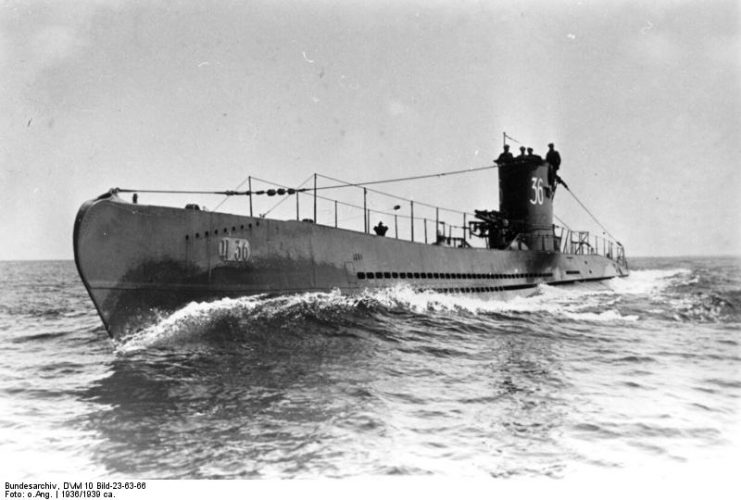

One objective of the Nazi’s strategic plan for dealing with supply ships coming from the United States was to sow fear and panic among the crews of the merchant vessels by sinking them to the bottom of the Caribbean Sea. They sought to accomplish this by sending long-range submarines to operate in the sea and lie in wait for unsuspecting convoys.

In August 12, 1942. US submarine fighters performed a routine sweep of the area between Cayo Hueso and Havana, and they detected nothing amiss in the area. They gave the green-light to a convoy of merchant ships to set sail. The ships included the Manzanillo, the Nicaraguan Guardian, the Julián Alonso, and the tug Humrrick.

Little did they know that German submarine U-508 was awaiting at periscope depth with its engines stopped. Lieutenant Georg Staats gave the order and the Manzanillo was hit by two torpedoes, setting off a huge explosion and sending the cargo ship to the seabed.

Minutes later, U-508 trained its sights on the Santiago de Cuba. The crew tried in vain to escape and a torpedo punctured the hull on the starboard side splitting it in half. All twenty crew members from the Manzanillo and eleven from the Santiago de Cuba died. Sailors studying at the sonar school at Cayo Hueso Naval Base watched the fire from afar.

This was hardly the first time such an attack had happened and wouldn’t be the last. The German Navy regularly terrorized the Caribbean Sea, making it part of the hunting ground for U-boat raiders until the war came to a close.

Among the victims were the cargo ship Nicolás Cuneo, destroyed on July 9, 1942, by a “gray wolf” as Nazi submarines were called. Another two were the Mambi, a merchant ship destroyed by a torpedo on May 13, 1943, and the Libertad, on December 4, 1944. Altogether, seventy-five Cuban sailors died in those attacks, falling prey to the combined attacks of six German submarines.

It became both obvious and imperative that any merchant ship setting sail on the blue waters of the Caribbean needed to be guarded by Allied submarine chasers, but sometimes even they were not enough to mitigate the risk of being sunk.

However, for one convoy of merchant ships sailing from Isabela de Sagua to Havana, it would prove to be enough. The protection of the convoy was tasked to the Cuban submarine chasers CS-11, CS-13, and CS-22, who zigzagged a course two miles from the coast, ten minutes from land and ten from the convoy’s starboard side. It was a hot May day in 1943, when at 5 p.m a US seaplane released smoke signals warning them of a submarine in the area. The submarine chasers alerted the convoy, and CS-13 was ordered to launch depth charges to root out and destroy the submarine.

Their sonar detected something at approximately 1,600 yards, emitting a clean, metallic sound. The submarine chaser launched towards the target, eager for the kill. They caught the submarine by surprise. It had slunk back to lay in wait for the convoy. Conditions were seemingly perfect for the submarine: a completely calm sea and enemy sonar equipment had often malfunctioned in the past. It appeared to have done so again, making detection difficult if not impossible.

But this time things were different and the u-boats chasers closed in. Still, the information had to be perfect if the CS-13 was going to drop the depth charges in the right place. They needed to be within 200 yards.

U-Boat 176’s commander, Reiner Dierksen, realized far too late that he’d been spotted, and tried to escape by performing a full-speed dive to avoid the depths charges. He avoided three out of four of the depth charges, but the fourth one rocked his torpedoes so hard it exploded inside one of his torpedo tubes.

More than fifty crew members died as the German submarine took on water, and dropped to the bottom of the Caribbean. Captain Reiner Dierksen had sunk eleven merchant ships in his career operating in the Atlantic and the Caribbean. For his service, he received the Iron Cross, first 1st class.