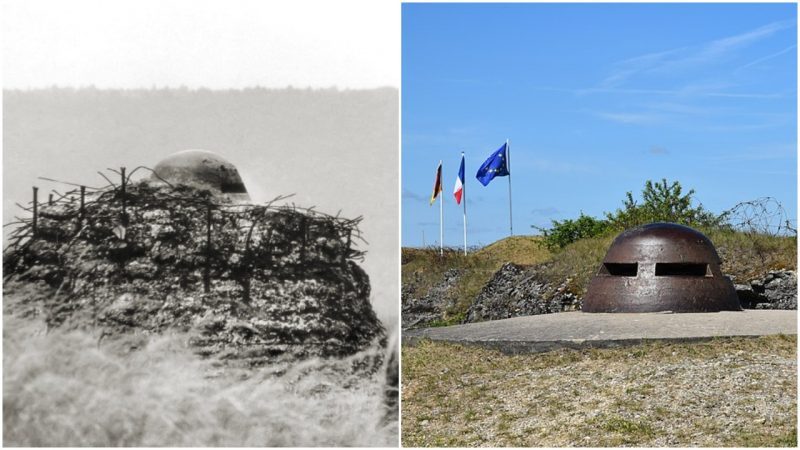

There is a hidden side to war that historians have only been able to see just recently due to our enhanced ability to both record and appreciate it. It’s the long-term after-effects left by the largest wars in human history, from the pockmarked walls leftover to commemorate the doomed resistance in Warsaw during the Second World War to the now placid bunkers of Vimy Ridge, built over 100 years ago during the Great War. Only now, many years later, do we really get to see how the healing process has come full circle.

The green grasslands of Beaumont Hamel in France ripple in the wind, only broken up by the ragged tears that were once the trenches where so many men fought and died. The poppy fields and graves overrun by nature are a mute reminder of the horror of those times.

Generations of fauna have grazed here, unaware and uncaring of the place’s bloody history. It’s a cliche to suggest that time heals all wounds, but for the places where soldiers fought the war to end all wars, the effects of time are visible.

At Spincourt forest in France, where the German army had constructed a hospital, rail connections and command posts, the bunkers still stand, albeit transformed by a blanket of green moss. The scene is the same in Ploegsteert Wood, Belgium, where moss covers the center of a bunker. The scene is peaceful and calm now. The years pass and the forest slowly but surely reclaims the site of some of the most vicious fighting of the First World War.

Entire communities were lost to history in the Great War, leaving only street signs and the occasional ruin to mark where life once flourished. But life finds a way. Now street signs like the one denoting the once Grande Rue, the former main street sign of Bezonvaux, France, which was literally obliterated in the Battle of Verdun, sit in a field of green, pointing now only to the horrors of the past.

Not even the shadow of once unimaginable destruction can go untouched for long by the resurgence of life. The unnatural land formations left behind, rent from the land by severe artillery bombardments during the Battle of Les Eparges, near Verdun, now covered with a lush green, new trees reaching up through the cracked and broken terrain towards the sky.

Even sites of great strife, where the greatest of human endeavors met with the horrors of so many abject calamities, such as the ‘Trench of Death’ in Diksmuide, Belgium, near Passchendaele, can provide glimmers of hope in the fullness of time. Now poppies grow, reaching up from the blood-soaked earth to present a scene of pastoral beauty in a place that witnessed so much suffering.

But the past also carries with it a warning. The future is dotted with the leftover dangers of the past. In Spincourt it is estimated that France and Germany fired 65 million artillery shells at each other during the war.

Millions never exploded and now await the unwary. They stand as a reminder of the consequences of humanity’s hubris, as ideological and technological advancements extend far beyond humanity’s maturity to control them they are likely, ultimately, to lead to greater bloodshed.

There’s a profound lesson to be found in these photographs. It’s a lesson that the individual, with their relatively short lifespan, isn’t usually capable of grasping, except in hindsight and aided by historians. It’s that regardless of the present tensions, both geopolitical and quotidian, humanity can rest assured that life will go on without it.

Some might suggest that this idea leans a little too casually towards nihilism, and others that it diminishes the human experience, but if considered from the right direction there’s a certain comfort in the knowledge that our mistakes will be ultimately forgiven.

But we should never forget, and that no matter what today’s challenges may be, we can take solace in the knowledge that these, too, shall pass.