Unable to stop the German advance in Europe, British soldiers fled through the Port of Dunkirk with French help. Weeks later, the British thanked their allies by killing over a thousand of them.

At the start of WWII, Britain had the biggest navy in the world, while France had the second largest. Both were, therefore, confident of a quick victory against Germany until the latter invaded Belgium, the Netherlands, and Northern France on May 10, 1940 – hence the evacuations at Dunkirk.

On the same day, Winston Churchill became Britain’s Prime Minister. Britain’s fleet was scattered throughout the world, and its supply ships were being sunk by German U-boats. The French fleet was in danger o falling to the Germans.

Churchill reminded the French of their treaty – that neither could surrender without the other’s agreement. Germany had Northern France and Ports that put them within 20 miles of the British coastline.

Desperate, Churchill asked President Franklin D. Roosevelt to send over 50 American warships. Roosevelt was sympathetic, but the US elections were coming up. His campaign vow? To never again involve the country in yet another European war.

When the Germans reached the English Channel on May 20, Churchill again asked Roosevelt for help – this time with a twist. If Britain fell, Hitler might want its fleet as part of an armistice deal. With the French and British Navies under German control… well, America is just across the Atlantic (hint-hint!).

Big mistake. Roosevelt understood the message to mean that Britain was going to surrender. He called Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King and made him an offer – forget Britain and keep your fleet in Canada. We will defend North America together.

As Canada was part of the British Empire, King was shocked. He told Churchill, of course, beginning the countdown to disaster.

The Germans took Paris on June 14. Four days later, France officially surrendered. On June 22, the new French government recognized the joint German-Italian occupation and were allowed to keep the southern half of France. On one condition – they give their Navy to Germany.

Churchill called the Admiral of the French Fleet, Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan, begging him to take his Navy to Britain. Darlan vowed never to let Germany get his fleet, and ordered his captains to destroy their ships if the Germans got close.

Churchill did not buy it. Besides, he had to convince Roosevelt that Britain would not surrender. He launched Operation Catapult to seize the entire French fleet.

The Surcouf (then the world’s biggest submarine) lay anchored at Plymouth in Devon. It was boarded by British troops on July 3 at 5:45 AM, but its captain refused to surrender. Violence broke out – killing the ship’s engineer and three British servicemen while leaving the captain severely injured.

Some 200 other French ships in British Ports were taken with no casualties. Also four French cruisers at the British-held Port of Alexandria in Egypt. The rest of the fleet, however, lay in the French-Algerian city of Oran at the Port of Mers-el-Kébir.

Churchill penned a letter to its admiral, Marcel-Bruno Gensoul, giving him three options: sail away with the British fleet; head to a British Port, a French Port in the West Indies, or to the US; or else! He gave them six hours upon receipt of the message to decide.

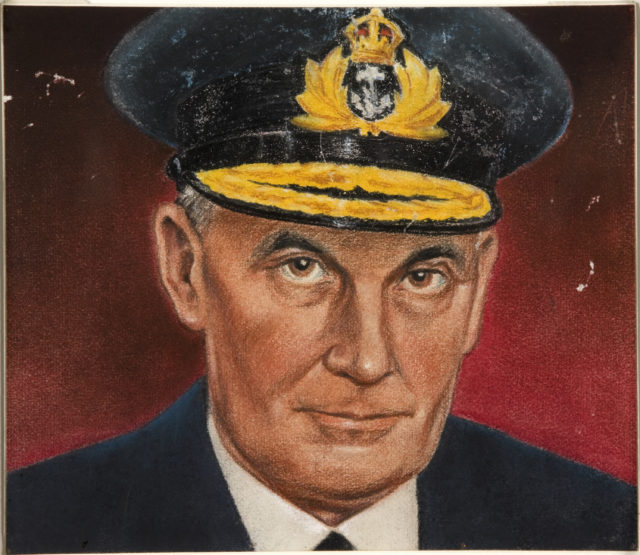

Admiral James Fownes Somerville in Gibraltar was tasked with delivering the letter. He was unhappy and said so to Churchill. Somerville set off with his fleet to Mers-el-Kébir.

French sailors saw them coming at around 7 AM and excitement broke out. They cheered, not understanding what was about to happen.

The British stopped several miles offshore as Captain Cedric Swinton “Hookie” Holland boarded a boat and made his way into the harbor. The former naval attaché to Paris, he was fluent in French and was therefore charged with the negotiations.

Another big mistake. A low ranking officer? Talk to an Admiral!? Gensoul was insulted and ordered the man out of his harbor even though they knew each other. Somerville got into a boat to deliver the message, but Gensoul was still fuming. An underling took the letter at 9:30 AM – setting the deadline at 3:30 PM.

Gensoul contacted Darlan who ordered reinforcements to the port. The British intercepted the message and ordered Somerville to prevent any ship from leaving Mers-el-Kébir. At 1 PM, British planes took off from the Ark Royal and dropped sea mines at the Port entrance.

Gensoul needed to buy time. At 3 PM, he invited Holland aboard his flagship, the Dunkerque, to show him Darlan’s secret orders sent ten days before. Holland contacted Somerville, who relayed his message to London at 4:55 PM.

Churchill’s teletype response was short – SETTLE MATTERS QUICKLY. Holland left Gensoul at around 5:25 PM, claiming it was a cordial farewell.

At 5:54 PM, the British launched the most concentrated broadside attack in history. The French were trapped. The third salvo took out the Bretagne with its crew of over 1,000 men.

A fireball tore through the fuel and ammunition stores, melting the deck. Those who jumped into the sea found themselves in boiling oil. More ships met the same fate, though the Strasbourg battlecruiser and five destroyers escaped and made it back to their home port in Toulon, France.

The firing stopped after exactly ten minutes, leaving 1,297 sailors dead and another 350 wounded – the highest single death toll since WWII began. The French retaliated with an air strike on Gibraltar. Except for some minor damage, there were no casualties.

Roosevelt was impressed and sent Britain 50 warships – all loaded with weapons and ammunition.

In late 1942, Germany had had enough of quasi-independent Southern France. As they advanced toward Toulon on November 27, the French Captains scuttled their ships – all 70 of them. The Germans were upset.

Later that day, Darlan sent Churchill a letter which said, in effect – See? I’m a man of my word. Mers-el-Kébir was unnecessary.

Many have therefore wondered why he did not turn his fleet over to the British.