On May 10, 1855, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis wrote one of the most bizarre orders in US Army history. Addressed to Brevet Maj. Henry C. Wayne, it stated, “Sir: [you are] assigned to special duty in connection with the appropriation for importing camels for army transportation and for other military purposes.”

Thus began one of the most bizarre military campaigns in American history: the US Camel Corps.

A need for camels?

Jefferson Davis‘ 1855 order came almost 20 years after a Camel Corps was first suggested. In the 1830s, American westward expansion was being severely hindered by the inhospitable terrain and climate faced by settlers.

To help alleviate this issue, Maj. George Crosman suggested implementing a Camel Corps in 1837, as an alternative to horses and mules, who died of dehydration. The idea was dismissed until 1847, when Crosman met Maj. Henry C. Wayne. The latter was also a camel supporter and, together, they moved toward government support on the implementation of a Camel Corps.

Davis was also a supporter of an American Camel Corps, but didn’t have enough pull as then-chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs to get the necessary approval and funding. Although Davis was appointed Secretary of War in 1853, it took an additional two years for the US Congress to agree to the Camel Corps and allot $30,000 to acquire and test a small herd.

Bringing camels to the United States

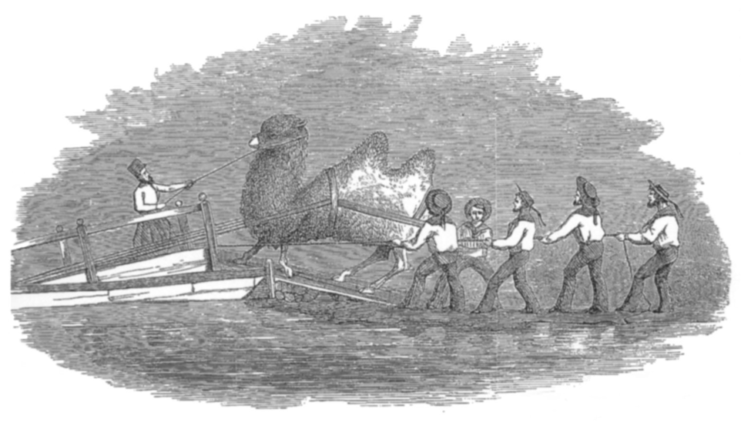

Jefferson Davis wasted no time getting a start on his newly-approved Camel Corps. In June 1855, Henry Wayne departed from New York City aboard the USS Supply (1846), under the command of Lt. David Dixon Porter. After crossing the Atlantic Ocean, they stopped in Malta, Greece, Turkey and Egypt, securing 33 camels.

On February 11, 1856, happy with the animals they’d herded, the pair sailed back for America. The journey home took longer than anticipated, due to stormy weather. Finally, on May 14, the voyage safely reached Indianola, Texas. During the trip back, one male camel died, but six calves were born, two of which had survived. Thirty-four camels total, therefore, arrived on American soil.

Porter was then ordered back to Egypt by Davis to secure more of the animals. By February 1857, the US Army was the proud owner of 70 camels.

Putting the camels to work

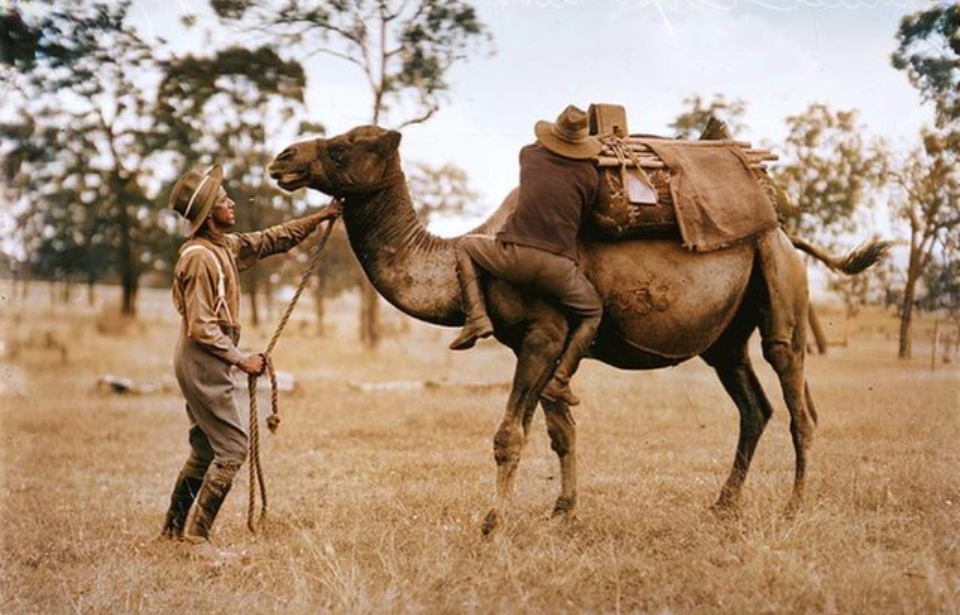

Experiments were done on the original 34 camels to test their strength, while David Dixon Porter was away on his second trip. The US Army wanted to determine their combat capabilities, as well as transportation potential.

While the camels proved their transporting abilities over horses and oxen in the desert, it became clear they weren’t designed for the American style of combat. The most serious drawback was the resistance of both men and officers toward the animals. Compared to horses, they required huge amounts of care. Without it, they developed severe cases of highly-contagious mange, a condition that was unsightly and difficult to cure.

Similarly, camels are a generally docile animals, but they can often be very stubborn. When troops would discipline them for this, it was common for the animals to vomit on them. Furthermore, when they were annoyed with their keeper, they would often bite them.

On top of this, soldiers often complained of motion sickness after riding the camels for any distance or at a gallop, making it hard to use them in combat.

Tensions arise over the US Camel Corps

In March 1857, James Buchanan became US president, making changes that directly impacted the camel experiment. John B. Floyd replaced Jefferson Davis as Secretary of War, and and Henry Wayne was returned to the Quartermaster Department in Washington.

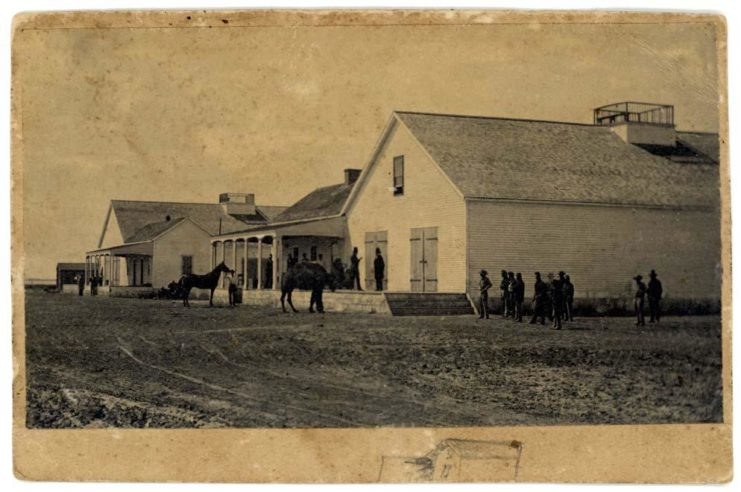

These changes effectively saw the removal of the main supporters of the Camel Corps in one swift movement. However, Floyd still saw the unit as a worthwhile project to continue funding. In an effort to improve frontier travel, he ordered the survey of a wagon road between Camp Verde, where the camels were stationed, and Fort Defiance, New Mexico, on the Colorado River.

Twenty-five camels were included in the survey party. By the time they’d reached Fort Defiance in August 1857, the animals had successfully proven their transportation abilities. Each could carry a load of 600 pounds and outperformed the horses and oxen that had also accompanied this party.

Douglas the Camel and the American Civil War

The American Civil War essentially put a pin in the camel experiment. Early on in the conflict, an attempt was made to use them to carry mail between Fort Mohave (New Mexico Territory) and New San Pedro (California), but this was unsuccessful. Attempts were also made to use the camels as transport, but this was met with limited success, as commanders were often unwilling to deal with the beasts.

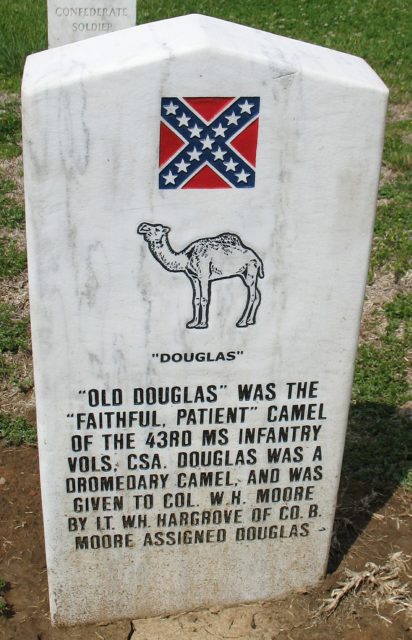

One interesting story of a camel in active service during the war was the case of Douglas the Camel, also known as “Old Douglas.” Douglas, part of the original US Camel Corps, somehow made his way to Mississippi, but the specifics of this journey are largely unknown.

He served alongside the Confederate Army’s A Company, 43rd Mississippi Infantry Regiment. Assigned to carry instruments and knapsacks for the regimental band, Douglas participated in the Battles of Iuka and Corinth. At the Siege of Vicksburg, on June 27, 1863, he was killed by a Union sharpshooter and died.

Douglas was known to break free of his rope, but he usually never wandered too far away from the regiment. However, he had broken his rope on the day he was killed and wandered into no man’s land between the Union and Confederate armies. Today, he’s memorialized by his own gravestone in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Selling off the camels after the American Civil War

Following the American Civil War, the remaining camels were sold off at auction. They became a familiar sight in California, the Southwest, Northwest and even as far away as British Columbia. They wound up in circuses, running in “camel races,” living on private ranches, or working as pack animals for miners and prospectors.

More from us: Project Habakkuk: The British Once Tried to Construct an Aircraft Carrier Out of Ice

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

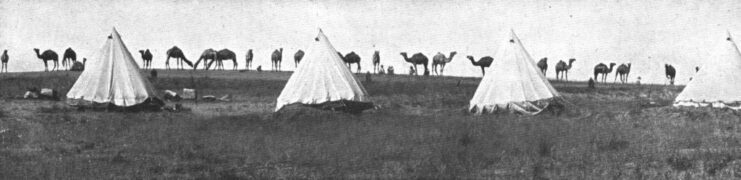

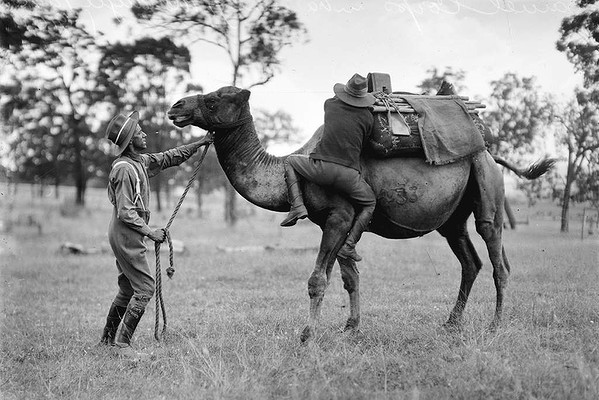

While the Camel Corps in the United States failed, a similar project was undertaken by Britain during the Great War. Established in 1916, the Imperial Camel Corps was a camel-mounted infantry force operating in the Middle Eastern and African deserts. This corps played an integral role in several World War I-era desert campaigns.