At the start of 1915, the Central Powers had high hopes for the Eastern Front. By launching massive attacks early in the year, they hoped to knock Russia out of the First World War, leaving them to focus their attention and resources on the war in the west.

Instead, they would suffer high costs for limited gains.

The German Offensive

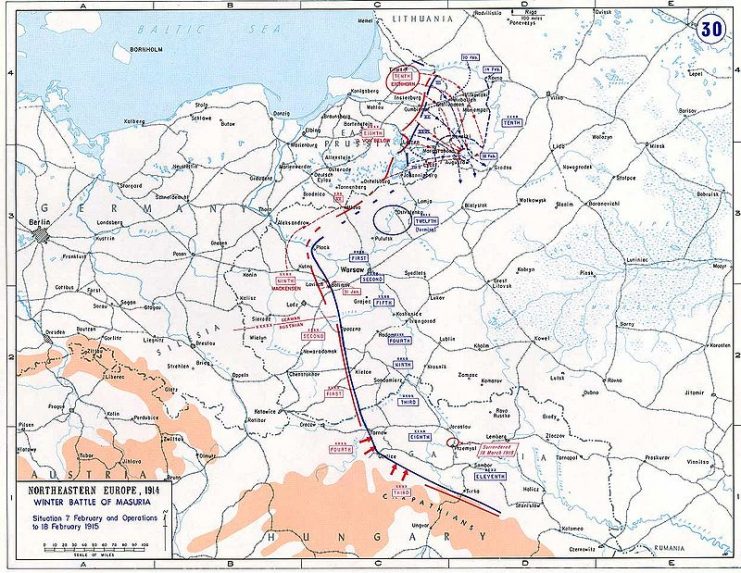

The offensive consisted of two prongs – one German, the other mixing German forces in with Austro-Hungarian armies.

The first prong began with a diversionary attack by the Ninth Army on the 31st of January. The army headed south-east out of East Prussia, marching towards Warsaw. This resulted in the Battle of Bolimov, a confrontation most notable for being one of the first where poison gas was used on the battlefield. The gas was ineffective, in large part because of the cold, and the battle was inconclusive.

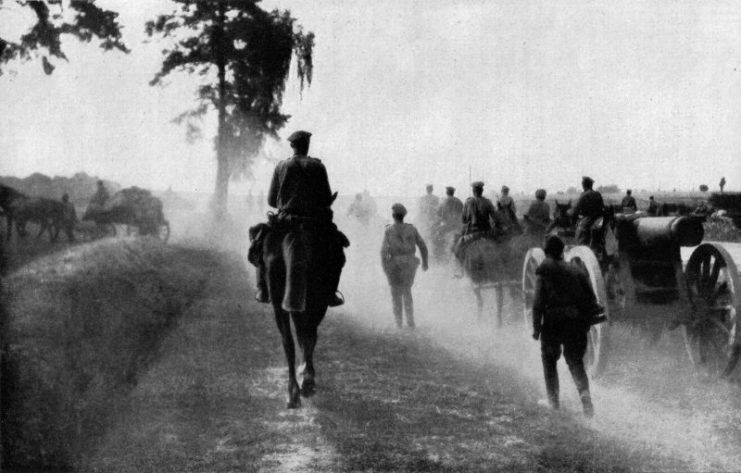

The main German thrust was launched on the 7th of February when the Eighth Army marched east out of East Prussia under the leadership of General Otto von Below. Advancing through a snowstorm, they approached the Russian Tenth Army. Isolated and caught in the flank, the Russians were defeated in the Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes.

On the 9th of February, the German Tenth Army under General Hermann von Eichhorn joined the fight. Advancing further south, they hit the Russian Tenth Army, which was already in a sorry state. The Russian army started to collapse, pulling back towards Kovno in the east.

Mixed Fortunes

These early successes provided a good omen for the Germans. They pressed on, driving the Russians before them.

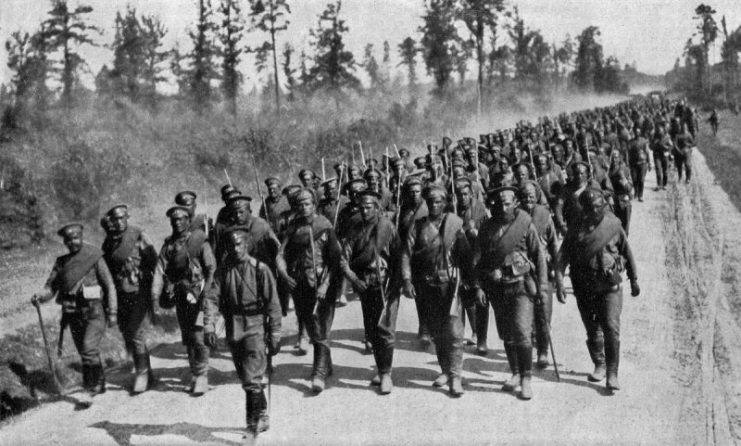

The speed of the retreat and the aggression of the German advance meant that three corps of the Russian Tenth Army were left behind, almost surrounded by enemy troops. One of these corps fought a rearguard action to buy the others time to escape. The desperate fight they put up held the German advance in the Augustovo Forest until the 21st of February.

The Germans had advanced far into Russian territory. Below’s Eighth Army had pushed the Russians back 60 miles in the first week alone. But the armies were starting to run out of steam, as exhaustion, casualties, and extended supply lines took their toll.

The Russians sent General Plehve and the Twelfth Army to deal with the faltering front. Their counter-attack finally stopped the German offensive. Having lost their advantage, the Germans fell back to the borders of East Prussia.

Despite a promising start, the Germans had gained little territory. Yet the outcome was also bleak for the Russians. Aside from having the weakness of their armies exposed, they had lost 200,000 men, 90,000 of them captured by the Germans and now held as prisoners of war.

The Austro-Hungarian Offensive

Further south, the second prong of the campaign had similarly mixed results.

This offensive was assembled in the Carpathian Mountains, the borderland between the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires. The Central Powers committed three armies to this advance. On the left was General Svetozar Boroevic von Bojna and the Austro-Hungarian Third Army. Next came the mixed Austrian and German South Army force, led by General Alexander von Linsingen. On the right was another Austro-Hungarian force, the Tenth Army under General Karl von Pflanzer-Baltin.

Von Linsingen’s army was assigned to make the main thrust. Heading north-east out of the mountains, they would drive towards Lemberg and relieve the fortress of Przemyśl to its west, which was currently under siege by the Russians. The commanders of the other two armies were instructed to support this maneuver.

The relief of Przemyśl was a symbolically as well as a strategically important operation. The fortress had been under siege almost constantly since the start of the war. The Austro-Hungarian press and public had taken an interest in its fate and it was now a cause that drew great attention. Any successful relief operation would draw public praise, while its fall would be a dispiriting moment for the nation.

As in the north, the campaign began well. The Austro-Hungarian Tenth Army reached Czernowitz and confronted the Russian Eighth Army under General Alexei Brusilov. The Austro-Hungarians defeated the Russians on the 17th of February, taking 60,000 enemy soldiers into captivity.

But the main thrust of the attack faired far worse. Winter was not a good time to move an army around Eastern Europe, and the South Army struggled to advance through the snowbound Carpathian Mountains. After several weeks, Przemyśl still lay out of reach.

Russia Counter-Attacks

The garrison at Przemyśl held out, hoping for the promised relief. But supplies were running low and they could only last so long. On the 22nd of March, the force of 120,000 men surrendered to the Russians.

Meanwhile, the Russians were preparing a series of local counter-attacks. These battered at the Austro-Hungarian and German forces for several weeks.

Then supply difficulties kicked in, the Russians finding themselves over-extended just as German troops under General Georg von der Marwitz arrived to reinforce the stalled South Army. The counter-attacks ended on the 10th of April.

The southern winter offensive had been a fiasco. The Austro-Hungarians suffered 800,000 casualties, most of them lost not to combat but to the weather. The army, already divided along ethnic lines, became fractious and demoralized. Calling in German support was a necessity to stop the front collapsing, but it did nothing to bolster the pride of the Austro-Hungarian army.

The winter offensive of 1915 had been a fine idea in principle. With more movement possible than in the west, the Eastern Front was the natural place to try to get a swift victory and reduce the war to a single front. But as so many leaders throughout history learned, an invasion of Russia in winter was never going to be swift or easy.