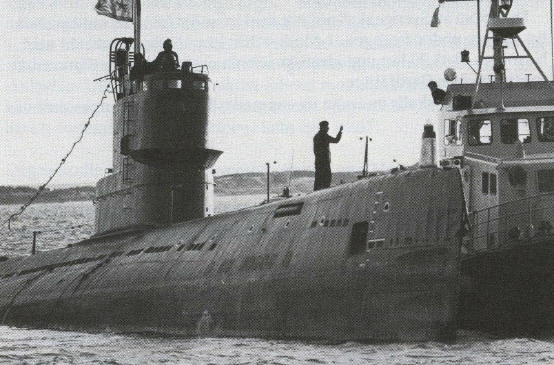

In October 1981, the Soviet submarine (NATO codename: Whiskey) S-363 accidentally hit an underwater rock about 10 kilometres from the main Swedish naval base at Karlskrona, surfacing within Swedish waters. The boat’s presence coincided with a Swedish naval exercise, testing new equipment, in the area. Swedish naval forces reacted to the breach of sovereignty by sending an unarmed naval officer aboard the boat to meet the captain and demand an explanation.

The captain initially claimed that simultaneous failures of navigational equipment had caused the boat to get lost (despite the fact that the boat had already somehow navigated through a treacherous series of rocks, straits, and islands to get so close to the naval base).

The Soviet navy would later issue a conflicting statement claiming that the boat had been forced into Swedish waters due to severe distress, although the boat had never sent a distress signal, but rather, attempted to escape.

The Soviet Navy sent a rescue task force to the site in Sweden, commanded by vice-admiral Aleksky Kalinin on board the destroyer Obraztsovy; the rest of the fleet was composed of a Kotlin-class destroyer, two Nanuchka-class corvettes and a Riga-class frigate. Sweden’s centre-right government at the time was determined to safeguard Sweden’s territorial integrity.

As the Soviet recovery fleet appeared off the coast on the first day, a fixed coastal artillery battery locked onto the ships, indicating to the Soviets that there were active coastal batteries on the islands. The fleet did not turn immediately and as they came closer to the 12-mile (19 km) territorial limit the battery commander ordered the fire control radar into top secret war mode, turning the radar signal from a single frequency to one that jumped between frequencies to stay ahead of enemy jamming.

Almost immediately the Soviet fleet reacted and all vessels except a heavy tugboat slowed down, turned, and stayed in international waters. Swedish torpedo boats confronted the tugboat, which also left.

The Swedes were determined to continue investigating the circumstances of the situation. The Soviet captain, after a guarantee of his immunity, was taken off the boat and interrogated in the presence of Soviet representatives. Additionally, Swedish naval officers examined the logbooks and instruments of the submarine. The Swedish Defense Research Agency also secretly measured for radioactive materials from outside the hull, using gamma ray spectroscopy from a specially configured Coast Guard boat.

They detected something that was almost certainly uranium-238 inside the submarine, localized to the port torpedo tube. Uranium-238 was routinely used as cladding in nuclear weapons and the Swedes suspected that the submarine was in fact nuclear armed. The yield of the probable weapon was estimated to be the same as the bomb dropped over Nagasaki in 1945.

Although the presence of nuclear weapons on board S-363 was never officially confirmed by the Soviet authorities, the vessel’s political officer, Vasily Besedin, later confirmed that there were nuclear warheads on some of the torpedoes, and that the crew was ordered to destroy the boat, including these warheads, if Swedish forces tried to take control of the vessel.

As the Soviet captain was being interrogated, the weather turned bad and the Soviet submarine sent a distress call. In Swedish radar control centers, the storm interfered with the radar image. Soviet jamming could also have been a factor. As the Soviet submarine sent its distress call, two ships coming from the direction of the nearby Soviet armada were detected passing the 12-mile limit headed for Karlskrona.

This produced the most dangerous period of the crisis and is the time where the Swedish Prime Minister Thorbjörn Fälldin gave his order to “Hold the border” to the Supreme Commander of the Swedish Armed Forces. The coastal battery, now fully manned as well as the mobile coastal artillery guns and mine stations, went to “Action Stations”.

The Swedish Air Force scrambled strike aircraft armed with modern anti-ship missiles and reconnaissance aircraft knowing that the weather did not allow rescue helicopters to fly in the event of an engagement. After a tense 30 minutes, Swedish fast attack craft met the ships and identified them as West German grain carriers.

The boat was stuck on the rock for nearly 10 days. On 5 November it was hauled off the rocks by Swedish tugs and escorted to international waters where it was handed over to the Soviet fleet. (via)

Image sources:

Twitter: 1, 2

Emmitsburg.com