At the turn of the 20th century, Canada did not have much in the way of an army. The joke was that only its parliament and railway kept it together. WWI would change all that, giving Canada something else to brag about – one man armies.

Thain Wendell MacDowell was born on September 16, 1890, in Lachute, Quebec, Canada. The only thing that hinted at what he would become was his love (and talent) for sports as he graduated from University with a Bachelor of Arts degree.

He joined the Canadian Officer Training Corps as an Officer Cadet of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada while still in college. After graduation, he joined the 38th (Ottawa) Canadian Battalion – that could have been the second hint.

When WWI broke out, he made his first mark at the Battle of the Somme. Famous for being one of the bloodiest in recorded history, it also proved that Canadians were a force to be reckoned with. Ditto with MacDowell.

The Battle of the Somme began on July 1, 1916, and by the time it ended on November 18, well over a million men had died. For nothing, because the Germans were still in France.

There were many battles during the Somme Offensive, but the one that first put MacDowell’s name in the history books was at the Battle of Ancre. Given how many had already died, public support for the war was waning, so the political pressure was mounting.

On November 13, the British attacked the Germans in the Ancre Valley – hoping to boost morale and gain further ground. The 4th Canadian Division had already taken the longest German trench (the Regina) on November 11, taking over a thousand Germans prisoner.

Desiré Trench was next. Winter’s snow began its debut late on the evening of November 17. By 6:10 AM the following morning, it had started raining again, making visibility awful. It was exactly what the Anglo-Canadians needed.

When they began crossing no man’s land, the rain had turned into a blinding sleet. Too late to turn back. Some companies became disorientated and got lost. Others walked straight into German fire – including MacDowell.

Two machine gun nests missed him, but the third one didn’t. Miraculously, only his left hand got shot, but he kept on going. In the trench ahead, a German soldier squinted, trying to see through the sleet.

He was still doing that when MacDowell’s boot kicked in his face. The bullet that followed must have been a mercy. Other Germans attacked the Canadian, but at such close quarters, rifles were useless.

MacDowell sucked the bullet out of his hand and killed three more in hand-to-hand combat. That convinced the rest to surrender – about 53 men. Fortunately, the rest of the Canadians showed up in time.

He then gave the order to advance further, but his men they told him to shut up and rest. That was the last day of the Battle of the Somme as winter put a stop to any further action.

McDowell was sent back to Britain, where he gave into a severe bout of post-traumatic stress. He was given the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for meritorious service in combat. Then he was sent back to the frontline.

France, again. This time in Vimy, Pas-de-Calais. The French were planning the Nivelle Offensive to break through German lines on the Aisne. They needed a diversion, so the Commonwealth obliged them.

Rising 475 feet at its highest point, Vimy Ridge dominates the surrounding flatlands and was, therefore, the backbone of German positions in France. Five German regiments made up of Bavarian and Prussian troops had held it for two years.

Continues on Page Two

The British and the French had tried to dislodge them, losing thousands of men in the process. On April 8, 1917, it was the Canadians’ turn under Lieutenant-General Sir Julian Byng.

The force of about 97,000 Canadians positioned themselves near the German outposts and synchronized their watches. At exactly 5:30 AM on April 9 (Easter Monday), they pounded the ridge with 983 heavy guns, howitzers, and mortars. People in England (over 100 miles away) could hear it.

After exactly three minutes, the men advanced – all while the firing continued. They had rehearsed this back in Britain but, even so, those marching knew some of them would be hit by friendly fire.

MacDowell’s battalion was deployed to take Hill 145 – also called “The Pimple.” It was not easy. With firing coming from both sides, he reached the first enemy trench just before dawn… 50 yards to the right of his target. Meaning he had missed.

Separated from the rest, there was only MacDowell and his two runners – Privates James T. Kobus and Arthur James Hay. An ambitious man, MacDowell wanted the dugout for his headquarters, so he took out two machine gun nests with well-aimed grenades.

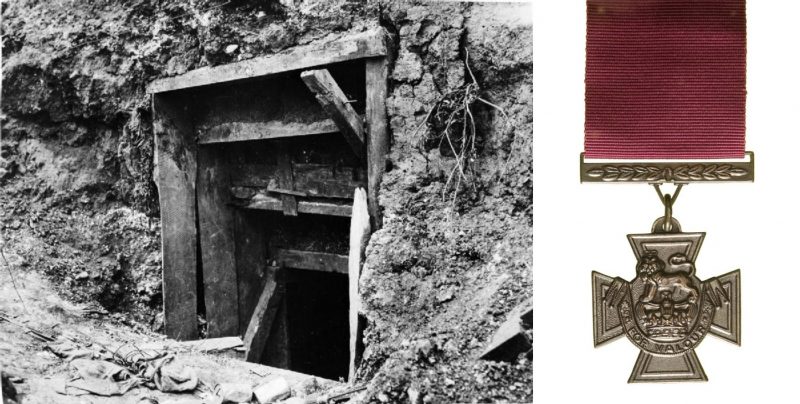

They secured the area, but the dugout went deep underground, complete with a ladder. He yelled down, ordering the Germans to surrender. No response.

He climbed down the 52 steps, rounded a corner, and came face-to-face with Prussian guards. There were more behind them, but the tunnel curved so he could not see them all. They made their move.

So did MacDowell, “Surrender now or die!”

They blinked. MacDowell yelled back up the tunnel, ordering his troops to blast the tunnel with everything they had. Convinced that a vast horde of angry Canadians was up there, the Germans surrendered.

“How many!?” MacDowell barked. Seventy-eight. Great. MacDowell only had two up there. What to do?

“Climb!” he ordered. “But only in groups of 12. Or else…”

The first group did so. Reaching the top, they saw only two men – game over. One lunged for a rifle on the ground, but it was the last thing he ever did. That took the fight out of the rest.

Fortunately, the killing shot echoed into the tunnel below. Grinning, MacDowell motioned the next 12 forward.

Photo Credit

A group of 15 Canadians found them. True, their rifles were so clogged with mud they were virtually useless, but the Canadians wisely kept their mouths shut.

MacDowell became a major for his services and received a Victoria Cross. As for Canada, it gained battle-hardened veterans and the confidence to think of a future without Britain.