Though the British fought the majority of their wars in the 1770s to win and keep the American colonies, these soon became one of their least important priorities. Britain actually placed a higher priority on preserving the rest of her empire, placing a greater focus on the Caribbean, Europe, and the Indian Ocean.

This worked well for the Crown as the losses would have been much greater had they spread themselves too thin in order to try to hold on to everything.

It is a prudent practice of politicians and military leaders to retain a naval force equal to the threats that are on the horizon, whether such threats to your supremacy on the seas actually exist in the present. Sooner or later, someone is going to challenge that supremacy.

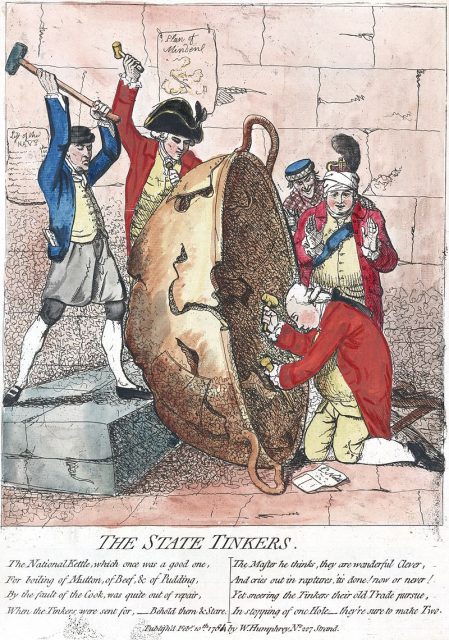

The British prior to the American Revolution are an example of how attempting to save money by scaling back your naval expenses can provide false economies. In fact, when taken to extremes, they can even increase the probability of war. Upgrading your fleet during a war is much more expensive than maintaining it during peacetime.

Britain under King George III shows us a mixture of lessons we can learn from. For one, a naval power can get into trouble by not investing in its navy. That power can correct those mistakes, at least in part, by changing its priorities during a war.

Finally, by making changes after the war is over, it can increase its likelihood of success in future situations. The US can learn from these lessons and avoid major swings in their naval preparedness.

The American Revolution, though originally fought by the British to retain authority in North America, quickly became a true maritime war of which North America was only one theater.

France and Spain were the main rivals to Britain’s supremacy and they allied with the Americans once it appeared they had a chance of winning. France joined on the side of the Americans in 1778, and the Spanish joined the next year. Both were looking to retrieve possessions that the British had taken in previous wars.

By distracting the British in America the French and Spanish could be free to attack in other places around the world. So they supplied the American rebels with arms, stores, and soldiers. The battles that Britain was drawn into were not just on the North American continent but in the Caribbean, the Mediterranean and even in the Indian Ocean.

The British responded by dividing the Royal Navy in an attempt to defend all of their holdings. This led to small pockets of weak defenses which endangered the entire British Empire.

Once the French and Spanish joined the war, the British were forced to consider the American theater as a secondary concern. The British Admiralty had allowed the Royal Navy to deteriorate to the point they were not able to adequately defend all of their territories and their homeland when faced with the combined forces of France and Spain.

At this point, the government of Britain reevaluated their commitments. They determined that the American colonies were not their primary goal. King George III determined that the Caribbean Islands were of the utmost importance, even at the cost of an invasion in the British Isles. Losing the income from the sugar islands would mean the British could not afford to continue the war.

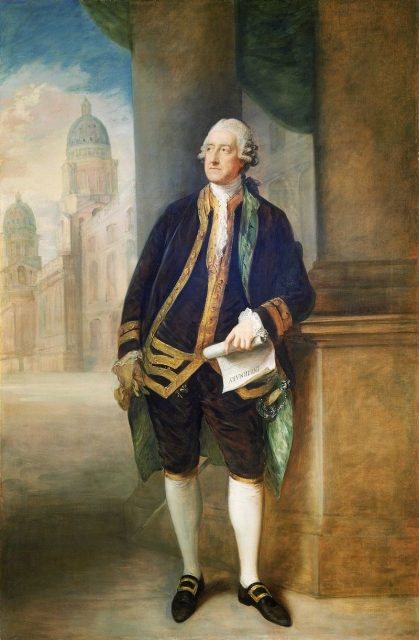

Lord Sandwich, the First Lord of the Admiralty, admitted that the British had neglected to maintain their fleets and had not kept pace with the navies of their enemies. He determined that if Britain had begun updating their fleet sooner, they could have weakened France before Spain even entered the war and thus been able to win in all their battles around the world.

Essentially, the British kept the bare minimum forces in North America to keep that fight going until they could take care of matters in other parts of the world. They were essentially putting off deciding about the American colonies until they could free up resources in other theaters. Of course, history shows that the strategy did not work out in America.