A toy tank, handmade cards and even a piece of biscuit that’s almost 100 years old – these are some of the WWI mementos featured at an inspiring exhibit at the National War Museum in Edinburgh Castle.

The National War Museum of Edinburgh has put up a moving display of WWI mementos aged almost one century. These WWI mementos were dusted by their owners’ families and given for exhibit to the museum for the world to see.

And while there are the usual kept stuff most WWI soldiers would save as keepsakes, among the collection are unusual WWI mementos from families of WWI heroes – a sewing kit one WWI soldier carried with him to battle, a piece of biscuit which was given to a nurse upon evacuation and an autograph book full of sketches.

The exhibit of WWI mementos dubbed Next of Kin opened last April 18, Friday, at the said museum and will run until March next year. The objects featured in the collection allows visitors to see a picture of Scotland during the WWI-era. These treasures came from official and even private sources and had been passed from generations to generations among close kin (thus, the exhibit’s name).

As museum curator Dr. Allan Stuart spoke about the exhibit to the Daily Record, these WWI mementos spoke volumes of their owners’ time in the war. Not all who participated in the Great War were killed. Some had lived yet kept silent about their WWI experiences and ordeals. Additionally, only a handful expressed their Great War encounters through writing.

Aside from that, Dr. Allan Stuart further commented about how these WWI mementos being illustrations of how objects – may they be dusting in attics or featured in museums – are more than just things. They have deeper stories behind them and the individuals that kept them.

Here are a few of the WWI mementos displayed in the Next of Kin exhibit.

GEORGE BUCHANAN

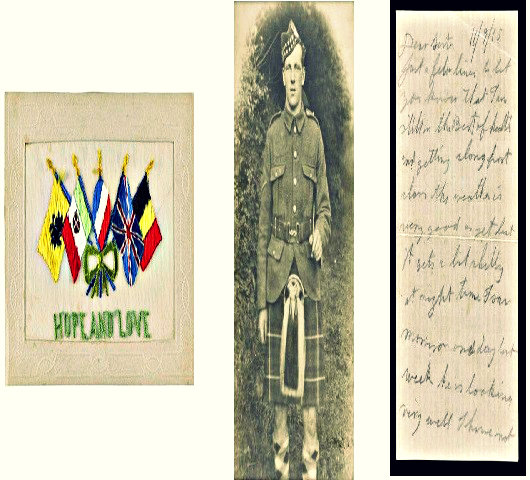

When George sent an embroidered postcard to his sister, little did he and his family know that would be the last WWI memento he would send and they would get.

George joined the Great War as a volunteer in 1914. He was assigned in the 8th Battalion Seaforth Highlanders. Throughout his service, he constantly kept in touch with his mother and sister in Portobello, Edinburgh.

Appallingly, after he sent that embroidered postcard, the next letter his family received was from William Crawford, George’s battalion chaplain. The message confirmed the death of their 27-year-old loved one after being missing in action for a few weeks. He died in the Battle of Loos which saw a major contribution from Scottish soldiers in the front line.

Crawford’s letter, sent two months after the death of George, pointed out the suspense the family might have felt waiting for letters from him. He also attributed the delay of the bad news to the constant shelling of the area where the WWI soldier was assigned. It was only shortly before the letter was sent that George’s death was confirmed and his body was buried in the field. The chaplain assuaged the death by telling his mother and sister that he was one gallant soldier with good character.

George’s family donated to the museum other WWI mementos other than the embroidered postcard. They gave the note he sent with the postcard, the chaplain’s letter about his death, service medals and ribbon as well as a memorial plaque and scroll sent to the family by the British government in behalf of the king.

ARCHIBALD SNEDDON

Archibald Sneddon was initially exempted from being drafted into the Great War when the conscription in 1916 deemed his job at the Beardmore engineering factory in Coatbridge, Lanarkshire a key part in the WWI industry. However, when the need for manpower became great, he became obligated to sign up and he did. Early 1918 saw Archibald being a Lance-Corporal with the 10th Battalion Cameronians.

When he was shipped off to Vimy, France, he etched the date and location in a book of psalms and hymns. The said book was one of the many printed by the Church of Scotland for the soldiers. he kept his copy close to him even while fighting in the Western Front.

When the Great War ended, he kept the book as a keepsake bringing it with him always for the rest of his life. He even took it with him when he emigrated in 1923 to the US.

The book was among the WWI mementos donated by his family to the museum. Others were a telegram sent to him while he was in a military camp telling him that a certain Margaret – either his sister or mother – died, his Tam o’ Shanter beret bearing the Cameronians’ regimental badge and a model tank that according to his family was made by a German WWI POW.

WILLIAM DICK

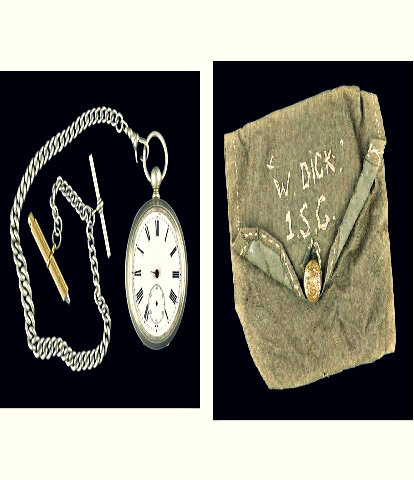

Scottish soldier William Dick’s wife was the recipient of a series of heart-rending letters from his close comrade. The letters informed her that William received serious injuries during battle, had to be amputated and finally, had succumbed to his wounds and died.

The messages, part of the WWI mementos surrendered by the soldier’s family to the museum, were penned by Corporal Stark.

William was with the 1st Battalion Scots Guards assigned in the trenches of Ypres, Belgium when he got wounded in his right leg. His friend wrote that his leg had to be cut off so that he could recover. However, four days after his wife got the letter, another came telling her about his death and added that he had been ready to meet his Creator when it came.

Other than the letters, William’s next of kin gave the fragment of the shell that caused his fatal wound as part of his WWI mementos as well as his pocket watch, a purse with his name on it, the photo of his grave in Belgium and a brass nameplate which determined his barracks bed.

HENRY (HARRY) HUBBARD

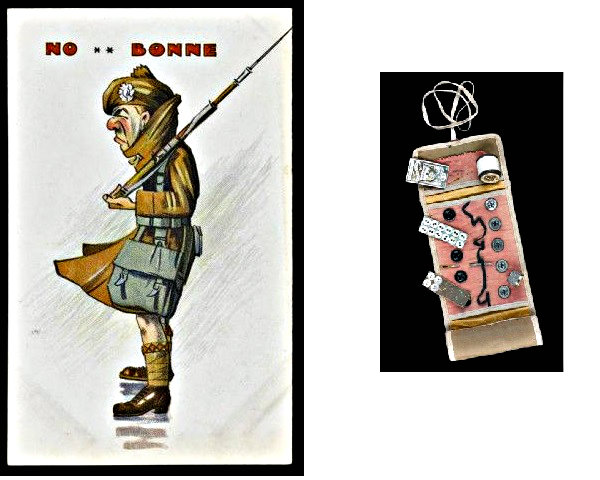

Harry was one of the many WWI soldiers who were discharged from the war because of health complications. Harry had worked as an architectural draughtsman in Glasgow when the Great War broke out. So, he signed up in the 9th Battalion Highland Light Infantry known as the Glasgow Highlanders. This was one of the first units of pre-war part-time soldiers and volunteers to war service to be sent to the Front.

However, his war service was cut short when Harry suffered from carbuncles, poisoned leg and jaundice upon his first winter in the trenches. He had to recuperate in the hospital for a year and four months. After that, he was not able to get into active service again.

Later on, he worked as a draughtsman at the Scottish national War Museum. The said museum is one of the eight locations the Next of Kin exhibit will be going to next after its time in Edinburgh Castle.

Among the WWI mementos his family donated for the display are his autograph book which his mom gave him and which he filled with jokes, sketches and messages from fellow war patients, his sewing kit which he used to mend his uniform in the trenches and his badge issued by the government to soldiers who were honorably discharged for health reasons.

SISTER ANNIE MARIE LOCKE

Perhaps the most unusual piece among the WWI mementos on display is the piece of biscuit kept by Sister Annie Marie from the war. Imagine a piece of food that’s almost 100 years old!

Sister Annie Marie worked as part of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service during WWI.

According to her family, the biscuit was issued to her during a rapid evacuation of a military hospital in August 1914 in the event of the Allies’ retreat. The biscuits were given to patients and hospital staff as they were boarding a train from Rouen to Nantes.

Aside from the piece of biscuit, the nurse kept other WWI mementos – objects given to her by her war patients. These WWI mementos included a rifle bolt found when the British retreated from Mons, Belgium in 1914 and several weapon fragments from Kut, the Mesopotamian Front in 1916 (present day Iraq).

Sister Annie Marie worked with the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh School of Nursing after the Great War ended.

After its stay in the National War Museum in Edinburgh Castle, the exhibit will go on to eight other museums. The said tour is funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund along with the Scottish government as a commemoration of the centenary of the start of the Great War.