Though most of us have never given such an unremarkable, humdrum object a second thought, the humble stirrup, used by horse riders for much of recorded history, has had an immense influence on the evolution of global geopolitics as we know them.

It may seem strange to refer to a simple loop of leather or steel dangling from a rider’s saddle as a piece of “technology,” but it was exactly that, and in the early days of its usage it was quite revolutionary.

Just as the phalanx formation upended the conventional wisdom of infantry combat when it was introduced in antiquity, adding stirrups to a rider’s saddle enabled the newly-united Mongol nation to emerge from relative obscurity in Northeast Asia into a terrifying fighting force that ruled the largest land empire in history for several generations.

Archaeological records indicate that the Mongols were using stirrups as early as the 10th century, and even at this early stage, they were being ornately but solidly crafted out of metal. Mongol horsemen were extremely skilled fighters on horseback, and they adapted their tactics to their enemies to great effect.

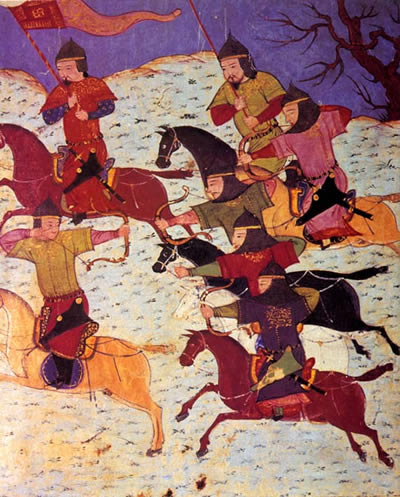

While history is filled with tales of armies winning by plunging forward until one side beat a retreat and was destroyed by pursuing opponents, the Mongols threw conventional warfare to the wind and practiced retreating as an offensive maneuver. Riding with stirrups gave the forces of Genghis Khan and his descendants a previously unimaginable tactical advantage.

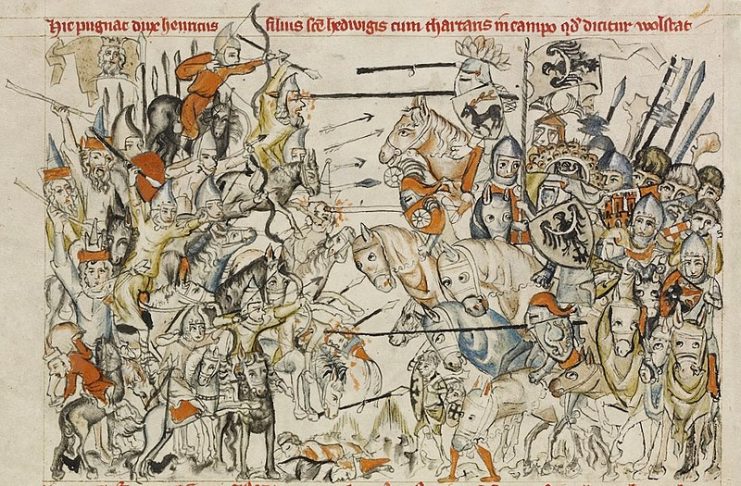

The Khans’ Eastern European foes were utterly unprepared to meet a force that could continue to attack while retreating. With the stability that two feet planted in stirrups gave them, the Mongol forces perfected the art of using their bows on horseback, doing so even while riding mounted backwards.

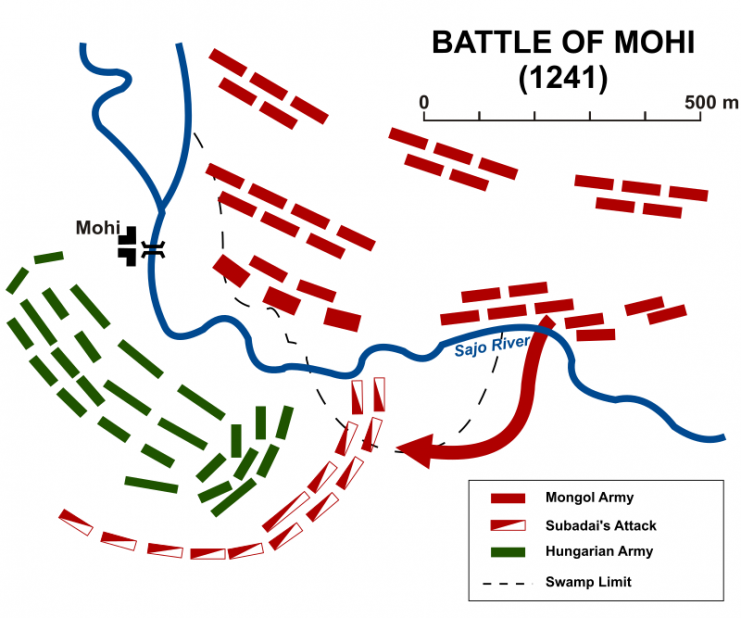

This allowed them to stay out of the range of the ground troops that would pursue them on their retreat, and they quickly learned that even a false retreat would lure Hungarian, Polish or Russian infantry and cavalry out of formation and into an ill-fated pursuit.

Marco Polo himself witnessed the Mongols in combat, writing that the horsemen “never let themselves get into a regular melee, but keep perpetually riding around and shooting into the enemy.”

Used in conjunction with stationary archers and mounted cavalry, the Mongols’ tactics brought them from their homeland to a distance uncomfortably close to Vienna over a period of decades. The trail that they blazed through Europe on the way to their ultimate prize was the result of their innovative use of a very simple device.

Had it not been for a series of events that caused them to return and wage war against the Song dynasty in China, they could have effected incredible changes on Western European society. Even without sacking Rome, the mark that they left on every culture they encountered is indelible – few conquering forces can claim to be the subject of contemporary historians as far apart as Rome and China.

The Great Wall of China is a testament to the organization that was required to rebuff their attacks. A Song general wrote about their use of the stirrup, describing its function in redistributing the weight of the rider – evidently, the stirrup was novel enough at that time to warrant mention and effective enough to warrant extensive additions to the Great Wall shortly after the Mongol forces’ return to the East.

If historians were impressed with the technology of the stirrup a millennium ago, they might be equally impressed at how little mind the world would give such a simple invention later in human history – like the phalanx, Europe and Asia adjusted to the tactics associated with the stirrup, and today it is a mere curiosity for those who no longer ride horses.