Gilbert Horn, Sr. was born in Great Falls, Montana, on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in 1923. To escape the poverty of the reservation, he joined the U.S. National Guard at age 15 and enlisted in the Army at the age of 17 after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

The Native American soldier became a “code talker,” a term usually associated with U.S. servicemen who used their knowledge of Native American languages to transmit coded messages during the world wars. The work of the code talkers remained classified until 1968.

Horn, initially trained as a sharpshooter, volunteered for Merrill’s Marauders, a U.S. Army special operations jungle warfare unit of 2,750 men that became famous for its deep-penetration missions to cut Japanese communications and supply lines in Burma.

The celebrated fighting unit made the 800-mile trek over the Himalayas into the Burmese jungle with only the weapons and supplies they could carry on their teams of horses and mules. The indefatigable unit fought through the monsoon season and debilitating cases of malaria, dysentery, and typhus. Horn, who was wounded four times, was one of 1,200 soldiers who survived the Marauders’ campaign and was awarded a Purple Heart.

In a January 2014 interview with the Great Falls Tribune, Horn talked about his wartime action and said he signed up because he had wanted to “go see the war.” He added, “I didn’t want to be in Montana all my life.”

Of the Burma campaign, Horn said that “there was no support. We didn’t have any artillery. They just kept on knocking us down, whittling us down. It is hard to believe what we had to go through.”

And in June of 1945, when he returned to the Fort Belknap reservation, he said he was “treated like dirt” in spite of his heroic military service. Horn said that few veterans were given the promised preferential treatment when applying for jobs and low-interest federal housing loans.

After he returned to Great Falls, Horn worked on his grandparents’ farm and was educated in business management, psychology, and legal studies. For decades, the decorated veteran served the Fort Belknap Assiniboine Tribe as a judge and council member.

He served on the Assiniboine Treaty Committee for 68 years and was a member of the Fort Belknap Community Council and a tribal judge, during which time he wrote the first regulations for the tribe’s juvenile court.

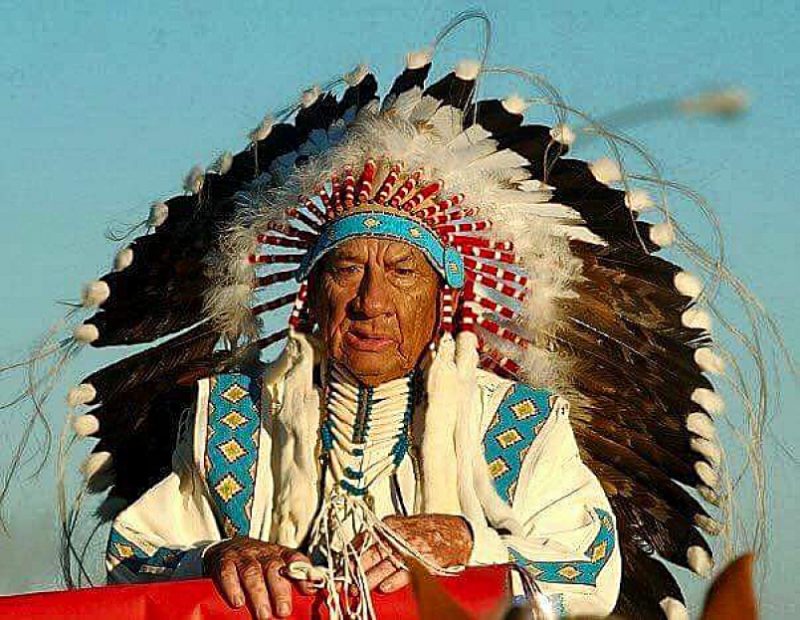

Horn helped to get a Head Start program established on the reservation and, in his honor, one of the buildings carries his Indian name: “Shunk Ta Oba Kni – The Gilbert Horn Sr. Early Head Start Center.” In 2013, Horn received an honorary doctorate in humanitarian services from Montana State University-Northern, and in May 2014, he was named the chief of the Fort Belknap Assiniboine tribe, its first chief in more than 125 years. Horn is survived by 10 of his 11 children, 37 grandchildren, 71 great-grandchildren and 18 great-great-grandchildren.

He was truly a remarkable man.