat without Swiss pikemen at the core of his army.

The Landsknechts

After 1490, European nations began to adopt the pike system. Imitation units sprung up across the continent, with the most notable being the Spanish Tercios and the even more formidable German Landsknechts.

The Landsknechts became the Swiss pikemen’s primary enemy, as they began to fill the mercenary ranks they once held. They also took care to study the battle tactics of the pikemen, surpassing them with their usage of the Zweihänder, a two-handed sword used to break through opposing pike formations.

The pair’s rivalry was especially evident on the battlefield. While the pikemen managed to maintain an edge against their opponent, the combat between the two was often described as particularly savage, especially during the Italian Wars of 1494 to 1559.

The end of Swiss mercenaries

The end of the Swiss pikemen came after numerous losses during the Italian Wars. While they saw a close defeat at the Battle of Marignano in 1515, their biggest came in 1522 with the Battle of Bicocca. The Swiss pikemen were serving the French and were up against forces of Tercios and Landsknecht.

The battle resulted in bloodshed. The Swiss repeatedly tried and failed to break the opposing defensive position without the use of artillery or military support, leading to slaughter at the hands of enemy arms and artillery fire. It was the first time they’d suffered such an immense loss without inflicting major damage.

The introduction of gunpowder was the nail in the coffin for the Swiss pikemen. After the 16th century, they adopted tactics and formations similar to those armies in which the mercenaries served across Europe. This meant taking a normal position in the battle lines of other infantry units, as opposed to their usual stance.

Their best showings during this time came alongside the French Army. Their service was commissioned by the monarchy during the French Wars of Religion, and they showed exceptional prowess during the Battle of Dreux in 1562, during which a contingent of Swiss pikemen held off the Huguenot army until the Catholic cavalry arrived.

Laters years and existence in the modern day

Swiss soldiers continued to serve as mercenaries with a number of European armies between the 17th and 19th centuries. However, they had to contend with changes to their drills, weapons, and tactics.

More from us: Athenian Military Might: How Does It Stack Up In The Ancient World?

Since 1859, only one pikeman mercenary group has been allowed to exist, the Vatican’s Swiss Guard. The unit has been tasked with protecting the Pope for the past five centuries and represents the official army of the Vatican. They dress in colorful uniforms believed to have been designed by Michelangelo, who was inspired by their heyday during the Middle Ages.