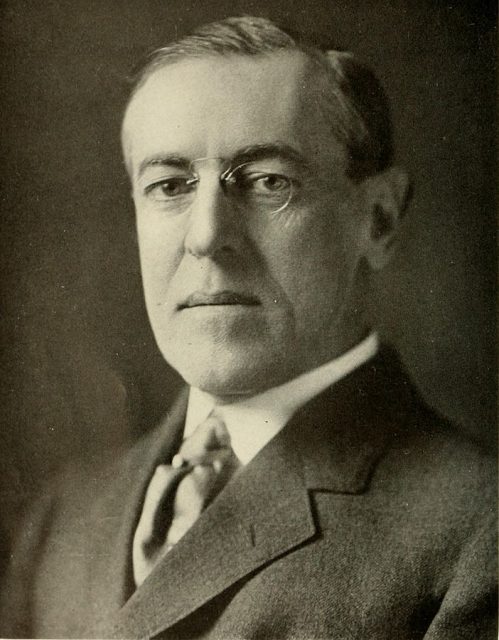

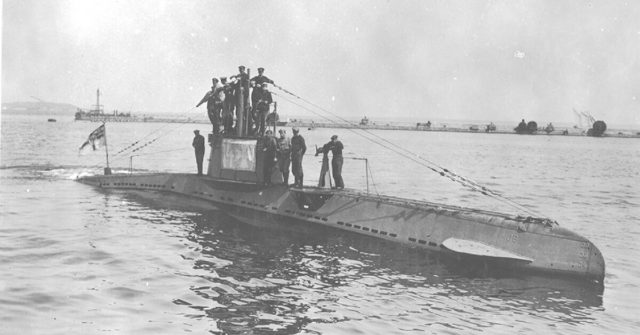

When Woodrow Wilson put forth his proposal to arm American merchant vessels in February of 1917 his reasoning was simple and straightforward: the threat of German U-Boats following Germany’s declaration of unrestricted naval warfare was a threat to American citizens.

Wilson was faced with either withdrawing American merchant ships from their transatlantic trade routes to spare the lives of American mariners or engaging the German U-Boats as they appeared – but he could not unilaterally declare war on Germany, nor was he interested in doing so.

Opponents of his bill to arm civilians reacted as though he did intend to take America to war, however, and sought to cast his maneuvering as anti-democratic warmongering that sought to subvert the division of powers in the American government to provoke the Germans to such a degree that America would have no choice but to declare war.

The chief opponents to Wilson’s bill were a group of anti-war Republicans who believed that trade with the British was unnecessary and not worth preserving at the risk of angering German U-Boats. The de facto leader of this group, Wisconsin Senator “Fighting Bob” La Follette, arranged a filibuster to stall the bill with only three days remaining in the 64th Congress.

The chair refused to recognize La Follette’s right to speak, but his cohort nevertheless spoke at length and stalled consideration of the bill for long enough to allow the bill to expire without passing it. The speech La Follette had prepared was later submitted to the Congressional Record. It contained many points that would have prolonged the debate had he been allowed to proceed.

According to La Follette, the chief benefactors of Wilson’s bill would include the British owners of the American Line, a shipping company lobbying for its passage. La Follette’s arguments were complex and convoluted, but all returned to a locus of foreign influence over American government affairs and undue exercise of authority by the President of the Republic.

He further argued that Congress was not being given sufficient time to debate the consequences of the bill – a situation he deliberately aggravated with his filibuster.

Though he referred to Britain’s situation as a “bottomless pit of [European] horror,” he argued against American involvement on the grounds that Germany had not yet attacked America despite Germany’s openly expressed intention to do so with the resumption of unrestricted naval warfare.

Immediately after the expiry of the sitting Congress, the incoming Senate announced their plans to enact a rule called cloture: if a Congressional debate was deemed to be going on for too long without significant progress, a majority of Congress could vote to end debate and push the issue to a vote without further discussion.

This prevented a minority in the House from effectively hijacking the proceedings to achieve their goals or forestall bills they disagreed with, and this legislation was received as the restoration of democratic institutions after a critical abuse of legislative protocol.

For his part, La Follette was pilloried in the court of public opinion; his comments downplaying American’s grievances with Germany were received with disgust throughout the country. He was very nearly expelled from the Senate in addition to becoming the target of national condemnation, the nexus of which was his alma mater.

Follette was burned in effigy on the University of Wisconsin campus, and his ostracization continued when he opposed the American declaration of war against Germany only months after the filibuster. Though he was remembered as “the voice of humanism in politics” by supporters upon his death, La Follette’s career would never recover from the actions that lead to the passage of cloture legislation.