The funeral procession was led by a bagpiper, and was attended by a crowd of nearly one hundred people who had come to show their respect for the war hero, Ted Young. Among these attendees were soldiers both in service and retired, members of veterans groups, and even members of the far-off Canadian Royal Navy. The service was conducted by Reverend Jonathan Foster, who had no shortage of information and praise about Mr. Young. Rev. Foster enlightened the crowd of the fact that, while Young’s WWII service was well documented, he had served in the Home Guard when he was only 15, after his first application to join the army was turned down because he was’t old enough.

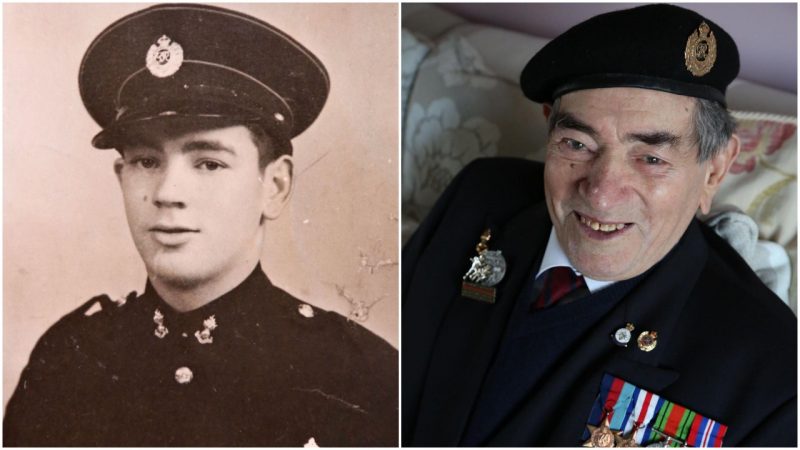

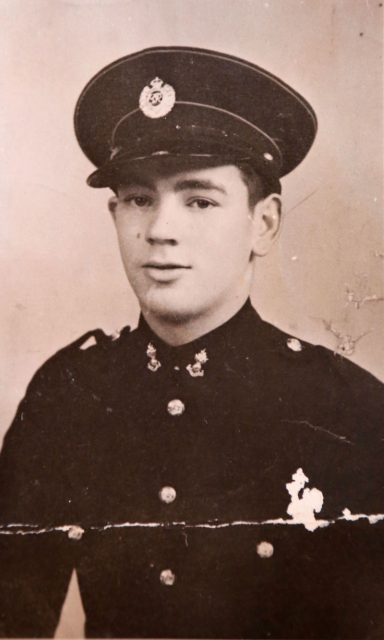

When he was just 17 years of age, a time when most of us are experiencing our first kiss or buying our first car, Ted Young was instead facing German bullets on the beaches of Normandy on D-day. Young had lied about his age to join the Royal Engineers, claiming to be two years older than he was when he signed up. As a result, he found himself swiftly sent to Juno beach on June 6, 1944, where he began his war in the Battle of Normandy.

As part of the Royal Engineers, the infrastructure and tactical construction group for the British Army, Young helped to build landing strips for Canadian spitfires during and after the beach landings. He went on to fight across Europe as the Allies advanced towards Germany, beating the Nazis back towards Berlin. It was in Holland, during Operation Market Garden, that misfortune finally struck the underage hero, who was severely injured, ending his military career in Europe.

Young’s injuries would not, however, cut his life short; he would continue to live on in Great Britain as a hero for 73 years after the end of the war, passing away peacefully at the age of 94. His legacy followed him to the afterlife, as he was given a full military send-off in Poole, Dorset. With a coffin draped in the Union Jack that he had fought under, sacrificing so many years of his youth, and topped with a wreath of poppies, Young was carried to his final resting place by contemporary members of the Royal Engineers from Bovington Camp, Dorset.

Fosters sermon alluded to the horrors that Young saw during his landing on Juno beach, outlining his mingling with Canadian troops, and his task of removing the hedgehog barricades to make way for his fellow soldiers. After Young’s unit was inland and had prepared an airfield, the first pilot to attempt to land was shot down — the planes dislodged propeller flew into a friend of Young’s like a saw, killing him instantly.

Young was initially from Colchester, and after the war he returned there to work for a construction company, before moving to Poole after the death of his wife in 1987. His daughter Irene Richards, who now is 67 and incredibly proud to see the turn out for her father’s funeral, attended his service and contributed readings, as did Major Andy Kerr of the Royal Engineers, who recited his unit’s official prayer. As is standard with military funerals, two minutes silence followed, as well as the playing of the Last Post.

Richards intends to cremate her father and split the ashes, scattering them in two places. One over his father’s grave and the other in Normandy, where he fought so hard.