According to an academic’s research, the number of casualties after the First World War went up to ten million, half a million more than what the previous reports stated. French historian, Antoine Prost insists that the previous numbers have been based on error and have been miscalculated.

The mistakes have led the participating countries in the war, to minimize and miscalculate their casualties. He strongly believes, the number of British dead might have been much higher than previously stated.

Antoine Prost, who is Professor Emeritus of History at the Universite de Paris wrote a study in three parts about the First World War. His final volume, the one where he brings up the new 10 million figure, is to be published next week under Cambridge University Press.

For his final volume, Antoine Prost wrote a special article, entitled “The Dead”, where he examines the past figures and shows why he believes there have been miscalculations and errors in establishing the number of casualties for Britain, during the First World War. However, he does emphasize the fact that although it looks like some kind of administrative error, in most of the cases it is just a tendency coming from all parts to try and minimize their casualties after the war, The Telegraph reports.

He also mentioned that most reports contain lists of figures and numbers without giving any explanation on what they mean, what they represent, what they cover and how they were calculated.

According to the French historian, in many instances he was able to detect places where the borders had shifted, failure in recording the deaths of soldiers killed by sickness or servicemen who were killed in prisoner of war camps, and most important, servicemen who were reported missing in action but were never listed as dead if not found after the war.

Most current figures show that Britain recorded 9.5 million casualties in the war, while authour Niall Ferguson uses the 9,450,000 figure in his book, The Pity of War.

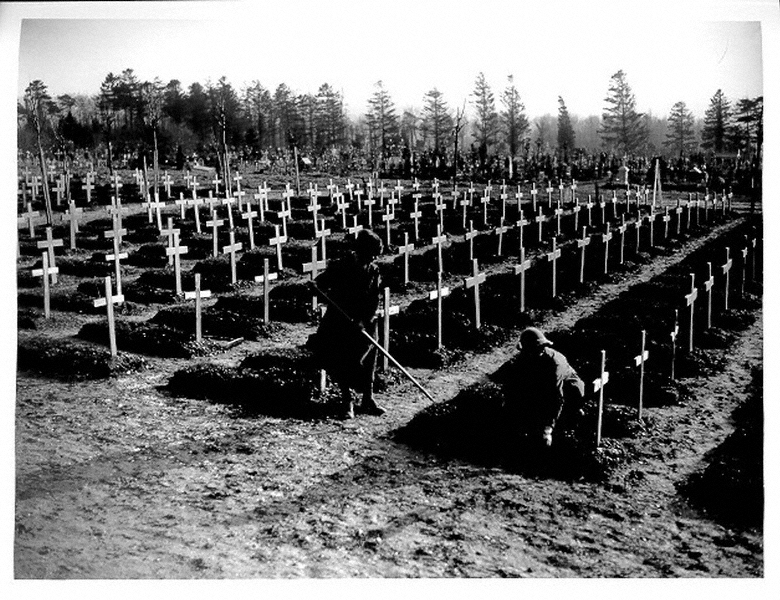

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission honors and preserves the graves of 1,117,091 British and Commonwealth soldiers. The numbers, however, seem to be raising again, as some non-profit organisations have undertaken numerous projects to find the missing soldiers or the unidentified servicemen who didn’t make it on the official records.

“Medical and administrative practices and prejudice led to radical underestimates of shell shock,” wrote Jay Winter, Professor of History at Yale University, in a article for the Cambridge History of the First World War.