Stephen Harding tells about his book “The Last Battle” which will be turned into a major motion picture, and upcoming projects.

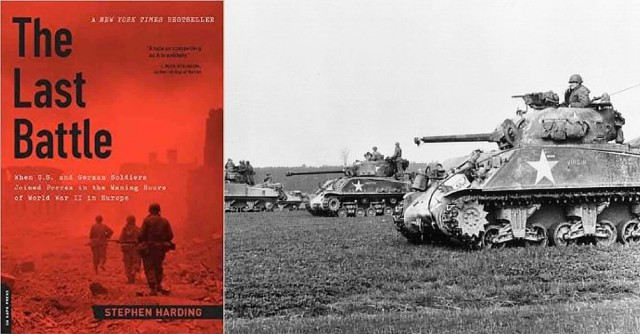

Please tell us the background to your best-selling book “The Last Battle.”

I first heard the story of the battle at Castle Itter more than 30 years ago, while I was working as a staff historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Washington, D.C. I knew it would make a great book, but jobs, family and other projects meant that I didn’t get around to beginning the necessary research until about 10 years ago. Fortunately, I was able to track down and interview the few surviving participants both in Europe and the States, and also found a treasure trove of official documents, letters and newspaper stories. Then it was just a question of finding the time to sit down and write the book.

How did you pick up on the story covered in your new book “Last to Die”?

While co-writing a book on the American B-32 Dominator—a little-known World War II heavy bomber—I came across the story of Anthony Marchione. He has the sad distinction of being the last American killed in combat in World War II, and the fact that his death could well have resulted in a third atomic bomb being dropped on Japan raised his story from an interesting but very personal one to something much bigger and of much greater importance. I was able to find his two sisters, who shared a wealth of documents and other materials with me.

With so many of the major events from the war having been done to death, how much of a challenge is it finding “untold” or “forgotten” stories from World War II?

It is very challenging, because the smaller stories have long been overshadowed and many of the pertinent records have either been misplaced or destroyed. That said, once you know where to look, there are often enough surviving documents upon which to base further research. There are many, many more stories to be told; I doubt we’ll ever run out of material.

While it is silly to ponder how many more there might be worthy of a good book, can you see a point when there are very few left to tell?

We’re obviously losing more and more World War II veterans each day, which of course means that we can’t hear their stories first-hand. But their family members often have letters, journals and official documents that can be very helpful in fleshing out a particular event. Historians, like journalists, have to be adept and finding and using multiple sources to tell a coherent and accurate story.

Is there an event or personality from military history you would particularly like to write about?

I’m researching several topics at the moment, and they all share a few common aspects. They’re all World War II stories, because that is the period I’m most familiar with and the one that most interests me; they each deal with a little-known event, because I like to tell fresh stories that people haven’t already heard a hundred times; and they each focus on a single person, or a small group of people, because I think you can tell a more complete and engaging story that way, rather than trying to write a much broader account about the actions of thousands or even millions of people.

What are you reading at the moment? Do you get time to read many books?

As both an author and the editor of a leading military history magazine, I do a lot of reading, but it’s mostly for research or to fact-check submitted articles. I don’t often get to do much “recreational” reading, but when I do I enjoy the novels of my friend Alan Furst and of writers like Wilbur Smith and Bernard Cornwell.

There are a number of former service personnel who have built successful careers as writers once they return to civilian life. How would you assess your own writing career in terms of the influence your military career has had on your understanding and knowledge for what you do?

As a soldier I was initially an infantryman, and that gave me a working knowledge of small-unit tactics, weapons and the “grass roots” of military operations. After recuperating from serious injuries I sustained in an armored vehicle accident in Germany in the 1970s, I was retrained as a print, radio and TV journalist.

For most of my adult life I worked as a civilian reporter covering military operations in places like Israel, Northern Ireland, Bosnia and Iraq, and my early military training and understanding of military operations were immensely useful.

As a veteran journalist covering conflicts around the world, do you have any experiences you wish to share that you would say have had a profound impact on you?

I saw and experienced many things that affected me deeply, but among the most profound were scenes I witnessed in and around Sarajevo just after the siege ended. I had lived for several years in Heidelberg, Germany, and I was struck by the similarities between that city and Sarajevo—geography, architecture, and so on.

Except, of course, that while Heidelberg had survived World War II intact, the Sarajevo that I spent time in had been battered by years of intense fighting and was almost totally in ruins. They were still finding and burying the dead, landmines were still a constant threat, and the Chetniks still held the high ground around the city. I had been in war zones before that, and have been in others since then, but Sarajevo left a mark on me that nowhere else has.

How would you assess the standard of military history writing and military journalism/writing in general at the moment? What are the challenges facing journalists and writers today?

I think that most of the journalists now covering military operations know very little about the military, and that shortcoming adversely affects the quality and accuracy of their reporting. While few reputable news organizations would cover the World Series using a reporter who knew nothing about baseball, it is fairly common for journalists who are sent to war zones to know nothing about military operations.

As a result, they often don’t understand what they’re seeing or hearing and, if they’ve never before been in a conflict zone, often unknowingly place themselves or those around them in greater danger than might be necessary. All this means, of course, that it’s always better to have military-savvy journalists covering the military, because it makes for more balanced and accurate reporting.

What do you think of military museums and do you favour any in particular? Do you think the gradual shift towards interpretation rather than an emphasis on artifacts, dates, facts and details is a good thing?

I think museums of all kinds serve a vital purpose, in that they educate people about subjects to which those individuals might otherwise never be exposed. Military museums, when done well, can be especially educational and entertaining. While I have enjoyed many military, maritime and aviation museums, my two particular favorites are the Imperial War Museum in London and the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Virginia.

Both institutions use a mix of static displays and interactive, interpretive presentations to educate and entertain visitors. Both are excellent, and I highly recommend them.

Do you have a favourite battlefield or military history related location you would wish to recommend to our readers?

There are many, of course, all over the world, but a visit to Pearl Harbor can be especially rewarding, especially for Americans. The area is relatively compact, and within just a few miles you can visit multiple sites tied to the 1941 Japanese attack and to the Pacific War in general. There are several excellent museums, historic vessels such as the battleship USS Missouri—on whose deck World War II officially ended on September 2, 1945—and, of course, there is the USS Arizona Memorial. And, finally, Hawaii is one of the most wonderful spots on earth to visit.

How do you feel about the possibility of your work being made into a movie? Do you have an opinion on recent “war” films and TV mini-series?

I am thrilled that France’s StudioCanal and The Picture Company of Hollywood will be turning “The Last Battle” into a major motion picture. It’s an amazing true story, and one that is ideally suited for the big screen. Moreover, my forthcoming book “The Castaway’s War”—the true story of an American naval officer shipwrecked alone on a Japanese-held island in 1943—is already attracting interest from major filmmakers, and I hope it, too, will become a motion picture.

Like many people, I think “Saving Private Ryan” is possibly the best “war movie” ever made, and I believe that “Band of Brothers” and “Pacific” have set a very high standard for the TV mini-series genre. The forthcoming “Masters of the Air,” based on the wonderful book by my friend Don Miller, should also be excellent.

We would like to thank Stephen Harding for his time and we highly recommend his books!