Several weeks after graduating from Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri, in late spring 1966, the late Roger Buchta was drafted into the U.S. Army and sent to Texas for both his basic combat training and to become a combat medic.

Although the military delayed his aspirations of becoming a teacher, the young soldier never complained about the circumstances that befell him even when preparing to deploy to Vietnam.

Arriving at a military base located near Qui Nhon—a coastal city in central Vietnam—during the second week of October 1967, Buchta wrote home to his family in Lohman, Missouri, the following month describing his assignment to a U.S. Army ambulance company that supported a military hospital.

“Our duties consist mostly of transporting patients and supplies…. We are also on ambulance commitments at the pier and at the air field in case of a crash. So, between calls, if there are any, we sleep,” penned Buchta on November 1, 1967.

Nine days later he wrote, “Qui Nhon is mostly a supply area. Through its port come the supplies that are used by units in the northern part of Vietnam.

There is also a large airport here. About twenty miles south of Qui Nhon they are building an airstrip that can and will be used for commercial airlines on which the military heavily depends for transporting troops from the states.”

The soldier received a promotion to private first class shortly after arriving overseas and, as the weeks passed, word began to filter down from higher headquarters that their field hospital would soon be packing up and moving to another location, potentially to a camp near Saigon.

The 542nd Medical Company, to which the medic was attached, transferred to Cu Chi, Vietnam, in early December 1967.

Home to the 25th Infantry Division, Maj.Gen. Fred C. Weyand, who served as the division’s commander, noted Cu Chi had long been a sanctuary for the Viet Cong,” requiring “several weeks of fierce fighting” to secure the base camp prior to Buchta’s arrival.

“It’s a calm Wednesday night here in Cu Chi,” wrote Buchta on December 13, 1967. “We have taken over a large dispensary and a small hospital. The dispensary receives casualties directly from the field. There is a huge helicopter field across the road from the dispensary and hospital. Most of the casualties come in by ‘copter.”

He also described a network of concealed bunkers in the vicinity of Cu Chi that became something of legend. This vast network of tunnels, spanning an impressive 125 miles in total length, were accessed by hidden entrances in the forests surrounding Cu Chi and allowed enemy troops to move about the area virtually undetected.

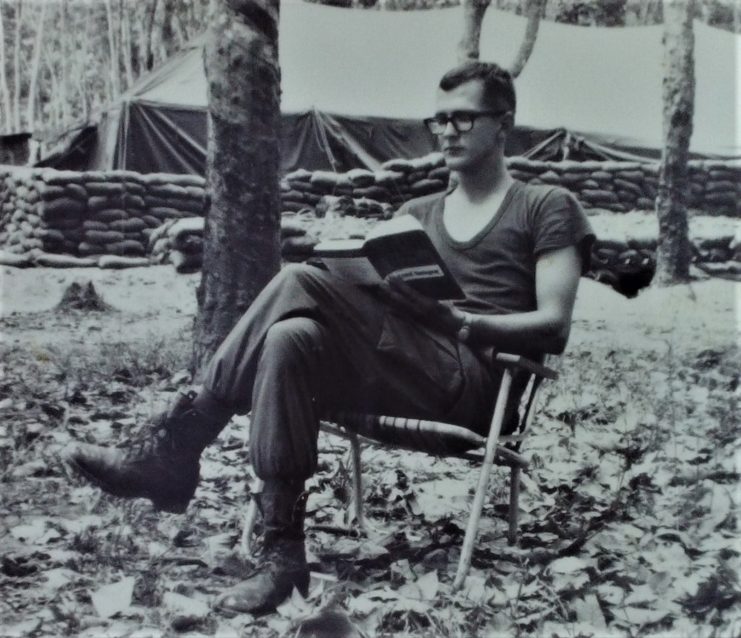

The holidays came and went, during which Buchta assisted with the emergency delivery of Vietnamese twins on Christmas Eve, whom he had the honor of naming Mary and Margaret. Christmas miracles notwithstanding, one of the most interesting events came the following month after his unit moved to Lai Khe, a military base located on a rubber plantation near Saigon.

It was here that he witnessed one of the most intense moments of the war—the Tet Offensive. Shortly after his arrival at Lai Khe and his subsequent attachment to the 18th Surgical Hospital, Buchta informed his family in a letter dated January 13, 1968, that an element of danger had developed.

“The first part of the week there was quite a bit of activity in the area,” he wrote. “One night about 3:00 a.m. the VC (Viet Cong) lobbed a few mortars on one side of the camp.

Then they tried a ground attack. It was a futile effort. There was no one hurt during the mortar barrage and very few during the ground attack.”

Several days later, he wrote of his work duties, “In a surgical hospital, you deal with casualties directly from the field aid stations who require emergency surgery. After recovering from the operation, the casualties are evacuated to larger hospitals. Some of the more serious are sent to Japan and back to the states.”

Enemy activity and casualty levels dissipated for a few days, a moment that could be considered the calm before the storm.

When the opening stages of the Tet Offensive began to evolve on January 30 and 31, 1968, enemy forces nearly overwhelmed several U.S. bases, creating great cause for concern even for those in a non-infantry capacity.

“He informed me that Viet Cong attempted to breach the perimeter of the base at Lai Khe and the medical staff were ordered into a ditch that essentially surrounded the base,” said the former soldier’s older brother, Don Buchta.

He continued, “They had their M-16 rifles and all hell was breaking loose around them with a firefight going on and mortars exploding, when one of the sergeants hollered, ‘Ok, men! Lock and load!’”

With a pause to recollect conversations from years past, his brother added, “Roger said it was one command that he would always remember. When all the firing finally ended, he remembered that there were about thirty Viet Cong that had been killed but the U.S. didn’t suffer any casualties.”

Reports indicate that when the Tet Offensive ended, the base camp at Lai Khe endured more than 980 rocket and mortar rounds. Fortunately for medics, the camp had been well protected by the gallant soldiers of the First Infantry Division.

As the words written by Buchta to his family a couple of days later reveal, he realized the significance of the event he had recently survived and his bewilderment with the resolve of the enemy.

Another Article From Us: The most decorated Marine in United States history – Chesty Puller, American Hero

“As you undoubtedly heard in the news, the VC and NVA (North Vietnamese Army) have been kicking up their heels a bit. They have a strange way of celebrating their new year. I can’t understand sometimes how these people can absorb the tremendous losses that they suffer and still continue fighting.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.