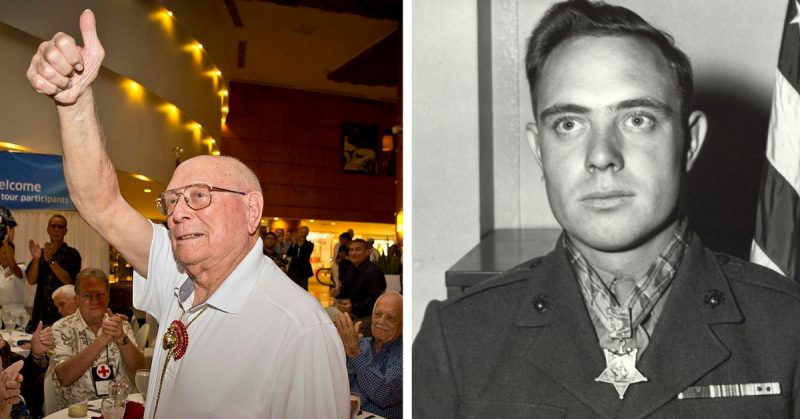

A ninety-five-year-old veteran of the South Pacific theatre of war during World War II is working hard to make sure the soldiers who made the ultimate sacrifice will never be forgotten. Hershel “Woody” Williams from West Virginia served as a Marine in the 21st Marines, 3rd Marine Division, and saw action in the Battle of Guadalcanal, Guam and Iwo Jima during the winter of 1945.

In 2010 he set up the Hershel Woody Williams Medal of Honor Foundation. His goal is to establish a Gold Star Families Memorial Monument in each state along with scholarships for Gold Star children and schemes to educate people about Gold Star families. A Gold Star family is one who has lost a member in the line of duty. During the war, Williams felt “consideration and recognition of the families of those lost in the war was very inadequate.”

Williams had a tough time getting into the service after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. First, he was underage, and his mother refused to sign for him. Undaunted, he attempted to join the U.S. Marine Corps when he turned eighteen, but at five foot six, he was unable to meet the height requirement to enter the Marines. However, due to the heavy losses of personnel by 1943, the Marines relaxed their requirements and Woody was accepted. He trained for about six months in Guadalcanal, fought the Japanese in battles there and at Guam and was then sent to Iwo Jima.

Iwo Jima was a difficult battle lasting about a month because the Japanese forces were so firmly established. They used manned pillboxes, compact structures made of concrete with small, usually horizontal openings for the Japanese soldiers to shoot through. They were so well protected by these pillboxes they were able to destroy most of Williams’ platoon with no danger to themselves. Finally, the Marines came up with a solution. They asked Williams if he would use a flamethrower to take out the pillboxes one by one. When Williams agreed, they strapped a flame thrower pack on him and ordered him to creep along the ground toward each pillbox with cover fire by four other Marines. When he reached the pillbox, he crouched near the opening and aimed his flamethrower into the pillbox killing everyone inside.

Initially, Williams was highly successful, but when the Japanese caught on to what was happening, he became a primary target. When he ran out of fuel, he had to crawl back behind the lines to retrieve a new pack. Oddly, Williams is unable to remember how many times he went back for more fuel and how long he was engaged in using the flamethrowers. He was told that he had used six flamethrowers in the four hours it took to accomplish his task. He has no idea how many Japanese succumbed to the fires he was starting in the pillboxes and says he is not interested in finding out.

Williams rejoined his unit and continued to fight until he was wounded. He received the Purple Heart for his bravery. When the war ended, Williams was recognized with the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions at Iwo Jima which was presented to him by President Harry Truman.

Williams began to suffer from PTSD soon after returning home. At a time when the condition was not even recognized, much less treated, he struggled with his inability to come to terms with his experiences in the war. At first, he turned to alcohol for self-medication, but with his wife’s encouragement, he attended church with her and finally found peace with his acceptance of God. He spent the next thirty-three years helping fellow veterans at the Veterans Administration.

Of his Medal of Honor, which he donated to the Pritzker Military Museum and Library, Williams remarked, “This Medal really does not belong to me—I could not have received it without the assistance of other Marines. So when I wear this Medal I don’t wear it for what I did; I wear it in honor of two Marines—I don’t know their names—who gave their lives protecting mine. It really belongs to them; I’m just a caretaker of it.”