After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the US military would not allow the Rose Bowl game to be played in Pasadena, California. So the game, to be played between Duke and Oregon State, was moved to Durham, North Carolina.

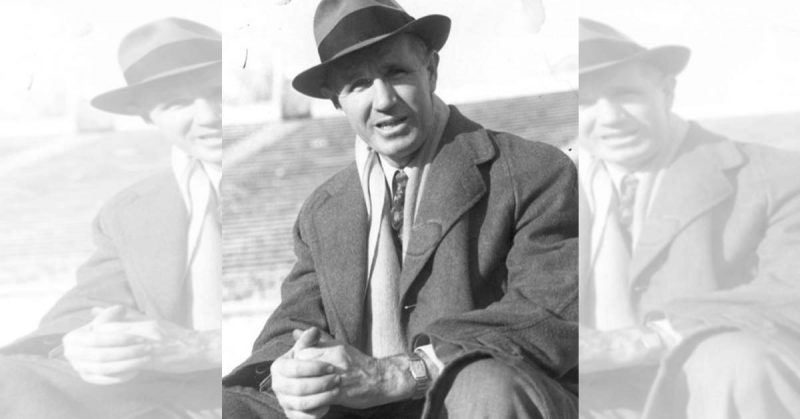

The Duke football coach was Wallace Wade. He organized the game in around two weeks. Part of his job was convincing his players to go along with the change.

The players, though, had been looking forward to the Pasadena trip. Hollywood stars had invited them to visit, and they were excited about traveling the country and seeing the sights out west.

Another two weeks in Durham was not enticing to the Blue Devil players. Many would soon be joining the military and might not make it back for Christmas for years.

The first vote of the players was against playing the game by a margin of 25-2. When Wade offered to give them six days off for Christmas, they still rejected it, 17-10. Eventually, Wade convinced enough to play with a vote of 15-12.

Brian Curtis has a new book called “Fields of Battle” that talks about Oregon State’s 20-14 victory on January 1, 1942. The book tells little-known facts about the game but continues from there to tell the story of the players as they served in the war and then on into their post-war lives.

“It started out as an article for Sports Illustrated, turned into a book about the Rose Bowl game in Durham, became a World War II book and ended up, I think, as a people book,” Curtis said.

Wade took the blame for the Blue Devils’ loss in that game. He was distracted with the preparations for the game. He also said that there were not enough distractions for the players who didn’t want to be stuck in Durham over Christmas break. Wade reduced the number of practices and sent the players home for Christmas.

More than seventy players and coaches from that game went on to serve in the US armed force during the war. 29 of the 31 players on the Oregon State team went to the war and unfortunately, four of them died in it.

Curtis had expected to interview players from the team, but there were few of them left. He was able to talk to wives, children and siblings to learn more. Unfortunately, most of them said that their loved one had never discussed their experience in the war.

Curtis turned to declassified military documents. A lot of the time, he found information that family members did not know.

“Telling them about their loved one’s war experiences and their heroic service, was one of the most rewarding aspects of the project,” Curtis said.

Wade, at 52 years of age, fought at Normandy, on the Siegfried line, in the Battle of the Bulge and the crossing of the Rhine. He received the Bronze Star and a Croix de Guerre with Palm from France.

He returned to coaching at Duke after the war, but it wasn’t the same. After facing death in Europe, football didn’t seem as important. Also, after being away for five years, the game had changed in ways he didn’t like.

Jim Smith, who played end for Duke, is the only living player from that game. In the war, he survived a kamikaze attack in Okinawa. He currently lives in Louisville, Kentucky and plays golf three times a week, The News and Observer reported.

Curtis and Smith visited Durham in November. Smith spoke to the team and was recognized at halftime.

Someone once asked Wade if the loss to Oregon State or the loss to USC in the 1939 Rose Bowl was the biggest disappointment of his life. He replied that the biggest disappointment of his life was not getting to be one of the first people to land at Normandy.