During the 19th century, China was struggling to maintain its imperial dynasties that had ruled for over three hundred years. The Qing dynasty, established in 1644, saw the population of China increase by over three million people.

In 1735, Emperor Qianlong came to the throne and with his conservative leanings and encouraged book burnings, penalties for homosexuals and encouraged Chinese men to wed only virgins, leaving widows with no hope for marriage in a male-dominated society.

In 1600, the British East India Company was founded by John Watts in London, England, as a small conglomerate of London merchants. The Company was granted a royal charter giving them the ability to monopolize trade with Asia. The British couldn’t get enough of Indian teas, spices, fabric and Chinese silks and porcelain.

The Company paid for these items with wool, metal, and silver. The Company grew in stature and eventually became more than a trading company when the war between Britain and France spilled over to the East in the 1740s. As the Company began acquiring Indian territory, it was becoming a power in itself.

The British ousted local governments and built their own armies with Indian citizens to defend the newly acquired territories. They had negotiated with China for trade but found themselves restricted to only the port of Guangzhou with severe limitations.

As the Chinese had practically no need for imports from Great Britain, the trade market was becoming increasingly more expensive. That’s when the Company found a new commodity which would weaken China considerably.

Opium, which had been used medicinally for hundreds of years, was now becoming a popular recreational substance in China.

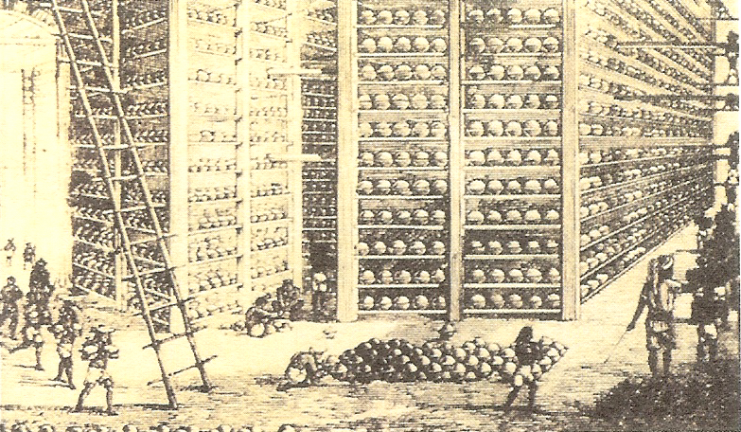

The Company recognized this and began growing poppies, harvesting and processing them into a useable substance and shipping massive quantities of opium from India to China, causing widespread addiction. By 1800, the Chinese government banned the import of opium and had imposed sanctions on those who used it.

The British, more interested in making money than the welfare of Chinese citizens, turned to smuggling. In 1834, the British East India Company lost its monopoly over British opium, leading to price wars and even more opium made its way into China.

The laws were intensified but to no avail and silver was flowing out of the country in return for the opium. Some officials believed that the harvesting and manufacture of opium should be legalized, imposing a hefty tax to make it too expensive. Others, including Lin Zexu, argued that the dealers should be punished rather than the end users.

Zexu verbally attacked the British for victimizing the Chinese on a moral basis and had over one thousand dealers arrested. He required the British to turn over their supplies of opium for which they would be reimbursed with tea. When they refused he put a halt to all foreign trading. Britain attacked that notion on the basis that China was too backward to understand the concept of free trade.

When the merchants began to complain of lost revenue, the British challenged a Chinese warship in 1839, thus beginning the Opium War. The Chinese were no match for the powerful British navy but were able to hold their ground for three years even with commanders who had no experience with war or negotiations. In the end, however, Great Britain prevailed.

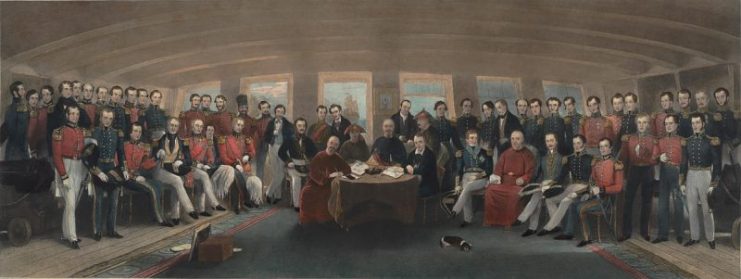

Great Britain wanted to punish the Chinese not only physically but psychologically. The war ended with the Treaty of Nanking in 1842. China lost Hong Kong to the British, who kept control of the city until 1997 when it became a mostly autonomous region but still under the thumb of China.

The Chinese borders were opened to Western religious missionaries, the Chinese were forced to pay reparations to the British, new ports were opened with areas for British officials to live in and be governed by British law rather than Chinese, and any new laws to benefit any Western country would automatically include Great Britain.

The Chinese refer to this period of time when they were oppressed by the British as the “century of humiliation” which caused the incentive for modernization and buildup of military might.

In the words of Professor Miles Maochun Yu, of the United States Military Academy and prolific writer on the military and cultural history of China, “China might have missed the chance to win in the 1840s; will it miss it again in the 21st century in its quest for global domination?”