In 1942, the tumultuous tides of the Second World War turned against Singapore as Imperial Japan rolled over its minimal forces, taking approximately 25,000 prisoners. The prospects didn’t look good for the Philippines who were up next.

The Japanese launched a thorough and powerful attack, causing President Roosevelt to order General Douglas MacArthur to evacuate the field. On his way to Australia, MacArthur, on March 11, 1942, promised to return.

Japan took the Philippines, and during the evacuation committed one of history’s greatest war crimes, killing 10,000 Filipino and American prisoners during the Bataan Death March.

On June 4, 1942, American code-breakers learned of Imperial Japan’s strategy. Their plan began with the taking of Midway Island and would lead to the capture of Hawaii, expanding out from there to the rest of the Pacific.

Outnumbered and outgunned, the U.S. Pacific Fleet attempted but failed to ambush the Imperial Japanese armada. Japanese aerial scouts located the American fleet, but due to various communication mishaps, failed to relay the information back to their commanders.

For some reason, though, the Imperial Japanese fleet changed course, and the American bombers that were out searching for them never found their target. They searched determinedly, so much so that many American fighters on escort duty ran out of fuel, forcing them to leave their planes in the ocean.

Lieutenant-Commander John Waldron led a torpedo bomber squadron from the U.S. Carrier Hornet to do battle with Japanese carriers. He’d hoped to encounter a tactical situation that was both favorable and sufficient, but indicated to his men prior to the mission that if this weren’t possible, then he wanted for his men to do their best to inflict as much damage on the enemy as they could. They would only have one pass through, and he wanted each of his men to score a hit.

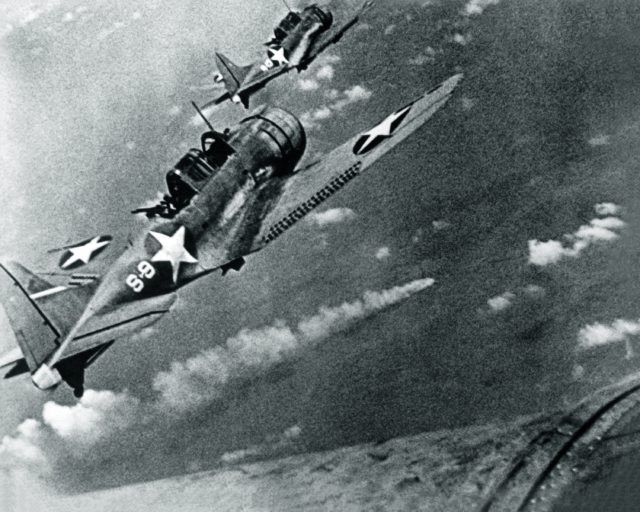

Waldron’s squad spotted the Imperial Japanese fleet first, and coming in at a low enough altitude to launch an attack, they flew into an intense defensive barrage. Thirty men had taken off that day – only one returned. For his leadership in battle, John Waldron received a posthumous Navy Cross.

An hour later, bombers from the U.S carriers Enterprise and Yorktown arrived, flying at a much higher altitude. Running low on fuel, they spotted the wake of the Japanese destroyers and followed onward to find the Japanese aircraft carriers: Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu.

As luck would have it, the Japanese “Zeros” were in the process of being refueled and rearmed following the fight with Waldron’s squadron. Five minutes later, the Imperial Japanese carriers were sent to the bottom of the Pacific, and Imperial Japan’s naval forces were cut in half, forcing them onto the defensive.

Chicago’s Midway Airport was named after this pivotal battle, and Chicago’s O’Hare Airport was named in honor of the war hero Lieutenant Commander Edward “Butch” O’Hare, who made his name in the Pacific theater.

General Douglas MacArthur made good on his promise to return, doing so on October 20, 1944. He brought his forces back onto Philippine soil full of renewed fervor for the destruction of his enemies and the enemies of his people, enraged by the barbaric ill-treatment that prisoners of war and the people of the Philippines had experienced at the hands of the Imperial Japanese forces.

On the day of MacArthur’s return to the Philippines, President Roosevelt sent a message to Philippine President Osmena.

“On this occasion of the return of General MacArthur to Philippine soil with our airmen, our soldiers, and our sailors, we renew our pledge. We and our Philippine brothers in arms, with the help of Almighty God, will drive out the invader; we will destroy his power to wage war again, and we will restore a world of dignity and freedom.”