Despite the term WWI, the images most people have of that conflict are not of the world but Europeans fighting each other. It is therefore easy to forget that non-Europeans were involved and suffered accordingly. Some were rewarded, however, despite the inherent racism of the time.

Among them was Khudadad Khan born on October 20, 1888, in Dab, Jhelum District, Punjab, British India – now the Chakwal District in Pakistan. Part of the Minhas Rajput people, he was a Kshatriya – a member of the Hindu warrior caste. Although he was Muslim, India’s caste system was so pervasive that it applied to Khan – his destiny was set.

He became a sepoy – an Indian soldier in the British Indian Army. Khan was assigned to the 129th Duke of Connaught’s Own (DCO) Baluchis – today the 11th Battalion of the Baloch Regiment of the Pakistan Army.

There was another reason that many like Khan were eager to serve. They had heard of Europe and wished to see it, but their excitement did not last. As soon as they got to the continent, many wrote back home urging friends and family not to enlist.

The sepoys were more than willing to serve and die for Britain, but they suffered in the cold weather. Indian cooks were usually provided, but the logistics of war in Europe did not always make it possible. Some of the Indians were strict vegetarians – an alien concept to people in Europe, at the time.

However, they were needed. Britain was unprepared for the outbreak of WWI and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) desperately needed reinforcements. At the end of September 1914, the first sepoys arrived at the French port city of Marseilles. From there, Khan traveled by train with his unit to Orléans and was thrown into the frontlines.

Hoping to block the German advance into France, the Allies had dug a series of trenches to keep them at bay. The Germans responded by doing the same, then tried to outflank the Allies by digging to the west of them. Each side dug in until they reached the sea at Belgium on October 19, 1914 – marking the start of brutal trench warfare.

The 20,000-strong 129th Baluchis reached Ypres in West Flanders, Belgium around the same time. They were among the first troops at the First Battle of Ypres. They were also the first Indian regiments to face the Germans who were trying to take the vital ports of Boulogne in France and Nieuport in Belgium – overwhelming the Allied defenders.

On October 29 two Baluchi companies were holding the Allied line at the Flemish village of Gheluvelt in the Hollebeke Sector – now part of Zillebeke. Most of the residents had been evacuated for their safety, but not before they got a look at the foreign soldiers sent to help them fight for their country.

Although by then accustomed to the rain, the 26-year-old Khan was not happy. Being wet was one thing. Being wet, cold, and muddy, was another. He was in a trench to the north of the village, just past the church. Further west of them were Boulogne and Nieuport – places he and his men had never seen but were ready to lay down their lives for.

Nor did the trench offer much protection. They had dug it so hastily it was too shallow. Their only hope lay in the water-logged ground around them. If they were lucky, it would slow the Germans down and buy them some time.

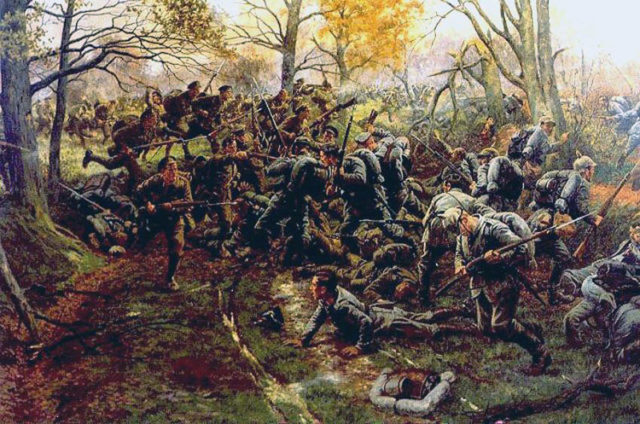

Khan was with the machine gun crew, but that offered little comfort. He and his fellow soldiers had heard of the Germans and knew they had formidable weapons. The 15,000-strong German 54th Reserve Division attacked. The Baluchis had been separated into several units, and as Khan’s group were an auxiliary force whose main task was to buy the Allies time, they were greatly outnumbered five to one.

The Germans had hand grenades while the Baluchis had none. Neither had the 1st South Wales Borderers whom the Baluchis had gone to assist. Some managed to improvise by rigging explosives in hurriedly-emptied tin cans, but it did little good – the Germans were too many and very well equipped. The 2nd Worcestershire Regiment arrived, and by late evening, they had driven the Germans out of the village. Khan felt hopeful, even though the Germans still surrounded the area.

The next day passed somewhat peacefully with sporadic fire, giving both sides a much-needed break. On October 31, the Germans launched a major counterattack – pounding the Baluchis with everything they had. The sepoys fired back, holding their line with rifles and their two remaining machine-guns. They kept their guns in action throughout the day; preventing the Germans from making a breakthrough.

One of the guns took a direct hit from a shell. Khan’s commanding officer, General Sir Garrett O’Moore Creagh (Colonel of the 129th DCO Baluchis) was also hit, and the position was overrun. The Germans poured through the breach – first with grenades, followed by gunfire and bayonets.

Khan was severely wounded, as were the others around him, but he continued firing until he passed out. Thinking he was dead, the Germans left him as they retook the village. The important ports, however, stayed in Allied hands.

When he finally came to, Khan found himself surrounded by the corpses of his friends – he was the only survivor. Later that evening he crawled back to his regiment and became the first Indian to receive a Victoria Cross – Britain’s highest award for military valor. He survived the war and lived until 1971.

The German commander, General von Lettow-Vorbeck, later said the 129th Baluchis “were, without a doubt, very good.”