In 1862, the American Civil War was in its second year, and many still believed it would come to a quick end. The Battle of Bull Run showed the American people that battles were not a spectator sport and real guns and real blood were the substance of war. The Confederacy was still fresh and able to fight for their cause.

Little did they know, however, that the war would continue on for three more bloody years, claiming more and more American lives. Everyone was hoping for that last battle which would decide whether the South gained its independence or if the Union would prevail. It was the Battle of Shiloh in the Western Theater that exposed the American people to the true cost of war.

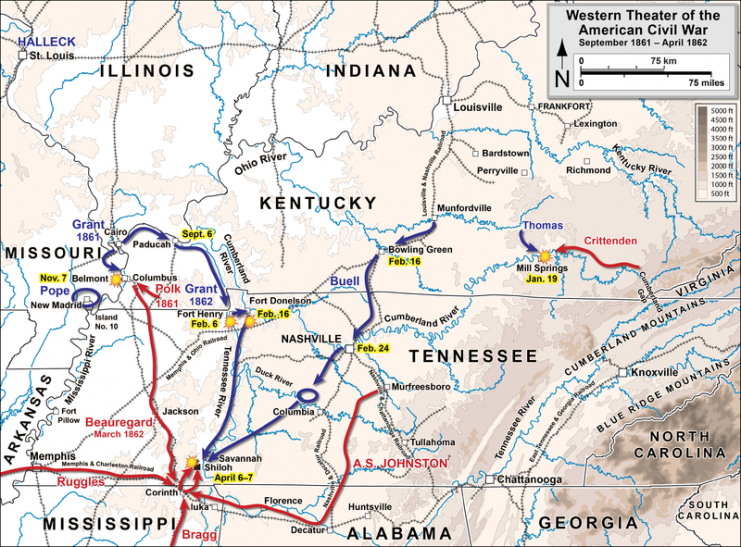

Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck was the commander of the Union Forces in the West. He ordered General Ulysses S. Grant and General Don Carlos Buell, who had successfully moved their armies down the Tennessee River, to head for the major hub of the Memphis & Charleston and Mobile & Ohio railroads. These were located at the town of Corinth Halleck wanted Grant and Buell to destroy the railroad lines.

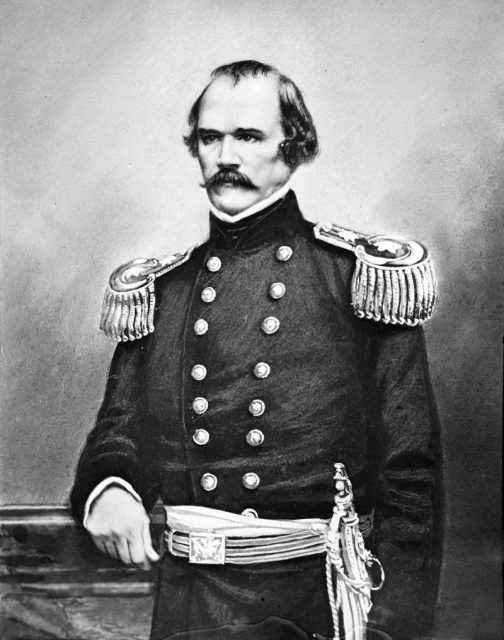

Grant struck camp at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee near Shiloh Meeting House, a small church just west of the river. He was waiting, under orders, for Buell’s forces to join him. However, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston was aware of the Union plan and moved his armies to Corinth to protect the railways.

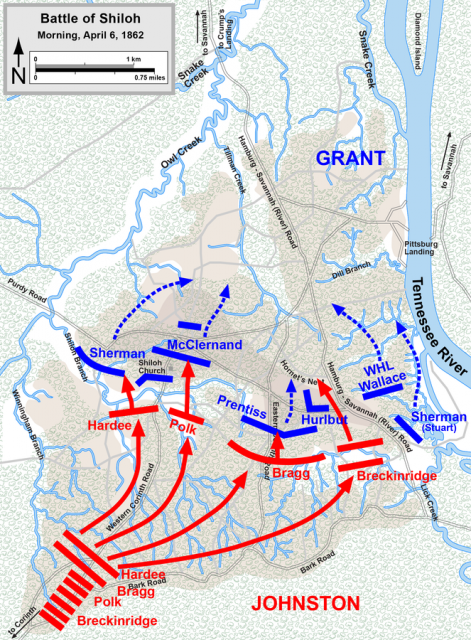

As the sun rose on Sunday, April 6th, some of the Union men were drinking morning coffee while most of the other soldiers were still asleep. Suddenly, they were overwhelmed by Confederate soldiers running out of the woods. Unbeknownst to the Union forces, Johnston had been able to amass over forty thousand men just four miles from the Union camp.

Rumors of the presence of Confederate forces around the town had mostly been ignored, especially by Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, who thought setting up fortifications would worry the mostly new recruits who had never before seen a battle. Tired of the controversy, Sherman mounted his horse to check on the rumors himself and at the edge of the woods came face to face with the Confederate army. The General’s aide was shot in the head, and Sherman was shot in the hand.

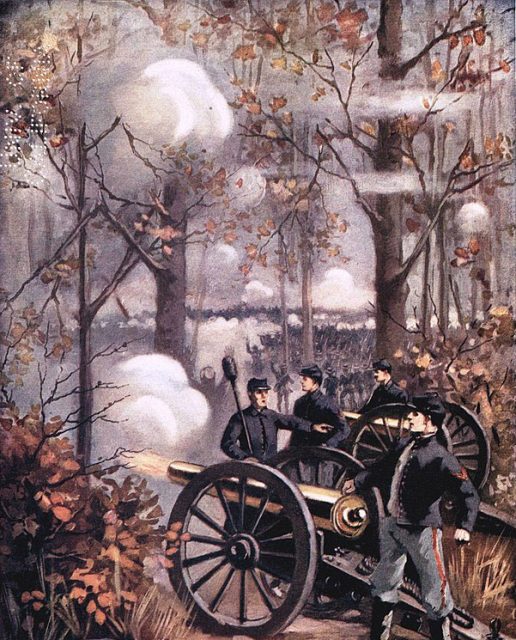

The Union soldiers scrambled to grab their guns and set up a line of defense, but many had not received adequate training and had never even fired their guns. Thousands ran and hid by the river, but those who stayed and fought were continually pushed back, leaving a carpet of dead soldiers and horses in their wake.

The Union army was pushed northward as far as a small wooded area with an old sunken wagon road running through it. General Johnston led a charge on the Union soldiers through a peach orchard that was in bloom. So many bullets were fired that as the blossoms fell among the dead and dying it seemed as though a blizzard surrounded them.

As General Johnston returned to his headquarters, he was struck by a bullet, but when he was helped off his horse no one could find a wound. When the General’s boot was removed copious amounts of blood spilled out revealing a bullet hole through the back of his knee that had severed an artery causing him to bleed to death.

Buell’s army arrived the next day joining forces with Grant and proceeded to push the Confederates back, with the army retreating towards Corinth.

While the battle is listed as a Union victory, more Union soldiers were lost than Confederates. Thirteen thousand Union soldiers and more than ten thousand Confederates were listed as casualties. When the numbers and lists of casualties were published, the public came to realize that this war was not going to be wrapped up with a decisive blow to the enemy. They now knew, as General Sherman had predicted when the Confederacy was born, the conflict would “…drench the country in blood.”