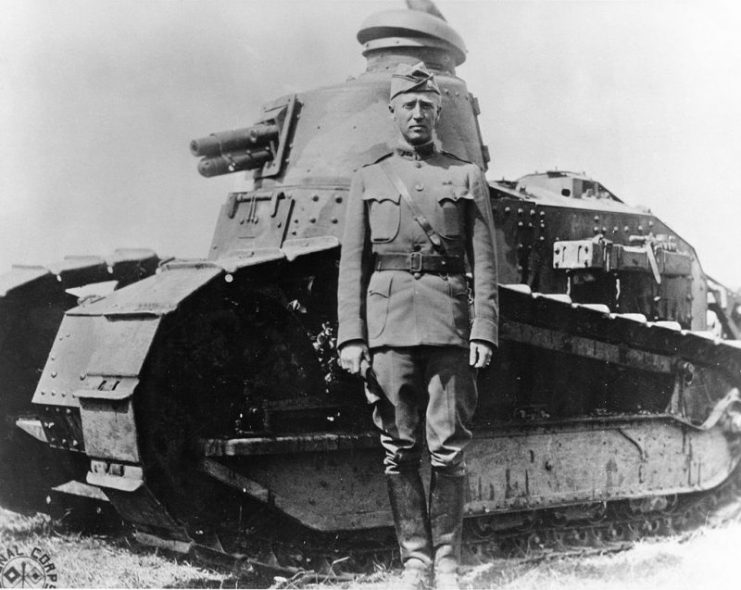

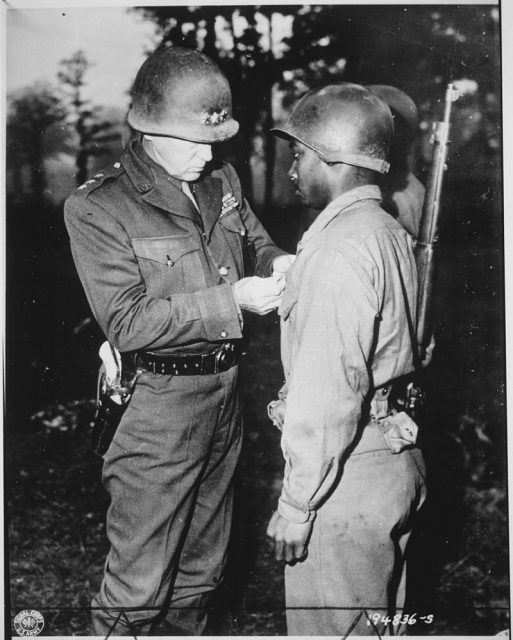

General George S. Patton was one of the most controversial and flamboyant American military leaders of World War II. He commanded the U.S. 7th Army in North Africa and Sicily and the U.S. 3rd Army in France and Germany.

He died following a road accident in Germany in December 1945, but since the 1970s there have been persistent rumors that he was actually assassinated.

When the war in Europe ended on May 8, 1945, Patton hoped for a transfer to the Pacific Theater of Operations, where fighting against the Japanese continued. However, the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought that war to an end just three months later.

While most of the world celebrated the end of WWII, Patton was despondent. He wrote in his personal diary on hearing the news of the Japanese surrender, “Yet another war has come to an end, and with it my usefulness to the world.”

Patton was appointed Military Governor of Bavaria in July 1945, but his tenure in that position was short. He retained ex-Nazis in positions of authority in Bavaria, justifying this by noting that it was unavoidable because most people with civil service experience had been forced to join the party. When a reporter for a U.S. newspaper challenged this, Patton responded by comparing Nazis to Republicans and Democrats in America.

Patton’s seeming admiration for Germans, referring to them as “the best race in Europe”; and his evident anti-Semitism, when he accused the U.S Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau Jr. of taking “Semitic revenge against Germany,” did not go down well with the majority of Americans in the immediate aftermath of the war.

Patton was also an outspoken critic of the Soviet Union, which at that time was still America’s ally. At one point he said: “We’ve kicked the hell out of one bastard, only to help establish a second one…more evil and more dedicated than the first.” Patton favored continuing WWII, but with America and the Allies taking on the USSR.

His statements caused outrage in America and on September 28, Patton was removed as Military Governor of Bavaria. On October 7 he was also relieved of command of the U.S. 3rd Army. Patton was then appointed commander of the U.S. 15th Army, based in a hotel in Bad Nauheim in Hesse, Germany.

The 15th Army had no troops and consisted of only a small headquarters unit which had been given the task of compiling a history of U.S. involvement in WWII. Patton loved history and was initially enthusiastic about this new assignment, but he soon lost interest and became depressed.

He celebrated his sixtieth birthday in November and was due to begin leave on December 12. He seemed to be considering retiring from the Army, in which he had served since 1909.

On the morning of Sunday December 9, 1945, Patton decided to go pheasant hunting near the town of Mannheim with his friend and Chief of Staff, Major General Hobart R. Gay. Patton and Gay set out in Patton’s staff car, a 1938 Model 75 Cadillac. They were driven by Patton’s regular chauffeur, PFC Horace “Woody” Woodring.

They set off early from 15th Army HQ in Bad Nauheim. Another man, Technical Sergeant Joseph Scruce, set off separately in a jeep which contained their guns and a hunting dog. They had arranged to meet later in the morning at a U.S. military police checkpoint.

Patton and Gay visited Roman ruins at Saalburg before continuing on the autobahn towards Mannheim. They stopped at a military police checkpoint at Viernheim, on the outskirts of Mannheim, where they rendezvoused with Sergeant Scruce.

The two vehicles set off towards Mannheim in convoy, with Scruce in the lead. Patton was sitting on the right side of the rear seat of the staff car and Gay was beside him.

They arrived at a railroad crossing just as a train was approaching. Scruce managed to get over the crossing before the train arrived, but Patton’s car was forced to wait until it had passed. After the train had gone, Woodring set off after Scruce, who was by now out of sight.

It was around 11:45 AM and there was almost no other traffic on the road on that bitterly cold Sunday morning, but as Woodring began to slowly accelerate on the icy road, he noticed two U.S. Army trucks parked on the shoulder of the opposite side of the road, facing towards them.

As they approached, one of the trucks started to move forward, driven by T-5 Robert L. Thompson. As Patton’s car was about to pass, the truck suddenly veered across the road in front of them, turning left towards the entrance to a temporary U.S. Quartermaster’s storage area without giving any form of signal.

There was no chance to avoid a crash and the right front of the staff car hit the right front of the truck. The impact wasn’t severe – the speed of the car was estimated to have been under twenty miles per hour and the truck was traveling at no more than ten miles per hour. The only damage was to the right front fender of the staff car.

The truck driver, his two passengers, and Woodring and Gay were completely unhurt, but it was immediately obvious that Patton was seriously injured.

Woodring and Gay had been looking forward and both were able to brace themselves in the instant before the impact. Patton had been looking to the side and he had been thrown forward, striking his head on the partition between the front and rear seats.

He was bleeding from a wound to his forehead and he seemed unable to move, though he was conscious. A U.S. Army ambulance and medics arrived and attended to Patton in the Cadillac before taking him to the 130th Station Hospital of the U.S. 7th Army in Heidelberg, about fifteen miles away.

Patton arrived at the hospital at 12:45 PM. He was found to have severe dislocation of the vertebrae in his neck which had caused spinal cord damage. He was paralyzed from the neck down.

Doctors from Great Britain and the U.S. were flown in, but there was little that could be done. However, by December 19, plans were being made to fly him back to the U.S. for specialist treatment.

On December 21, Patton’s wife Beatrice read to him in the afternoon and then took a short break to have a meal. While she was eating, a hospital orderly appeared to tell her that her husband was dead.

The official cause of death was given as pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure. Patton was buried in the U.S. Military Cemetery at Hamm in Luxembourg, next to U.S. 3rd Army soldiers who had died during the Battle of the Bulge.

For thirty years, no one seemed to doubt that Patton’s death was anything but a tragic accident. Then, in 1974, the novel The Oshawa Project was published (The Algonquin Project in the U.S.) by British thriller writer Frederick W. Nolan.

The novel featured a plot by President Truman and General Eisenhower to assassinate a troublesome American general in the period just after the end of WWII.

General Campion, the assassinated general in the novel, is clearly based on Patton, being a legendary war hero who is also the Military Governor of Bavaria and an outspoken critic of the Soviet Union.

Although Nolan never claimed that this was anything but a work of fiction, people began discussing the possibility that the death of George Patton was not a simple accident.

In 1981 a new biography of Patton was published, The Last Days of Patton, by Ladislas Farago. This hinted that Patton’s death might actually have been the result of a plot, though it didn’t produce any new evidence.

It wasn’t until 1993 that the first non-fiction book solely on this topic appeared: Death – The Murder of General Patton, privately published by Stephen J. Skubik. Skubik, a former Army Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) agent who had also worked as an Eastern Europe advisor to a number of U.S. presidents.

He claimed that he had become aware in 1945 of a plot by the Russian People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) to assassinate Patton. But, he said in the book, when he told his boss, he was shipped back to the U.S.

In 2008 another much more detailed book about the death of Patton appeared: Target: Patton: The Plot to Assassinate General George S. Patton by journalist Robert Wilcox.

This contained even more explosive material. Wilcox had interviewed Douglas DeWitt Bazata, a former member of the Jedburghs, a team of American, British and French saboteurs and assassins who had operated in occupied France in the period before the Normandy landings.

Bazata died in 1999, but Wilcox said that Bazata had given him an interview shortly before his death, in which he told how he had been ordered by William Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the CIA, to assassinate General Patton.

Wilcox claimed that Bazata said the accident involving Patton’s car had been set up, and that in the immediate aftermath of the impact Bazata had shot Patton using a weapon which fired a form of rubber bullet, designed to kill without penetrating the body or leaving a recognizable bullet wound.

Wilcox also claimed that Bazata said that when this attempt to kill Patton was unsuccessful, the OSS colluded with the NKVD to allow that organization to poison Patton in the hospital at Heidelberg.

Wilcox undertook extensive research and claimed that several U.S. military records relating to the death of Patton had vanished, most notably a report submitted by a U.S. military policeman, Lieutenant Peter Balabas, who claimed to have been one of the first people to arrive on the scene.

Balabas, who later became a senator for Virginia, said that he had prepared a report on the accident in which he noted that Patton’s injury was surprising given the very low speed of the impact. However, no one has been able to find this report.

Wilcox also examined the 1938 Cadillac in which Patton died, which is on display at the General George Patton Museum of Leadership at Fort Knox in Kentucky. Wilcox discovered that parts of this vehicle are actually from a 1939 Cadillac which, he claimed, confirmed that there had been a cover-up.

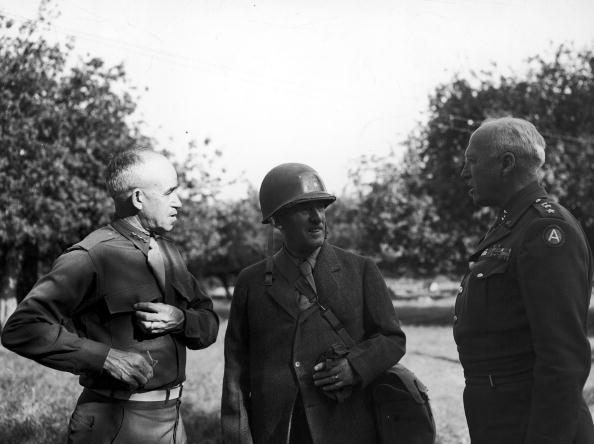

After the publication of Target: Patton, Wilcox was approached by a third witness, Bert C. Roosen, a German who was working as an interpreter for General Eisenhower in the immediate post-war period.

Roosen, who emigrated to Canada after the war and became a successful businessman there, was working on Eisenhower’s personal train where he claimed there had been an acrimonious argument between Eisenhower and Patton on a station platform outside one day.

Shortly after, Roosen had overheard a conversation among Eisenhower, General Omar Bradley, and Eisenhower’s aide General Bedell Smith. Roosen claimed that he heard Eisenhower angrily say “We’ve got to stop him.”

One of the others answered, “How? We can’t shoot him.”

The third said ominously, “Don’t worry. I’ll take care of it.”

In 2014, yet another book about the death of Patton appeared. Killing Patton: The Strange Death of World War II’s Most Audacious General, by Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard, repeated much of the detail from Target: Patton and concluded that the general was assassinated as the result of a plot.

In the space of thirty-five years, between the publication of The Algonquin Project in 1974 and Target: Patton in 2008, the possibility that General Patton had been assassinated moved from being the plot of a work of fiction to being regarded by some people as historical fact. But, can this really be true? In Part 2, we will analyze the various conspiracy theories to see whether any really look plausible.