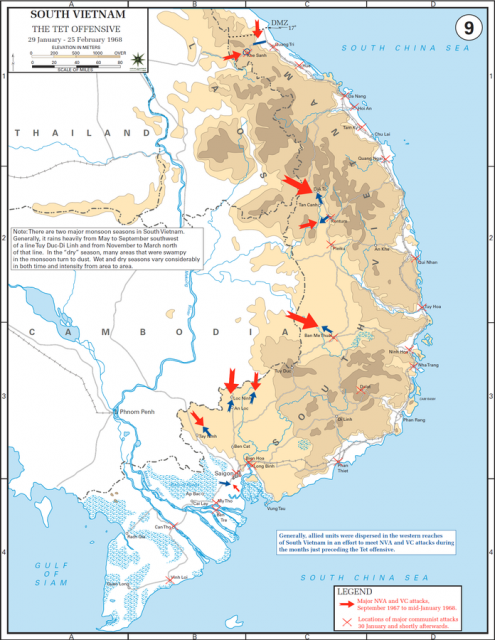

After the launch of the Tet Offensive campaign on January 30, 1968, in South Vietnam, a series of battles were fought between the southern Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and the Northern People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN).

The United States and other allied nations fought on the side of the South and the campaign was named after the Tet holiday which marks the Vietnamese New Year. One of the deadly confrontations involved with the Tet Offensive was the Siege of Hué.

Hué city was notably important due to its cultural and spiritual heritage as well as its proximity to the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone (DMZ); a dividing line separating North and South Vietnam.

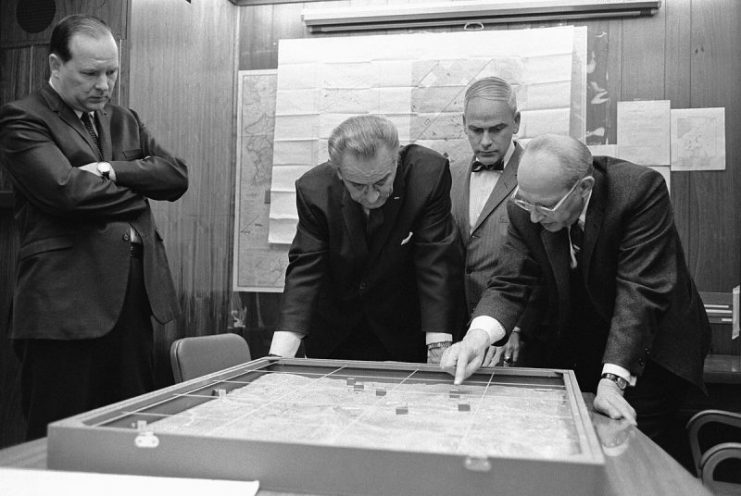

General William Westmoreland rightly predicted the enemy’s move to capture the city when he was asked to place himself in the enemy commander’s shoes by U.S. President Johnson in a meeting in February 1966.

Westmoreland described the city to be the symbol of a United Vietnam, a place of sentimental value to both parties of the war, one whose capture would undoubtedly have a strong psychological impact on both the North and South Vietnam.

His words were confirmed in the early hours of Jan 31, 1968, barely two years later when a Northern PAVN division and communist Viet Cong forces carried out an organized invasion of the city.

As was properly anticipated by the North Vietnamese, the city was not prepared for an attack, especially at that time of the year. Being the center for spiritual, cultural, and educational institutions, the city was greatly revered and was spared a lot of the horrors of the Vietnam War. This had caused the city to be largely lacking in military protection.

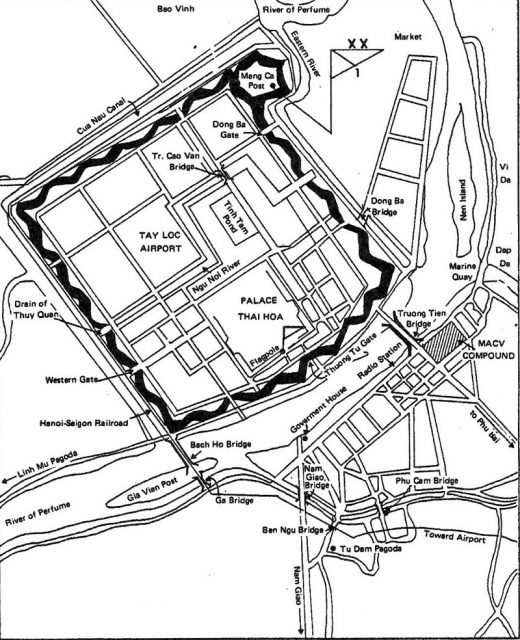

The only military support inside the city was from the ARVN 1st Infantry Division, whose headquarters was northeast of the citadel in the Imperial city. Some of these soldiers were still away on leave as a result of the Tet holidays. Other military support included the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), whose headquarters was positioned on the south side of the Perfume River.

Not detecting any signs of an offensive, Viet Cong Forces were allowed into the city under the ruse of coming to visit their family for the holidays, which they took advantage of, smuggling in weapons undetected under the pretext of bringing gifts of food and fruit. The communists had made a decision to strike and what better time than when the enemy isn’t watching?

A new light was introduced into the city’s night as the invaders’ flare hit the sky, signaling their comrades to begin the assault. With objectives to secure the ARVN headquarters on the northeast side of the citadel and other strategic military locations in the city, two battalions of the 6th Regiment of the PAVN were released into the calm and quiet of the city, heralding a vicious start to the Vietnamese New Year.

Mortars and a shock wave of rockets greeted the U.S. MACV around 3:40 AM and the battle began. Disguised as ARVN soldiers, a six-man PAVN sapper team breached the Chanh Tay gate, killing the guards and ushering in their assault team charged with carrying out the siege of the Mang Ca garrison. They had to change their plan when they found the entrance to the sewer which led into the fortress was blocked.

They found another way in but were locked on to by an ARVN-wielded machine gun; bullets were sprayed into the air, taking down twenty-four of the forty-man PAVN assault team in their attempt to capture the Mang Ca. As more PAVN poured in, they pressed the ARVN’s General Ngo Quang Truong and his men to the confines of their fort, gaining control of the citadel.

General Truong’s resistance was a two hundred man squad of staff and officers not ordinarily expected to be engaged in combat. However, they fought relentlessly to keep the PAVN at bay. The Hac Bao, aka “Black Panther” Reconnaissance Company, of the 1st division, composed of fifty soldiers, were called upon by Gen Truong to support the soldiers at the fort and prevent it from falling into enemy hands.

The Black Panther Company had been at the Hué Citadel Airfield, which was also under attack from the PAVN 800th Battalion of the 6th Regiment. The battle raged from the early hours until dawn, resulting in the destruction of all aircraft stationed there, including the two new Cessna 0-2 Skymasters that had just been delivered the previous day to replace the older Cessna 0-1 Bird Dogs.

The exit of the Black Panther Company from the airstrip resulted in success for the PAVN forces and they held control there until February 3 when it was reclaimed by ARVN 3rd Infantry Regiment and 7th Armoured Cavalry Squadron.

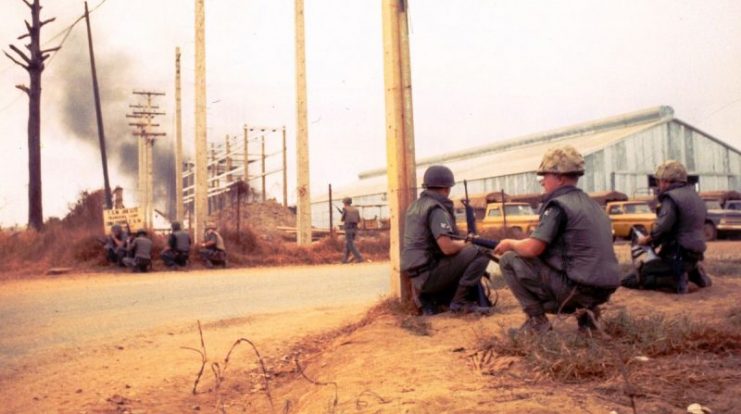

Meanwhile, American troops were constantly being assaulted by the PAVN 4th Regiment but were under less serious threat from them because they had a machine gunner who kept them busy from a guard tower and some troops who held them off from a bunker with individual weapons. They were able to keep the enemy from advancing until the defensive units in the station were able to organize themselves into a formidable resistance.

In the wake of events that morning, PAVN forces had captured the citadel and the Hué Citadel Airfield. General Truong had called in reinforcements of the 3rd Troop of his 3rd Regiment, the 7th ARVN Cavalry, and the 1st ARVN Airborne Taskforce. It was an “all hands on deck situation” and the Ma Cang garrison needed every available man they could get.

The 2nd and 7th ARVN Airborne Battalion, along with the 3rd Troop, entered into the citadel after a long standoff with PAVN 810th battalion forces in the early hours of the next morning and heavy losses were sustained on both sides, with casualties on the side of the ARVN numbering as high as one hundred and thirty.

Of the twelve armored trucks with which they departed, four had been destroyed. The South Vietnam forces claimed to have taken out two hundred and fifty of PAVN blocking forces stationed outside the citadel, taking some prisoners and securing their weapons.

The 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 3rd ARVN Regiment marched eastward along the northern bank of the Perfume River in a futile attempt to get into the citadel. They were repulsed by defending PAVN troops.

The 1st and the 4th Battalions, on the other hand, were also in a heated battle with enemy soldiers southeast of the citadel, they were soon surrounded and running out of ammunition. It was at this point that the commander of the 1st Battalion, Captain Phan Luong, ordered his unit to retreat to the Ba Long valley outpost leaving the 4th Battalion at the center of the action. With fewer enemy forces to deal with, American and ARVN units made their way to the citadel.

Two Viet Cong battalions had managed to seize the Thua Thien Province HQ, the police station, and other government buildings despite the efforts of Lieutenant Colonel Phan Hu Chi and the AVRN 7th Armoured Cavalry Squadron to break the enemy’s hold in that area.

By dawn, all areas south of the river excepting the Landing Craft Utility and the MACv had been overrun by communist army factions.

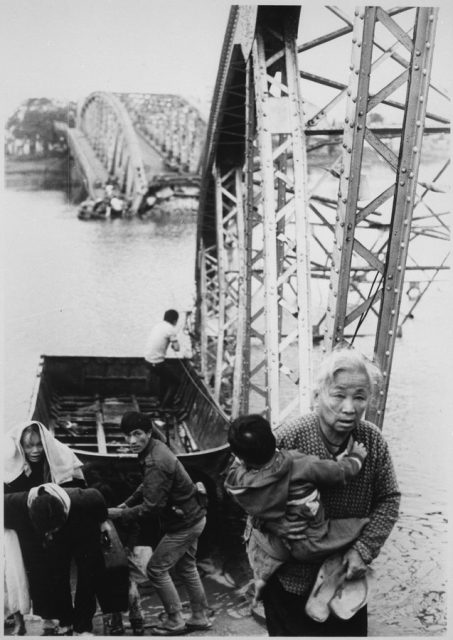

The gold-starred blue and red flag of the National Liberation Front (NLF) could be seen on the bloodstained streets of Hué City as well as the lifeless bodies of fallen soldiers in gutters and on the road. Instead of festivities, Hué’s Tet day had been replaced with mourning.

The Phu Bai Combat Base was not spared from the action as the airfield was attacked with mortar and rocket fire by the Viet Cong, the Combined Action Platoons (CAP), Popular and Regional Forces in the region.

The Marines were neck deep in Tet Offensive action. Brigadier General Foster C. LaHue, the Task Force X-Ray commander, dispatched Company A, a single rifle company 1st Battalion, 1st Marines (1/1), to provide support to the city and reinforcements to the MACV and the LCU. LaHue, like most others, had been given intelligence which underestimated the PANV presence in the city, prepared to swoop in and save the day, but the marines were in for a surprise regarding the size of the enemy’s army.

Company A marched north from Phu Bai along Highway 1, joining the four M48 tanks that were already on route. They proceeded to cross the Phu Cam Canal arriving close to the MACV building but became engaged in a standoff with the enemy. They were reinforced by Company G of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines (2/5), under Lieutenant Colonel Marcus J. Gravel, commander of the (1/1).

They forced their way into the MACV compound and assumed strategic positions around the building and the Navy’s boat deployer. They also secured the base of the Nguyen Hoang Bridge, a Highway 1 crossing point which leads from the river to the citadel.

With the American outpost reinforced, emphasis shifted to General Truong’s headquarters, the Ma Cang. LaHue was given directives to dispatch (1/1) and (2/5), Companies A and G marines respectively, to cross the river and reinforce the garrison.

Company G was the team deployed to the Nguyen Hoang Bridge. After taking the bridge, they abandoned it and fell back to the MACV compound after realizing that they wouldn’t be able to hold it.

Meanwhile, PAVN and Viet Cong soldiers continued to troop in, and despite attempts by MG John J. Tolson’s 1st Cavalry Division and 12th Cavalry Division to isolate the city, five communist battalions successfully rejoined their comrades and provided them with ammunition as well as manpower to hold their siege.

It had rained on 30 January and from February 2, the rain continued almost throughout the entirety of the battle, hampering the effectiveness of aerial support from the U.S. air force. However, Company F (2/5) landed reinforcements in the MACV compound on February 2.

The (2/5) in conjunction with some ARVN troops under the command of Colonel Stanley S. Hughes began clearing out the city building by building in an attempt to flush out enemy forces. The streets were under direct assault from snipers and the marines, who were used to jungle warfare, had to improvise and employ new tactics to counter the enemy’s tactics.

The Marines’ use of M-48 tanks was an added advantage as well as the 106 recoilless firearms they used to create routes through the buildings. However, the casualty rate of the American support was still very much on the high side.

The Marines swept through the city and cleared the city hospital, treasury, Provincial Capital, university, and the Joan of Arc School on 6 February amidst massive PANV-NLF resistance, and by 10 February, Colonel Hughes had successfully secured the south side of the city.

Ten days of fighting saw advances from the 1st Battalion 5th Marines under Major Robert Thompson emerging from the south side. Also, the combined efforts of ARVN and 3rd Battalion 5th Marines (3/5), and the 1st Cavalry Division, who wreaked havoc on the PANV supply installation at La Chu Woods to the west of the city,

Finally, the 6th Regiment gave up their siege of the citadel and fell further back into the city which was then ravaged by the marines as they secured their position in the Imperial Palace, both events taking place on 23 February.

With the enemy troops scattered all over, some still hiding in buildings and others lurking in the bushes, ARVN and U.S. Marines conducted a final sweep of the city, eliminating all traces of PANV and Viet Cong forces on 26 February, and by midnight, 27 February, mop up operations were concluded, ending the twenty-six-day nightmare of Hue City.