Some of the weirdest facts from WWI, the French built a fake Paris to confuse German Night bombers, a pigeon that saved almost 200 American lives and much more!

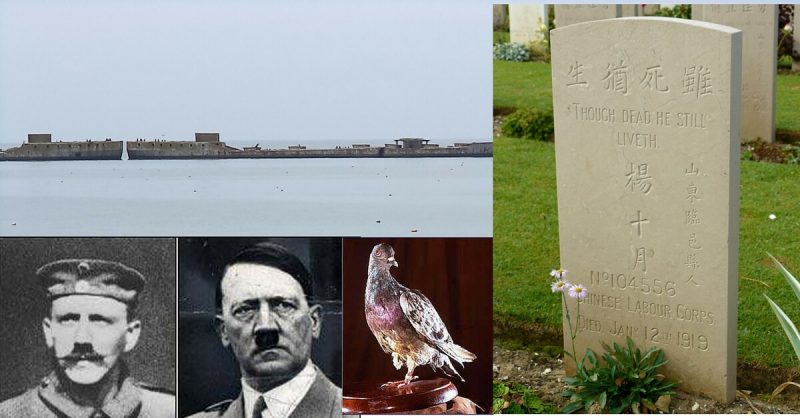

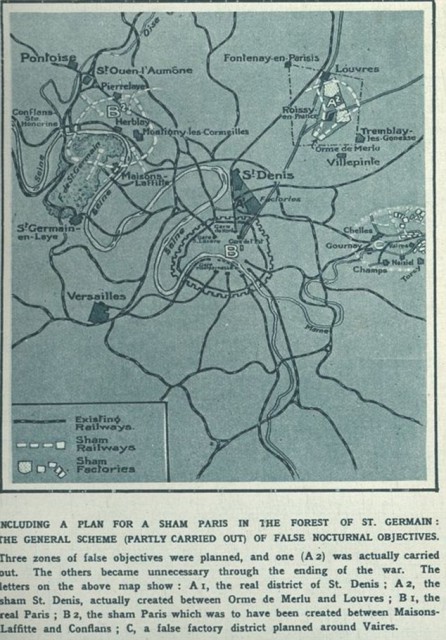

1. A Fake Paris was Built to fool German Pilots

Near the end of the First World War, military planners believed that German pilots could be deceived into destroying a replica city rather than the real one. According to archives revealed by Le Figaro newspaper, a second Paris, which included a replica Champs-Elysees, was built to fool the pilots of German bombers.

The French military thought they could attract the German night bombers away from the real Paris by building a fake city that included countless bright lights.

The replica city would be situated on the northern outskirts of the real Paris. The bogus city contained duplicate buildings, imitation streets lit with electric lights, and even a replica copy of the Gare du Nord train station.

Red, yellow and white lanterns were also used to create the effect of machinery operating at night, while fake trains and false railway tracks were also partially lit. Unfortunately, the fake Paris didn’t get finished before the last German bombing run on Paris in September 1918, meaning it was never tested.

2. Spring Tyres were used in Bicycles by Germany

Soldiers inspecting a battered German bicycle with tires made of springs due to the rubber shortage in World War I.

3. Urinated Handkerchiefs To Survive Gas Attacks

In 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres, the Germans use gas against the Canadians for the first time in WWI. Another gas cloud was released by the Germans on the morning of 24 April wich floated towards the Canadian line just west of St. Julien.

The troops were told to urinate on their handkerchiefs and then place them over their nose and mouth. These countermeasures proved insufficient and thousands died, German troops were able to the village

Allied troops were supplied with masks of cotton pads soaked in urine, after the first German chlorine gas attacks because the pads neutralized the chlorine.

The soldiers were to hold the pads over their face until the gas dispersed. Soldiers found it difficult to fight like this and better means of protection against gas attacks were quickly developed.

4. A wounded Pigeon saved lives of more than 198 US Army Men

During the Battle of the Argonne, in October 1918, ‘Cher Ami’, a female homing pigeon, which means “dear friend” in French, helped save the Lost Battalion of the 77th Infantry Division. ‘Cher Ami’ was a homing pigeon used in World War I by the U.S. Army Signal Corps in France.

Trapped behind enemy lines without food or ammunition, Major Whittlesey and more than 500 men were hunkered down in a small depression on the side of a hill. And they were also taking friendly fire from allied artillery that had no idea they were behind enemy lines. This event was on October 3, 1918.

As the Germans troops were surrounding them on the first day, many were killed and wounded, and as the second day was drawing to an end, just over 190 men were still alive. Major Whittlesey was dispatching messages by carrier pigeons. As they were dispatched two pigeons were shot down and only one carrier pigeon was left, “Cher Ami”.

The message she carried in a container on her left leg read as follows, “We are alongside the road parallel to location 276.4. We are taking friendly fire; from our own artillery, directly on us. For heaven’s sake, you must stop.”

As ‘Cher Ami’ was sent to fly back home, she rose out of the bushes. But the Germans saw her and opened fire. ‘Cher Ami’ was flying through a hail of bullets for several moments. ‘Cher Ami’ eventually was wounded and shot down, but managed to take off again. The loft she was so desperately trying to get back to was at division headquarters 25 miles to the rear.

She made it in an astonishing 25 minutes; a mile a minute while wounded! As this turned out to be the last mission, ‘Cher Ami’ delivered the message helping to save the lives of the 194 survivors, despite being covered in blood, blinded in one eye, having been shot through the breast, and with a leg hanging only by a tendon.

‘Cher Ami’ instantly became the hero of the 77th Infantry Division. Army doctors worked desperately to save her life. They couldn’t save her leg, so a small wooden one was made for her.

When her wounds healed and she recuperated enough to travel, ‘Cher Ami’, now only with one leg was put on a ship leaving France headed to the United States and General John J. Pershing was present to personally see ‘Cher Ami’ off, as she departed from France.

5. Hitler had a full sized mustache, but that got trimmed down

The toothbrush mustache sported by Adolf Hitler’s was the feature that made him instantly recognizable. But he did not always have his mustache like that, in WWI he sported a full handlebar mustache complete with twisted ends. During a gas attack on his trenches, Hitler discovered that his nice mustache prevented his gas mask from sealing tightly.

Logic overcame his vanity, and he decided to trim his mustache. He must have liked it, he kept it that way until the very end.

6. Chinese laborers were used en masse by Britain & France

During World War I, the British government recruited a workforce known as the Chinese Labor Corps. They were recruited to provide support work and manual labor, which allowed the allied troops to carry out front-line duty.

The French government also enlisted many of these Chinese laborers. In total, there were approximately 140,000 men assisting both the British and French forces before the war ended. After the war, between 1918 and 1920, most of these Chinese laborers were sent back to China.

The workers, mainly aged between 20 and 35, were tasked with carrying out essential work to support the Frontline troops, such as repairing roads and railways, building dugouts, digging trenches, filling sandbags and unloading ships. They performed labor duties in the rear echelons or helped build munitions depots.

During the war effort, Britain and France estimated that ten thousand of the Chinese Labor Force was killed; casualties of land mines, shelling, the worldwide flu epidemic, or inhumane treatment. Chinese authorities are contesting these numbers, claiming that the number of deaths was as high as twenty thousand.

7. Shortage of steel forced the use of concrete ships

The first self-propelled Ferro cement or reinforced steel ship intended for ocean travel was launched by Nicolay Fougner of Norway on August 2, 1917. Called the Namsenfjord, it was a 400 ton, 84-foot vessel.

Because of the success of this ship, in October 1917, the U.S. government invited Fougner to head a research into the viability of building concrete ships in the United States.

When the research study was completed, the U.S. government ordered additional concrete-reinforced steel (Ferro cement) vessels.

During the late 19th century, there were concrete river barges all over Europe and because of steel shortages during both World War I and World War II; the US military ordered the construction of ocean-going ferroconcrete ships, the largest of which was the SS Selma.

There were very few concrete ships completed in time for World War I wartime service, but by the time WW II arrived, especially during 1944 and 1945, concrete ships and barges were used to support invasions in Europe and the Pacific by the British and U.S. troops.

8. War work turned some women’s skin yellow

It is sadly something you might see in reimagined Wizard of Oz – girls in ruffled hats, full skirts, puffy sleeves, and Peter Pan collars topped by golden faces and bright yellow, orange, or red hair. They were called The Canary Girls. Not only did they have to abide these odd looks, but the children they gave birth to during this time often did as well.

This was a disturbing side effect to working in munitions plants in WWI Britain. The TNT caused workers’ skin to turn yellow. Because the boys were off at war, most of the plant workers were women, and so those suffering from this peculiar aberration became known as The Canary Girls.

Munitionette Caroline Rennles later recalled:

“So it was all bright ginger, all our front hair, you know. And all our faces were bright yellow – they used to call us canaries . . . some of them used to look at us as though we was insects, know what I mean? And others used to mutter, ‘Oh well they’re doing their bit.’

As I say, some were quite nice and others, you know, used to treat us as though we was scum of the earth. ’Course we, all our clothes like, we couldn’t wear like good clothes because the powder used to seep into your clothes, know what I mean?”

The effects were more than cosmetic. Many women complained of nausea and skin rashes or hives. Some had coughs or chest infections from TNT poisoning. According to a TNT factory worker quoted in Katie Adie’s 2013 book, Fighting on the Homefront, “You expected to feel ‘poorly’; our skin was perfectly yellow, right down through the body, legs and toenails even.”

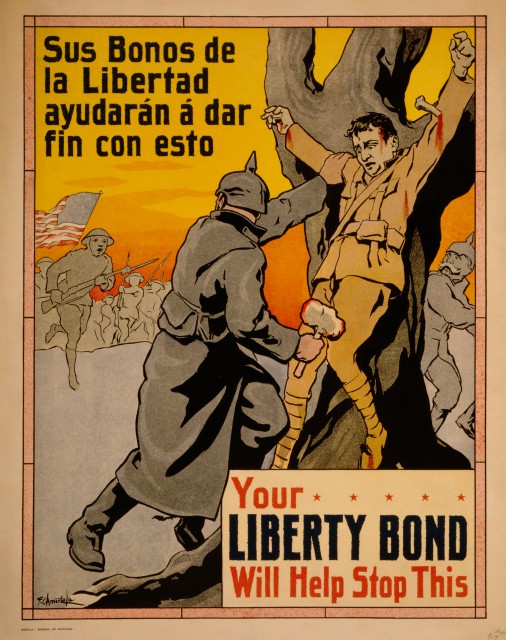

9. The Crucified Soldier

This is the story of an Allied soldier serving in the Canadian Corps that may have been crucified with bayonets on a barn door while fighting on the Western Front during World War I. The story refers to the widespread atrocity propaganda and is commonly known as the Crucified Soldier.

Around 24 April 1915 on the battlefield of Ypres, Belgium, three witnesses said they saw an unidentified crucified Canadian soldier, but there was no definite proof that such a crucifixion actually occurred.

The eyewitness explanations were rather contradictory, no body was found, and no pertinent information was uncovered at the time about the identity of the supposedly crucified soldier. During World War II the story was treated as an example of British propaganda by the Nazi regime.

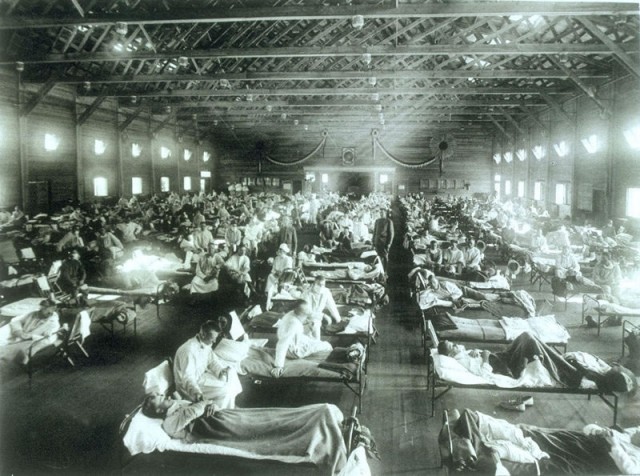

10. The Great Influenza Pandemic Killed More People than WWI

The 1918 influenza pandemic that lasted from January 1918 until December 1920 was an abnormally deadly influenza pandemic. 500 million people around the globe were infected, including remote islands in the Pacific and the Arctic Oceans.

Three to five percent of the earth’s population at the time died; 50 to 100 million people killed. It was one of the deadliest natural catastrophes in the history of mankind.

To maintain high morale, reports of sickness and death were minimized by wartime authorities in the Allied nations, but the newspapers were free to report the epidemic’s effects in neutral Spain.

The papers reported that Spain was especially hard hit and thus the pandemic’s nickname The Spanish Flu.