History has many hidden corners and blind spots, places where the official record is so swayed by ideological bias that historians of the future will be hard pressed to discern what actually happened.

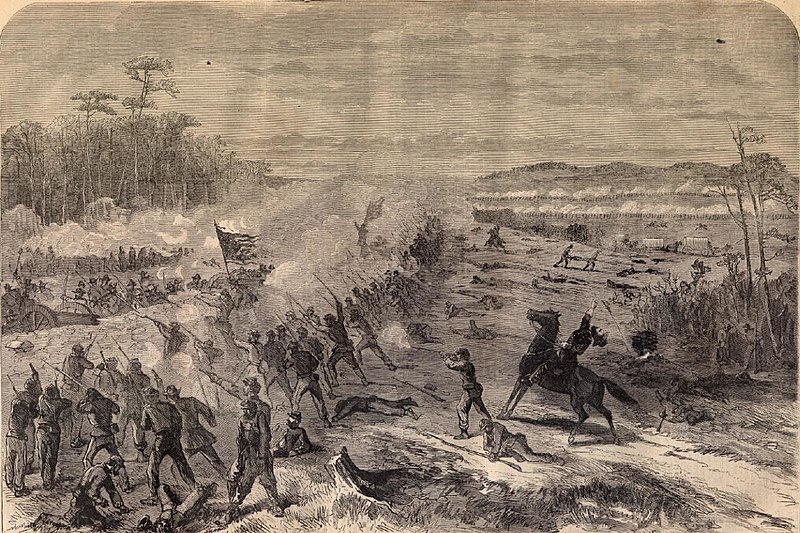

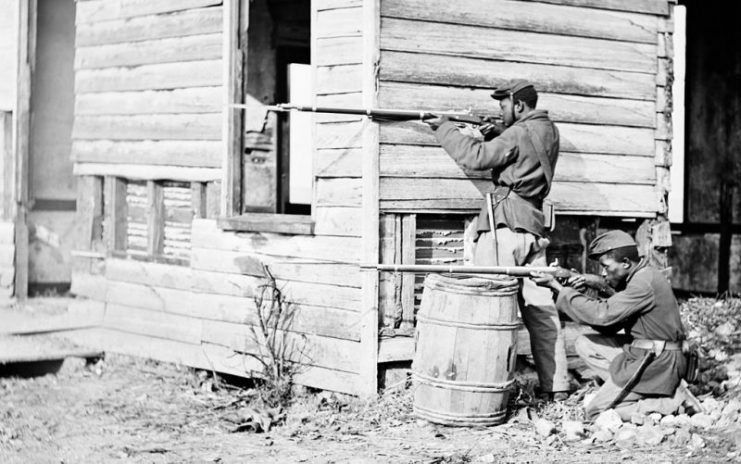

This is especially true of the history of the American Civil War, particularly the history of black soldiers that fought in the conflict. For example, Williamson County in Tennessee had more slaves than free Americans, and when the war started most of those slaves traded in their lives of slavery for that of a soldier.

It’s the kind of history that historians sometimes prefer to forget, but in Franklin on Memorial Day, hundreds of people gathered to honor and remember the sacrifices of those who gave their lives both for freedom and their country.

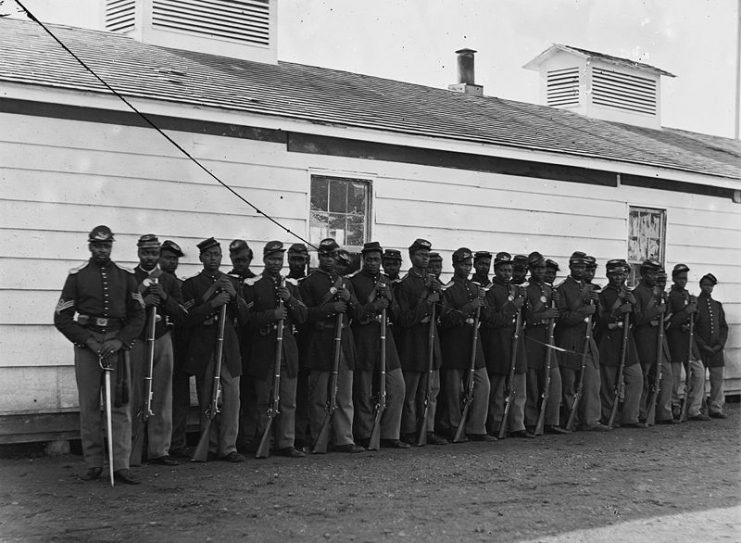

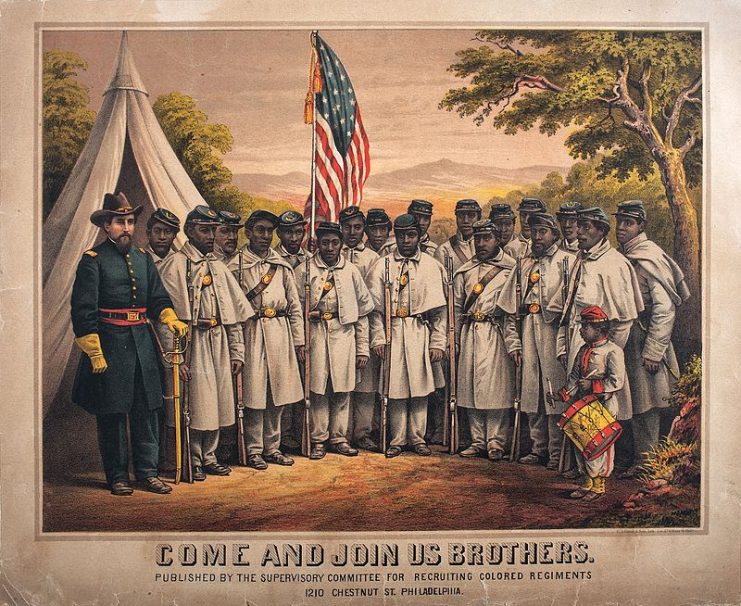

One of the lies told about Williamson County slave soldiers is that only eight men fought in the war. Five of these joined the Navy, while the other three were identified from the U.S. Army’s segregated division, called the “U.S. Colored Troops.”

Over the past twenty years, researchers have uncovered the truth through documents and stories that confirm over 300 slaves from Williamson County fought for the Union in the Civil War. According to Tina Jones, a researcher involved in this work, the number of Williamson County’s war dead was 59, which amounted to 20 percent of the total number of Williamson County soldiers.

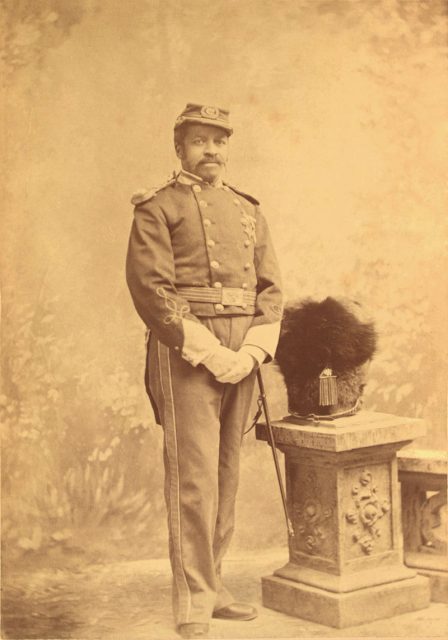

Descendants of the soldiers performed a re-enactment at the ceremony to bring home the sacrifices of their forebears. Shortly before the holiday weekend, Jones put the final touches on an exhibit in downtown Franklin inside the Williamson County archives while a crew installed newly engraved brick pavers outside the Williamson County Veterans’ Park. Altogether, Jones was able to identify twenty-nine individuals, each of whom was recognized.

The story began for Jones in 2006 when she was helping a group of African American seniors from her home church at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church run down through their personal genealogy. It helped spur an interest in the African American side of Williamson County’s history.

She learned that about 12,000 slaves had lived in the county before the Civil War. She sought out such diverse sources of information as genealogy sites, military pension records, and headstones from local cemeteries. It wasn’t long before she started discovering records pertaining to the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) that hailed from Williamson County that vastly contradicted the official record.

“So many great things are happening with African American history that are being brought out that haven’t been brought out before,” said Alma McLemore, Williamson County African American Heritage Society president.

“There are people working to tell the whole story.”

One such thread that has been brought to light is the story of the Battle sisters. It was through DNA testing that the sisters, Thelma and Emily Battle, learned they were related to Felix Battle, and promptly attended the ceremony to do him requisite honor. At thirteen, Felix Battle joined up with the Union troops as a musician and was present at the Battle of Nashville. He earned his freedom and continued on to become a pillar of his community.

Thelma Battle said that she was proud to be a descendant of Private Battle, and added that this group of men had long since been overdue for their honors. She sponsored a paver dedicated to him on the 28th of May. Seaman Stephen Bostick’s paver was dedicated the same day sponsored by his granddaughter, who lives in Ohio.

The Slaves to Soldiers Project includes a total of 27 brick pavers installed with the names of former slaves turned Civil War soldiers. The project’s fervent hope is to sponsor all of the pavers to honor the soldiers that history has since forgotten, especially since Memorial Day 2018 was the first year black service men’s names have been included.