In 1917, Marcel Duchamp made the art world stand up and notice by signing his name on a urinal. This display was a sensation because it introduced the idea of art as determined and not defined by class, but also closed the distance between so-called high art and low art.

It might be a stretch to call graffiti low-art, but that’s precisely what it is. Anonymous, often vulgar, it nonetheless serves as an enduring record of those who came before, and can often say a lot about not just the person who wrote it, but the types of people and their experiences.

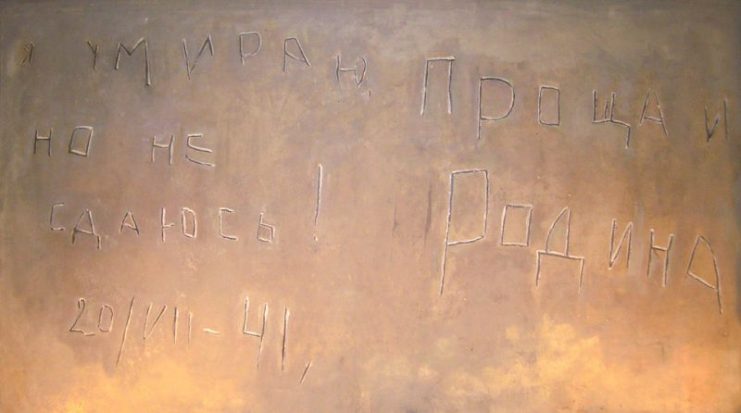

That’s why some say ‘war graffiti’ is important. As long as war has existed, there have been soldiers carving their names into furniture, marking their passage, and leaving an enduring record. Often, it’s the only record of their existence, as it’ done when death can strike without warning and leave no trace that the person ever existed. These images and words exist as a defiant public proclamation of a human being’s existence.

Not unlike the street-level graffiti scrawled across buildings in the inner cities, the drawings of soldiers are part of a culture with its aesthetics, vocabulary, and unique characteristics. American troops from both sides would scratch images and names onto surfaces during the Civil War.

Some of these ranged from common sentiments of what unit was present and their accomplishments to creative insults and curses placed on the enemy, like the polite suggestion that Jefferson Davis should be consumed by a shark that will be eaten shortly after by a whale, who will then go to hell.

Others include requests for prayers. Since towns in Northern Virginia changed hands frequently, soldiers would often have the chance to respond to the graffiti of their adversaries, and some of these exchanges have been preserved in historic homes.

Fifty-two years later, the First World War brought more than a million American troops through France, and they left a plethora of messages and drawings on horses, bunkers, and trenches. However, it was the underground caverns of impromptu barracks where the Americans made their mark, carving their timeless messages into cave walls.

These were silent markers, a document to prove that they existed, before going up into glory, or death. The notes include names, unit designations, animals, the names of hometowns, military insignia, patriotic slogans, names of sports teams and other familiar resemblances of home life.

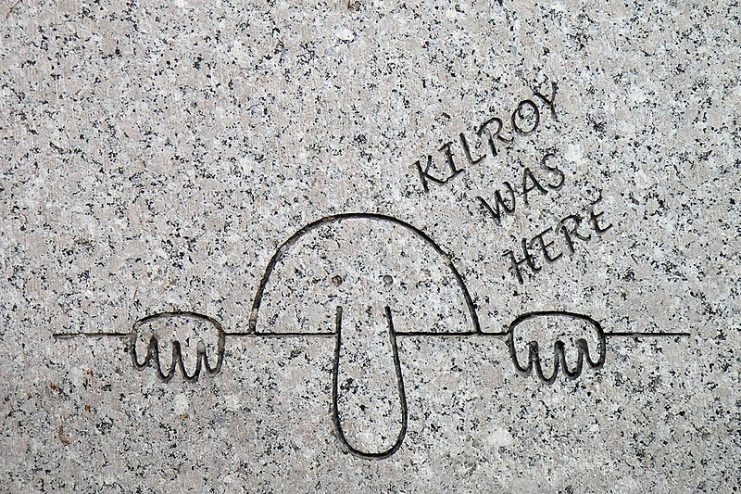

In contrast, the Second World War brought millions of United States troops to European shores, and with them they brought Kilroy. Kilroy could best be described as a communally shared image, asserting himself with the scrawled phrase “Kilroy was here,” which would often be accompanied by a cartoon of a little man with a bald head peeking over a wall, with a large nose and fingers visible.

Kilroy was everywhere. Troops storming a beach or taking a village would discover that Kilroy had preceded them. A perhaps apocryphal tale has Josef Stalin returning from the bathroom during the 1945 Potsdam Conference demanding to know who Kilroy was.

An enterprising G.I had tagged the bathroom. Did Kilroy exist? After the war, several people came forth, including James Kilroy from Massachusetts, who stated that he’d written the phrase on each of the ships he’d worked on as an inspection marker.

Read another story from us: Kilroy Was Here: How A Graffiti Cartoon Bolstered The Troops During WWII

Regardless, he served as a silent guardian, keeping watch over American troops in battle and it’s therefore fitting that there is a Kilroy carved into the stone of the National World War II Memorial in Washington.