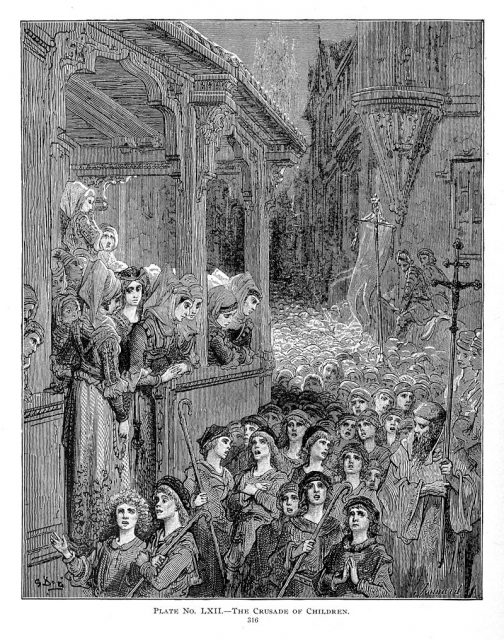

The Children’s Crusade of 1212 is known to have been a disaster, but much about this curious event in history is still mystery. There is only a brief mention of it in the chronicles of the Crusades. Technically, it wasn’t even a crusade as the Pope never officially sanctioned it. What is known, though, is that it was one of the more unusual events of history.

In 1095, Pope Urban called for the first of the crusades. From time to time for the next 300 years, popes would call on their followers to head into Islamic countries and fight the Muslims.

Stephen of Cloyes felt moved, not by the pope but by heaven itself, to lead his followers into the Holy Land to reclaim it for Christianity. According to accounts, he gathered 30,000 followers and headed to Paris in order to gain the support of the king.

Remarkably, he was able to get an audience with the king. All of this is even more remarkable considering Stephen was just twelve years old at the time and his 30,000 followers were just children themselves.

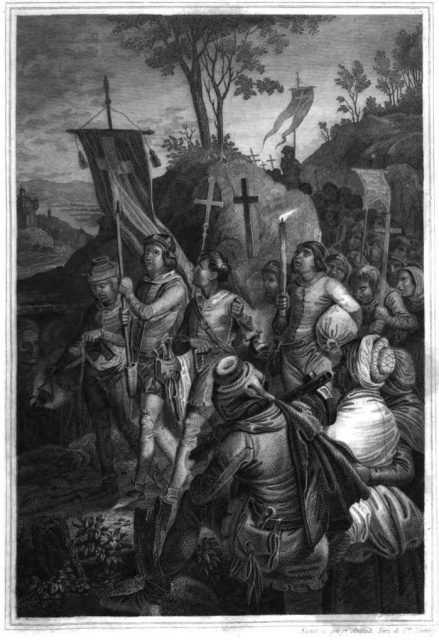

In the meantime, Nicholas of Cologne was leading another group consisting of tens of thousands of adults and children. He believed that he had been told by an angel to start a crusade. So, Nicholas led his group of followers over the Alps on their way to Jerusalem.

Despite the religious fervor displayed by these children and their followers and despite often taking the same vows as those who participated in Papal crusades, the Church saw them as a threat rather than as allies. The fact that one person could inspire such devotion in thousands of people frightened the local clergy and made them afraid that they were losing control of their congregations.

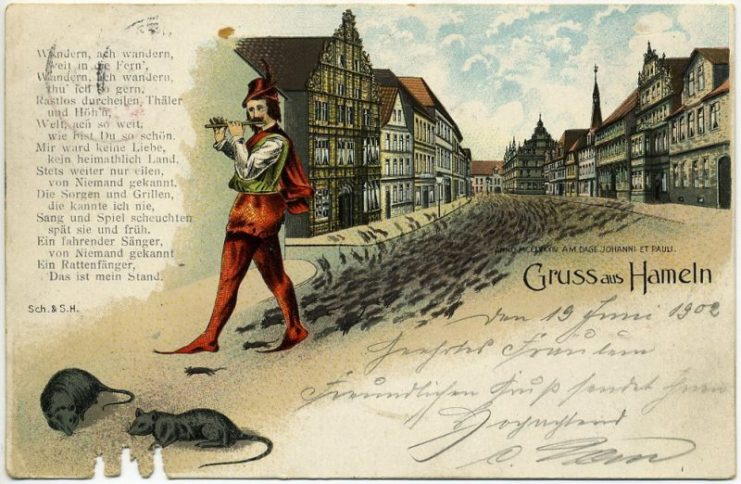

But Stephen and Nicholas were inspiring their followers with songs, sermons, and expectations of miracles. In fact, some consider Nicholas to be the inspiration for the Pied Piper of Hamelin.

As good as the boys were at inspiring fanatical devotion in their followers, they did not fare well in the logistics of a crusade. Nicholas led his group over the Alps and into Genoa, Italy, where the townspeople were not excited to play host to a large group of tired, hungry, religiously fervent children. Stephen’s group met with much the same reaction when they reached Marseilles.

History isn’t clear about what happened to the groups at this point but it appears that they broke up when they reached the coastal towns. Some took local jobs while waiting for a ship to take them to Jerusalem. Some went back home. Some were sold into slavery and some drowned in the sea.

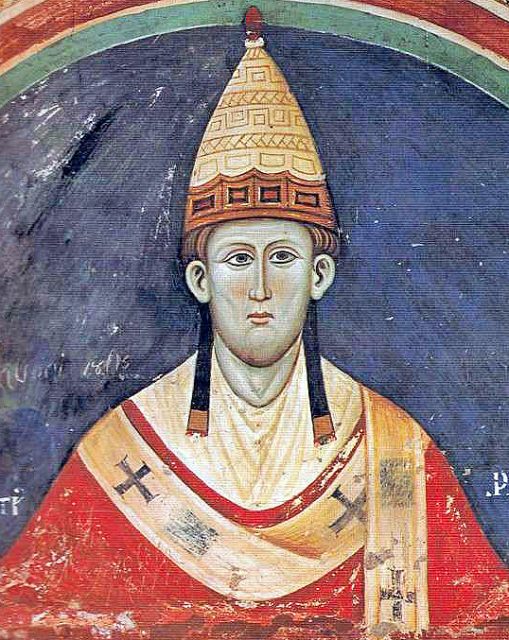

Some say that a group continued on to Rome to receive the pope’s blessing. However, Pope Innocent III praised them for their enthusiasm and told them to go home as they were too young for a crusade.

In 1977, Peter Raedts took another look at the chronicles and determined that those that participated in the Children’s Crusade were the poor and marginalized of society. He believes that they felt that it was up to the poor and marginalized to take over the crusades after the first one failed.

It is Raedt’s opinion that the Children’s Crusade was not made up of children after all but of the poor – which means that even the name of the crusade may be wrong.

There isn’t much in the historical record to confirm whether the participants were children. But there is enough to show that just a few people can persuade thousands to participate in a movement – even one with ineffective or disastrous consequences.