The final concerns, wishes, and thoughts of over 230,000 soldiers killed on the front lines during the First World War are being made public online.

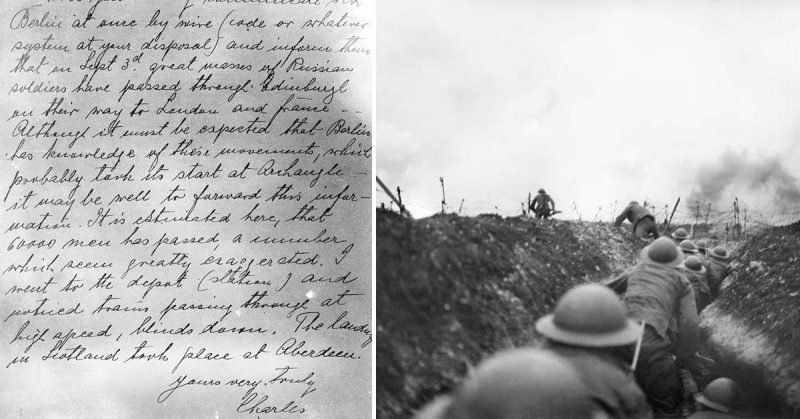

Final handwritten wills were tucked into their army uniforms or kept in their pocket service books.

Those original paper records that survived the passage of time are stored in 1,300 boxes in a temperature-controlled building in Birmingham.

The wills possessed by Her Majesty’s Court and Tribunal Service (HMCTS), are being digitized for the centenary of WWI next year.

The massive online archive is also a portion of a bigger undertaking to make all war wills publicly accessible from the relatively recent Falklands conflict to the Boer War.

The first batch to be made public online includes material of a former professional footballer and the grandfather of rock musician Mick Fleetwood.

The pocketbook of Private Harry Lewis-Lincoln, in addition to a will also contained a letter, possibly to his girlfriend, disclosing on Friday morning they were going straight to Belgium by traveling around the coast, cautioning he wasn’t allowed to disclose the information.

Had the Germans obtained that information disaster could have ensued since they always wanted to be aware of the location of units and troop movements.

Mr. Cooksey said the wills were important documents for descendants to give an impression of what life was like in that period.

The wills provide pieces of information which are filling the voids in a soldier’s service record because it’s about their backgrounds and their place in society, not only about the military perspective.

These men were leaving their families; they were a part of their community, he said.

The first lot to be made available online includes those of a former professional football player and the grandfather of rock musician Mick Fleetwood.

Military historian Jon Cooksey believes the letter would never have been sent out because it was regarded as sensitive material, BBC News reported.

Had the Germans gotten that information it could have been a disaster because they always wanted to know the location of units and troop movements, he said.

The letter also talks about how some troops were anticipating a difficult and lengthy war, a fact that would never have been made public in England so morale would not drop, Cookey explained.