It is estimated that 11 – 20% of soldiers who served in Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Another 12% who served in Operation Desert Storm also suffer from the disorder. Due to the stigma associated with seeing a therapist, many veterans do not get the treatment they need in order to recover from the traumatic experiences they had while serving in combat.

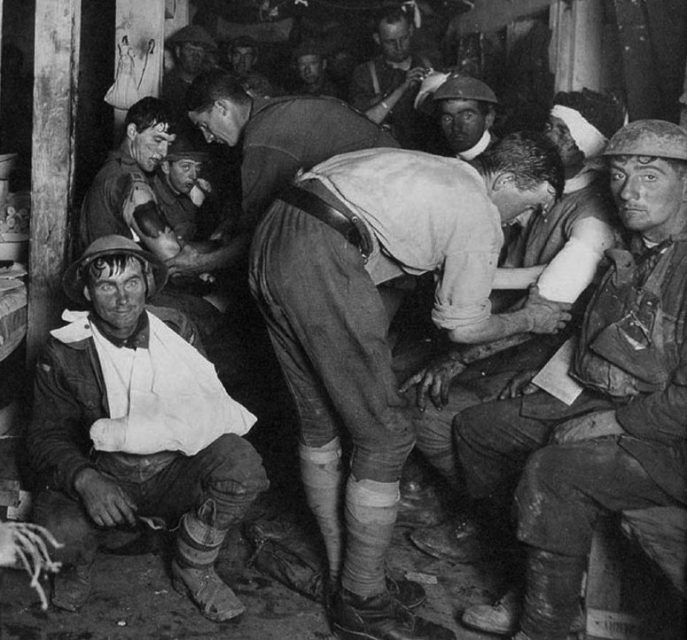

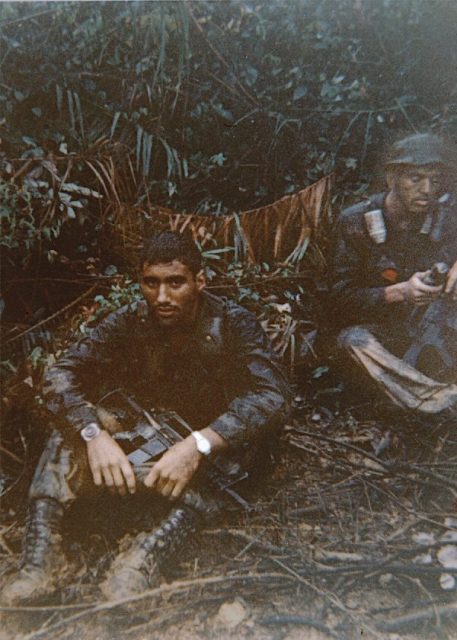

Post-combat PTSD is caused by the fear, death, adrenaline, and danger that soldiers live with for days, months or even years while on deployment. That stress over a prolonged period of time literally changes the way their brains work. They can be left with increased levels of hostility and aggression, raised levels of guilt, paranoia, lack of trust, and an increased likelihood of both depression and suicide.

A new therapy has been developed to help those veterans who are reluctant to see a therapist for their PTSD symptoms. Albert Rizzo works for the Institute for Creative Technologies, University of Southern California, Los Angeles. He and his team are using virtual reality technologies to prevent, identify, and treat post-combat PTSD. Their findings were published in the June issue of Springer’s Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings.

The team was able to match the rise in numbers of soldiers and veterans suffering from PTSD after OIF/OEF to the increasing availability of virtual reality applications that can run on a personal computer. They were able to show that VR can be used to deliver exposure therapy to soldiers returning from combat, which is the preferred method to treat PTSD.

Exposure therapy places returning soldiers in simulations of environments related to their trauma. The intensity of the therapy can be precisely controlled by the therapist with consideration of the patient’s wishes. By using VR, the therapist can provide cues that involve multiple senses and are contextually relevant. This way, the patient can experience the trauma without having to actively remember or imagine experiences that actually occurred.

In order to reenact the types of situations that actually occur in combat, the system contains several scenarios based on accounts from returning soldiers.

The clinical results are promising. In one test, 80% of patients that completed treatment with the VR system showed clinically meaningful drops in PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms. There are additional reports that patients felt improvements in their everyday lives for over three months after completing the treatment.

The team is looking for other uses for their system, including stress resilience training which would allow soldiers to learn coping strategies for the types of trauma they are likely to experience in combat. Rizzo’s team are also looking to use the system to identify which soldiers are mentally and emotionally prepared to return to duty and those who need further treatment or more time to recuperate before being deployed again.

The team feels that the current generation of soldiers is familiar with the technology, having grown up with it their whole lives. Today’s soldiers are often more comfortable with virtual reality applications than they would be with traditional therapies. The team sees a future where therapists are able to use VR to help address the mental health needs of modern soldiers.